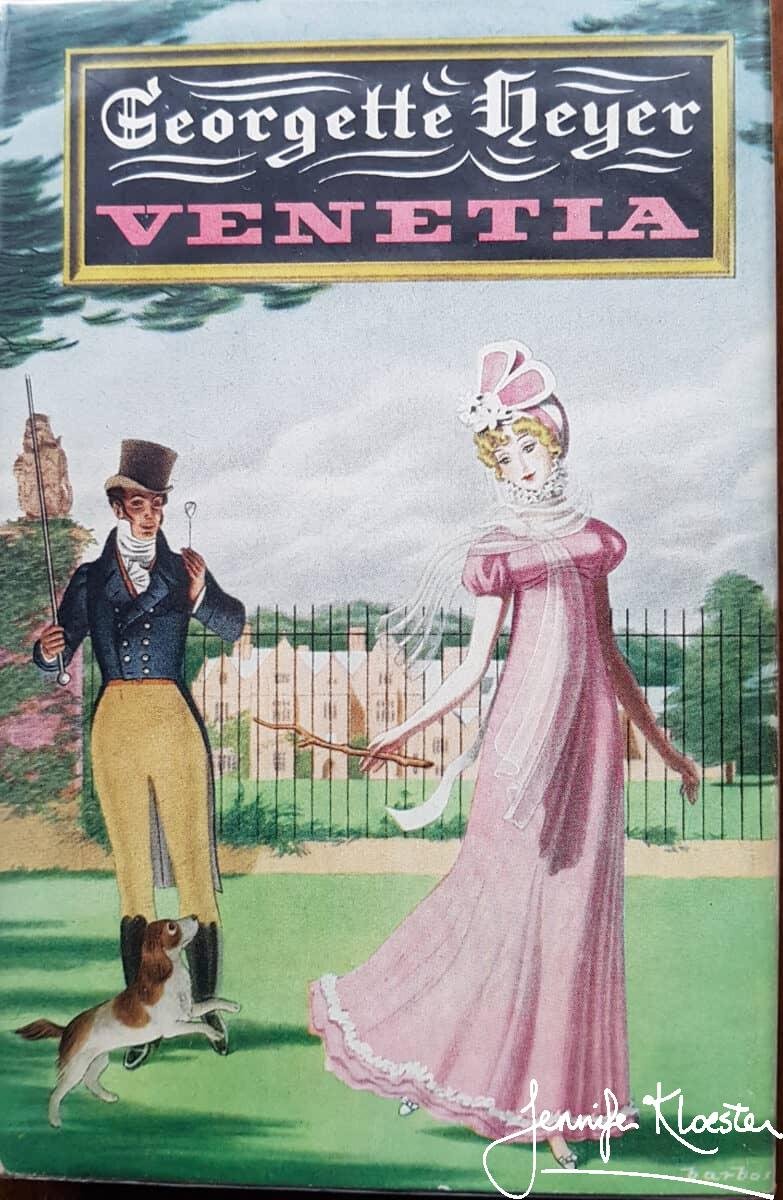

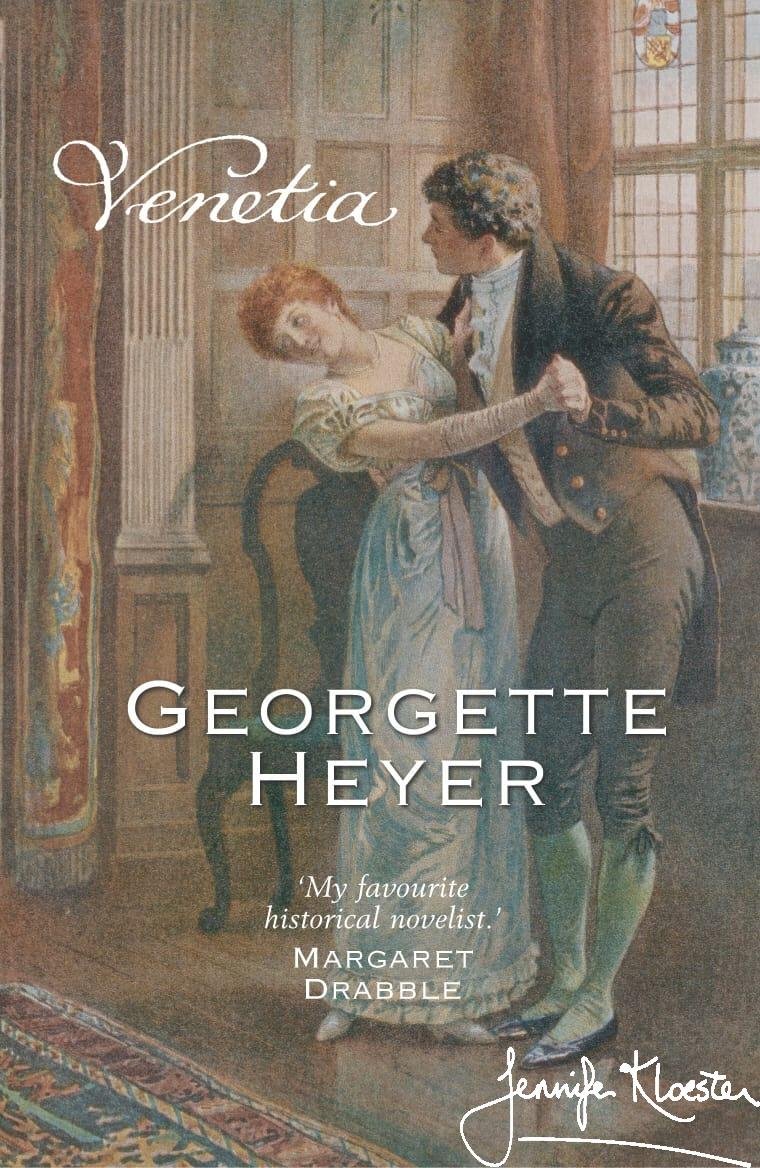

It may not be quite like Me, but I’m pretty sure the fans will like it.

Georgette Heyer to AS Frere, letter, 7 March 1958

Georgette Heyer’s Venetia (1958) is Heyer’s most complex, literary, and also physically sensuous and emotional work

Anne Lancashire, “Venetia: Georgette Heyer’s Pastoral Romance, JPRS, 22 December 2020

