Georgette Heyer did not publish a book in 1945. She had been remarkably prolific throughout the 1930s with sixteen published titles in that decade alone. The 1940s, however, would prove to be a decade of change. Although she still managed to publish nine novels between 1940 and 1949, Heyer did not produce a book at all in either 1943, 1945 or 1947. There are several likely reasons for these unusual (for her) gaps in her writing. Illness, war, family demands and a severe paper shortage were all factors, but Georgette was also progressing into middle age and finding it harder to summon the extraordinary energy that had enabled her to write an average of two books a year between 1928 and 1941. It is also perhaps unsurprising that there was no new Georgette Heyer novel in 1945 given that in May of that year the Second World War ended and in September her only child, Richard, began the next stage of his education as a boarder at Marlborough College. The first intimation of a new novel came soon after Georgette had seen Richard off to his new school. She wrote to her friend and publisher at Heinemann, A.S. Frere, to tell him that:

‘There is a book going round in my own head like a borer beetle, but it hasn’t yet chrystalised. Do you like mixed metaphors?’

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 30 September 1945.

A delightful parody of the Gothic romance

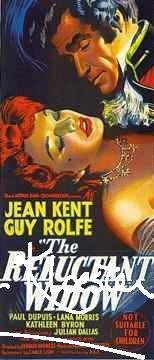

The book eventually did ‘chrystalise’ and Georgette was soon once again engrossed in writing her new novel. Another Regency historical, this was to be a delightful parody of the Gothic romance and a book which offered its author plenty of scope for her comic talents. Georgette had grown up reading many of the classics including Jane Austen who was her favourite author. Austen’s novel Northanger Abbey is a clever and humorous parody of the Gothic novels popular in her day and Heyer obviously took pleasure in writing her own humorous Gothic tale. The novel – eventually to be called The Reluctant Widow – has a compelling and suitably sinister opening. Miss Elinor Rochdale, well-born but penniless and alone in the world, alights from a stagecoach with the expectation of being met by a servant in a gig and transported to her new home, there to work as governess to one Mrs Macclesfield’s ‘high-spriited’ (read difficult) seven-year-old son. When approached by a servant and asked if she is the young lady ‘come down from London in answer to the advertisement’, Elinor agrees and is soon on her way (in an unexpectedly luxurious carriage) to her new home. But all is not as it seems and the house to which she is taken is gloomy and decayed. She is led to the library and there meets the man she assumes to be her employer. A conversation ensues and it is some time before Elinor discovers that she and the man before her have been talking at cross-purposes. Aghast to find herself in the wrong house, she demands to be taken to Mrs Macclesfield’s. Unfortunately, it is by now past a respectable hour for arrival and Lord Carlyon is now bent on persuading Elinor to aid him in a truly Gothic plan. It is Carlyon’s wish that she marry his young and dissolute cousin, Eustace! All of this transpires in chapter one and such is Heyer’s skill that the reader (and Elinor) are not only convinced but amused by the reasons for Carlyon’s Machiavellian machinations.

‘Gothic shenanigans’ and a rare error

Georgette had great fun creating a suitably Gothic setting for her heroine, the newly wed and newly widowed, Elinor Rochdale – now Mrs Cheviot. Highnoons, the house she inherits from her deceased husband, has long been neglected and its overgrown garden, vine-clad windows, dusty rooms and skeleton staff prompt her heroine to make reference to ‘all of one’s favourite romances’. Heyer, of course, had read the most famous early Gothic novelists such as Clara Reeve, Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe and Monk Lewis and she uses elements of their work such as secret passages, attacks in the night, locked rooms, and foreign conspirators to good effect in The Reluctant Widow. Heyer does make one rare and surprising mistake in the novel, however. when she describes Elinor reading a novel on her first evening at Highnoons. Initially described as a book by ‘Miss Clara Reeve’s story’ Heyer goes on to describe Elinor’s reaction to ‘Orlando and Monimia’s’ melodramatic story. But their story was by Miss Charlotte Smith who published The Old Manor House in 1793. Later in the scene, Heyer does refer to ‘Miss Smith’s Monimia’, so she clearly knew who the author was but accidentally inserted Clara Reeve’s name instead of Charlotte Smith’s at the beginning. Despite this minor error, The Reluctant Widow is replete with the tropes and clichés of the Gothic romance. Elinor, too, is familiar with the Gothic tradition and able to observe to Lord Carlyon in a humorously sarcastic comment that:

‘I hope there may be a blasted oak. I do not ask if a spectre walks the passages with a head under its arm: that would be a great piece of folly! …The house is clearly haunted. I have not the least doubt that that is why only two sinister retainers can be brought to remain in it. I dare say I shall be found, after a night spent within these walls, a witless wreck whom you will be obliged to convey to Bedlam without more ado.’