A sparkling tale

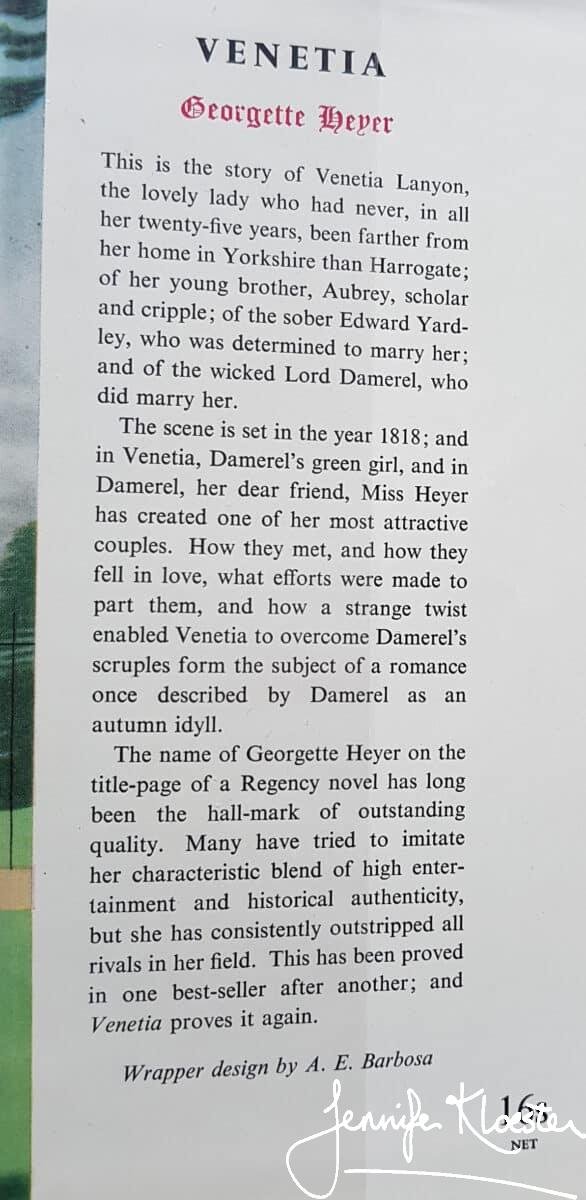

Venetia would be Georgette Heyer’s 17th Regency novel and also one of her finest books. It is a remarkable reflection of her enduring talent that more than forty years after writing her first novel, her forty-sixth book should be so fresh and new. Venetia is a sparkling tale of newfound love, idyllic romance, and friendship. It is also a novel about selfishness, a book about honesty and, as Anne Lancashire, explains in her excellent article, “Venetia: Georgette Heyer’s Pastoral Romance”, it is a story that draws on the long tradition of the pastoral – the centuries-old literary genre that “celebrates, with stylistic artifice, rural life as an idyllic escape from the burdens and anxieties of everyday existence in a non-rural environment”. As Lancaster points out, Venetia belongs to the sub-genre of pastoral romance, with its beautiful heroine, whose life, lived for so long in her pleasant rural fastness, is interrupted by the arrival of the hero from the outside world. Heyer’s hero is the much-beloved, Lord Damerel, a rake with a past who enters into the romantic rural idyll of Undershaw and wins Venetia’s love, only to retreat when he decides he cannot give her the life he believes she deserves.

“The typical pastoral romance, as seen, with variations, in Shakespeare’s plays and most clearly in Book VI of The Faerie Queene, thus has an active hero from a courtly (i.e., socially-developed) environment who retreats, distracted or wounded in body or in spirit, into an idyllic countryside – an Arcadia – where the sun always shines, the shepherds and shepherdesses or their narrative equivalents live and love without undue labour or anxiety, and every day is holiday-like. For a while the hero remains, enjoying the pastoral environment. Inevitably part of his experience involves a romance with a beautiful shepherdess or equivalent, who prefers him to less-accomplished rural swain(s). Eventually a disruptive force from the outside world (e.g., bandits in The Faerie Queene, the hero’s father in The Winter’s Tale, news of death in Love’s Labor’s Lost) breaks into the idyllic pastoral world, and the hero realizes that no permanent retreat from the complications of life is possible or desirable. He returns, renewed and strengthened by his pastoral experience, to responsible action in the active social world from which he came, either leaving behind him the beautiful shepherdess or, as in Book 6 of The Faerie Queene and The Winter’s Tale, taking her with him and discovering later that she is in fact no shepherdess but a member of his own social class, who was abandoned or hidden in the pastoral world as an infant, and so has now been appropriately brought back by him to the non-pastoral world to which they both belong.”

Anne Lancashire, “Venetia: Georgette Heyer’s Pastoral Romance”, in Journal of Popular Romance Studies, 22 December 2020

Damerel

There is so much to love about Venetia, but one of the novel’s greatest attractions is Jasper, Lord Damerel. Described by Heyer as “dark, his countenance lean and rather swarthy, marked with lines of dissipation” he also carries himself with “a faint suggestion of swashbuckling arrogance”. Venetia has never yet met him but years earlier she has dubbed him “the Wicked Baron” due to his reputation for rakehell living. As a young man Damerel fell in love and ran off with a married woman and was subsequently cast off by his family. Since then his reputation has not improved. Months before the story begins, Damerel has confirmed society’s view of him and scandalised the neighbourhood by bringing a party of “rackety-bucks” and three females well known to be “lightskirts” to his home at The Priory for a week spent indulging in “vulgar rompings” and “orgies”. Venetia first meets Damerel while she is out picking blackberries on his property which runs alongside her home at Undershaw. He mistakes her for a village maid and ruthlessly kisses her. Venetia is furious and responds to his earlier quotations about her beauty with one of her own. Quoting Othello she calls Damerel “a pestilent, complete knave”. He immediately recognises the quotation and his mistake in thinking her lower down the social scale than himself. Realising that she is well-bred and literate as well as beautiful, he is instantly intrigued. Among the many things that attract Damerel to Venetia it is her honesty or “plain-speaking” that sets her apart from other women. Heyer brilliantly depicts the moment when Damerel first becomes aware that Venetia is unlike other females. After her brother Aubrey has fallen from his horse and been rescued by Damerel, the wicked Baron writes to her in “a spirit of unholy amusement” that he believes will bring her to the Priory in a state of perturbation and even resentment. He looks forward to soothing her “ruffled plumage” and is not only taken aback but utterly smitten when she arrives instead in a “glow of warm gratitude”. This interlude marks the beginning of their real relationship – the moment when Damerel discovers that Venetia is a being outside his experience and one with whom he must begin his friendship on fresh terms.

Honesty

The scene in which Damerel and Venetia meet sets the tone for the rest of the book. This is a novel full of classical allusions and Georgette’s hero and heroine regularly use quotations in their conversations with each other. There are so many layers in Venetia (one could write a book about the cleverness of the novel!) and the use of quotations is but one marker of them. Not only are the lines from Shakespeare, Pope’s or Campion’s poetry or references to the Greek plays of Sophocles and Euripides apposite when used as dialogue between Venetia and Damerel, but the use of these words also show that this is a meeting of like minds. Damerel and Venetia are perfect for each other: they speak the same language, they have a similar sense of humour, they are each honest in their speech and (and Damerel for the most part) in their emotions. Venetia as a novel has much to say about honesty. Venetia is no dissembler and to speak honestly and without an ulterior motive is her natural state. This theme plays out through the course of the book and makes Venetia one of Georgette’s most endearing heroines. Venetia herself has what we would call today “High EQ” – in that is she is very emotionally intelligent. From the opening scene, where she teases her brother, Aubrey, we learn from Heyer’s subtle prose how well Venetia understands the men in her life and how she sees and accepts their innate selfishness. Having been, like the sleeping beauty she is likened to towards the end of the novel, held at Undershaw for most of her life, she has come to accept her loneliness and thwarts ambition as her lot in life. Venetia’s situation forces her to consider deeply whether she should accept her very dull, pompous and irritating – though “worthy” – suitor, Edward Yardley’s proposal of marriage. It is not what she wants, but what she fears must be, else she becomes no more than an aunt to her brother Conway’s children.

‘Marriage to Edward would be safe and comfortable. He would be a kind husband, and he would certainly shield her from inclement winds. But Venetia had been born with a zest for life unknown to him, and a high courage that enabled her to look hazards in the face and not shrink from encountering them. Because she did not repine over her enforced seclusion Edward believed her to be content, as he himself was content, to pass all her days under the shadow of the Cleveden Hills. So far from being content she had never imagined that this could be her ultimate destiny. She wanted to see what the rest of the world was like: marriage only interested her as the sole means of escape for a gently-born maiden.’

Georgette Heyer, Venetia, Pan, 1979, p.27.

Venetia’s honesty is total. In both her inner life and in her external world she recognises and speaks truth. It is this that most endears her to Damerel and this that enables her, when the chance finally comes, to seize life with both hands. By the end of the novel, it is Venetia’s innate honesty that inverts the traditional ending to the pastoral romance and gives her the happiness she deserves and for which she has fought so hard.

The ghastly Mrs Scorrier

Venetia is a book driven by character rather than plot and Georgette brought to life her dramatis personae with extraordinary dexterity. Even her stock characters: old nurse, the pompous young man, the naïve young wife and her dreadful, vulgar mother are rendered anew in Venetia. The ghastly Mrs Scorrier, in particular, reflects Heyer’s skill in depicting characters that are true to life and who are so real that they evoke a visceral reaction in the reader. Coming en scene at the midpoint of the novel, Mrs Scorrier is one of Georgette’s Austen-inspired characters – a descendant of Mrs Norris – and a woman we love to loathe. Her officiousness, her dictatorial nature and her habit of putting people offside are all superbly rendered and it is Damerel who reveals his perspicacity and most succinctly sums her up:

‘One of the advantages of having led a sequestered life,’ said Damerel, smiling, ‘is that you’ve not until now encountered the sort of woman who can’t refrain from quarrelling with all who cross her path. She is forever suffering slights, and is so unfortunate as to make friends only with such ill-natured persons as soon or late treat her abominably! No quarrel is ever of her seeking; she is the most amiable of created beings, and the most long-suffering. It is her confiding disposition which renders her prey to the malevolent, who, from no cause whatsoever, invariably impose upon her, or offer her such intolerable insult that she is obliged to cut the connexion.’

Georgette Heyer, Venetia, Pan, 1979, p.183.

“A promising idea for a new book”

“I think I have a fairly promising idea for the next book. A short one, I fancy, and not a lot of plot, but I like my heroine, and I think the hero should please the fans. I hope to get it exactly mapped out over the week-end, and if I can succeed in this I’ll let you know broadly what this story is about, and what I am calling it. I’d like to call it Venetia, since that is the heroine’s name, but believe it would be unwise, as leading the more erudite to expect a book about Venetia Stanley.”

Georgette Heyer, letter to AS Frere, 11 January 1958

Venetia Stanley Montagu was a “collateral descendant” of Venetia Stanley’s

Venetia Stanley (later Digby) who inspired Georgette Heyer to write Venetia. Painted by Peter Oliver in the 1600s

Two Venetias

The Venetia Stanley to whom Georgette was referring was a woman only fifteen years her senior. Born in 1887, Beatrice Venetia Stanley Montagu was a British aristocrat and famous socialite. She was notable for her correspondence, between 1910 and 1915, with the British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. Asquith adored women and in just three years he wrote over 500 letters to Venetia. They became very close, though whether the relationship was ever sexual is unclear. Asquith was Prime Minister for eight of Georgette’s most formative years (1908-1916) and Venetia Stanley was a well-known figure during her teen years and young adulthood. Venetia Stanley was also a collateral descendant of the Venetia who inspired Heyer’s superb 1958 novel of the same name.

The original Venetia Stanley was born in 1600 and became one of Stuart society’s most acclaimed beauties. In the spring of 1625 she secretly married Kenelm Digby and in October bore him a son, also Kenelm. Her husband did not acknowledge the marriage until 1627 but the couple went on to have two more sons, before Venetia’s untimely death in 1633. Georgette knew of the earlier Venetia from the poems written at the time of Venetia’s death in 1633. Ben Johnson, Aurelian Townsend, Thomas May, William Habington, and Owen Feltham all commemorated Venetia Digby’s untimely demise in verse. Georgette, like her father, George Heyer, – indeed, because of him – was an avid reader of the Renaissance poets and she was familiar with Venetia’s story. Today Heyer’s copy of Aubrey’s Brief Lives still sits among the remnant of her library and she may also have acquired a copy of Oliver Lawson Dick’s, Aubrey’s Brief Lives, published in 1949. This acclaimed book was also (coincidentally) republished in 1958, the same year that Georgette’s Venetia appeared. Lawson had compiled a complete set of John Aubrey’s often impudent, intimate pen sketches from Aubrey’s original 17th-century manuscripts. Among the collection’s many short biographies, is one describing Venetia Stanley:

“Venetia Stanley was the daughter of Sir Edward Stanley. She was a most beautifull desireable Creature, and being maturo vivo was left by her father to live with a tenant and servants at Enston Abbey in Oxfordshire: but as private as that place was, it seems her Beautie could not lye hid. The young Eagles had espied her, and she was sanguin and tractable, and of much Suavity (which to abuse was great pittie).

John Aubrey, Aubrey’s Brief Lives, edited by Oliver Lawson Dick, Secker & Warburg, London, 1958.

Sir Kenelm Digby by Sir Anthony Van Dyck (Wikimedia Commons)

Venetia Digby by Sir Anthony Van Dyck (Wikimedia Commons)

Inspiration

‘You may think this frivolous of me, but have you ever read what Aubrey said of Venetia? “A beautiful, desirable creature” Also, “about the eyelids great sweetness.” Well, you see what I mean? But Johnson has one or two nice phrases, & I think I may find something in Aurelian Townsend, & Habington, both of whom wrote poems to her. My hero, I should add, is rather given to quotation.’

Georgette Heyer to AS Frere, letter, 7 March 1958

Aubrey’s portrait of this first Venetia is short – only two pages – but it was more than enough to inspire Georgette with its marvellous description of the original Venetia. Her own heroine would also be beautiful and like her namesake would be left by her father to live all-too privately in the family estate of Undershaw in the Yorkshire countryside. Heyer named her heroine’s brother “Aubrey” in tribute to the seventeenth-century biographer, and she would name Venetia’s mother, “Aurelia” in tribute to one of the poets who wrote so feelingly about Venetia Digby. Having told her publisher, A.S. Frere that ‘I never do my most sparkling stuff when labouring under adversity’, Georgette proceeded to produce in Venetia one of her finest novels. It is in many ways a quiet book, with a great deal of subtle humour and layer upon layer of deeper meaning. At one point, Georgette described the novel as ‘not quite like Me’ when in fact it was simply one of several novels that marked the apogee of her writing career. She told Frere that it was not ‘an adventurous novel’ nor one with ‘any movement in it worth mentioning’, but in her own, typically understated way, she recognised its merits and hoped that others would too:

‘I wonder very much what you’ll think of it. I’m damned if I know what I think. I haven’t quite read it through, but what I have read seemed to me not at all bad. There’s even some rather good stuff in it! Ronald seems to like it, & is kind enough to say that he doesn’t think it’s a bad thing that it’s rather different from my usual froth.’

Georgette Heyer to AS Frere, 9 May 1958

Once again she waited in vain for her publisher to read her work and respond.

Aurelian Townshend – Venetia

An Elegie Made by Mr. Aurelian Townshend in Remembrance of the Ladie Venetia Digby, by Aurelian Townshend What Travellers of matchlesse Venice say, Is true of thee, admir'd Venetia; Hee that ner'e saw thee, wants beliefe to reach Halfe those perfections, thy first sight would teach. Imagination can noe shape create Airy enough thy forme to imitate; Nor bedds of Roses, Damask, red, and white, Render like thee a sweetnes to the sight. Thou wer't eye-Musike, and no single part, But beauties concert; Not one onely dart, But loves whole quiver; no provinciall face, But universall; Best in every place. Thow wert not borne, as other women be, To need the help of heightning Poesie, But to make Poets. Hee, that could present Thee like thy glasse, were superexcellent. Witnesse that Pen which, prompted by thy parts Of minde and bodie, caught as many heartes With every line, as thou with every looke; Which wee conceive was both his baite and hooke. His Stile before, though it were perfect steele, Strong, smooth, and sharp, and so could make us feele His love or anger, Witneses agree, Could not attract, till it was toucht by thee. Magneticke then, Hee was for heighth of style Suppos'd in heaven; And so he was, the while He sate and drewe thy beauties by the life, Visible Angell, both as maide and wife. In which estate thou did'st so little stay, Thy noone and morning made but halfe a day; Or halfe a yeare, or halfe of such an age As thy complexion sweetly did presage, An houre before those cheerfull beames were sett, Made all men loosers, to paye Natures debt; And him the greatest, that had most to doe, Thy friend, companion, and copartner too, Whose head since hanging on his pensive brest Makes him looke just like one had bin possest Of the whole world, and now hath lost it all. Doctors to Cordialls, freinds to counsel fall. He that all med'cines can exactly make, And freely give them, wanting power to take, Sitts and such Doses howerly doth dispense, A man unlearn'd may rise a Doctor thence. I that delight most in unusuall waies, Seeke to asswage his sorrowe with thy praise, Which if at first it swell him up with greife, At last may drawe, and minister releife; Or at the least, attempting it, expresse For an old debt a freindly thanckfulnesse. I am no Herald! So ye can expect From me no Crests or Scutcheons, that reflect With brave Memorialls on her great Allyes; Out of my reach that tree would quickly rise. I onely stryve to doe her Fame som Right, And walke her Mourner, in this Black and Whight.

Ben Johnson – Venetia

XXVI. Melancholy From ‘Elegy on the Lady Venetia Digby’ By Ben Jonson (1572–1637) ’TWERE time that I died too, now she is dead, Who was my Muse, and life of all I said; The spirit that I wrote with, and conceived All that was good or great, in me she weaved…. Thou hast no more blows, Fate, to drive at one: What ’s left a poet, when his Muse is gone?… Indeed, she is not dead! but laid to sleep In earth, till the last trump awake the sheep And goats together, whither they must come To hear their Judge, and His eternal doom…. And she doth know, out of the shade of death, What ’tis to enjoy an everlasting breath! To have her captived spirit freed from flesh, And on her innocence, a garment fresh And white, as that, put on: and in her hand With boughs of palm, a crownèd victrice stand!… She was in one a many parts of life; A tender mother, a discreeter wife, A solemn mistress, and so good a friend, So charitable, to religious end In all her petite actions, so devote, As her whole life was now become one note Of piety, and private holiness. She spent more time in tears herself to dress For her devotions, and those sad essays Of sorrow, than all pomp of gaudy days; And came forth ever cheered, with the rod Of divine comfort, when she had talked with God.