Georgette Heyer, The Reluctant Widow, Pan, 1961, p.75.

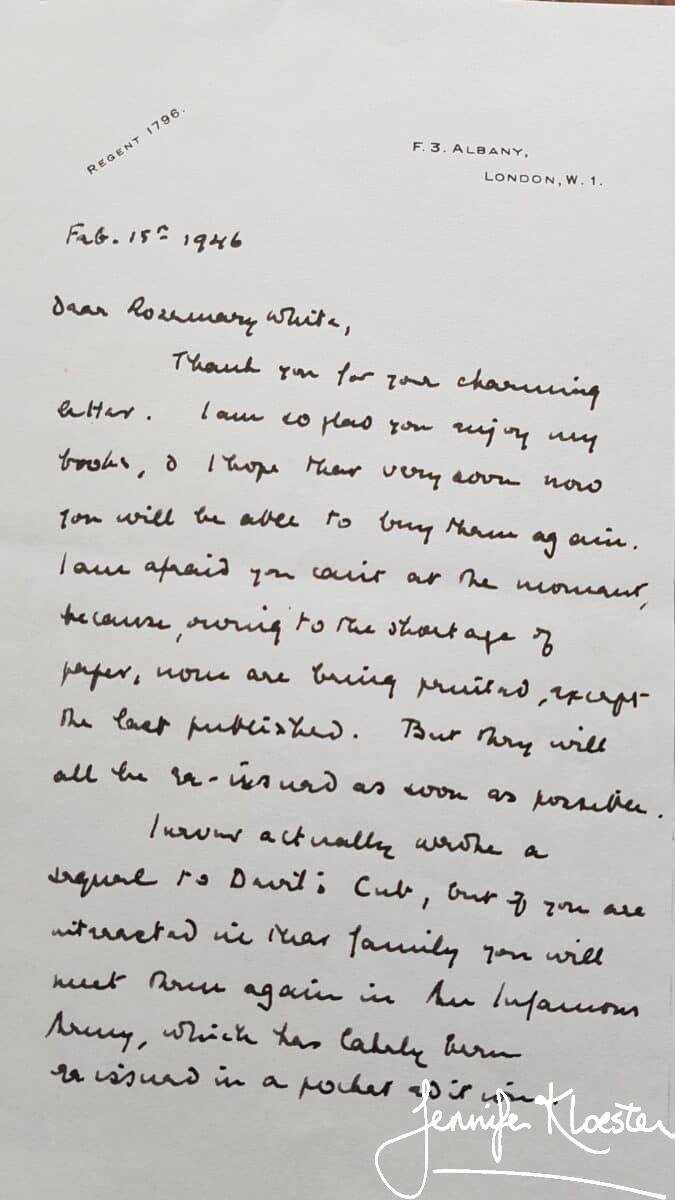

‘I expect you will like my new book’

In February 1946, Georgette wrote to a young Australian fan to say that her novel, The Reluctant Widow, would be published in the spring. Knowing teenage Rosemary to be an avid reader of her novels, Georgette said, ‘I expect you will like my next novel’ and went on to thank her for the parcel of food which Rosemary and her mother had sent Georgette from Australia. While Georgette Heyer had a reputation for disliking her fans this was not entirely true. What she disliked were people who gushed over her novels, describing them as ‘sweetly pretty’ or demanded to know ‘where she got her ideas?’. Georgette loved people reading her books and she always answered fan mail that she thought sensible or intelligent, but she was impatient of readers who flattered her or suggested (as one reader did) that a statue be erected in Georgette’s honour. When young Rosemary White from Shepparton in Victoria, Australia, wrote to Georgette out of concern for her well-being on account of the strict food rationing in Engand after the War, her favourite author could not help but be touched. Worried that Georgette might be starving and (unsurprisingly) oblivious to her real circumstances – Georgette was living in Albany and shopping for food at Fortnum & Mason’s and Harrods – for several years Rosemary and her mother sent Georgette and her family food parcels. Each year a parcel would arrive at Albany with a large homemade fruit cake and packets of dried fruit and nuts and Georgette would respond by writing her young admirer pleasant, chatty letters and sending her signed copies of her latest novel. There was much in The Reluctant Widow for Rosemary to love for Georgette had given the hero an endearing younger brother, Nicky, who was guaranteed to win the heart of a romantic teenager. Georgette’s own son, Richard, was fourteen when The Reluctant Widow was published and there is no doubt that he influenced her creation of Nicholas Carlyon.

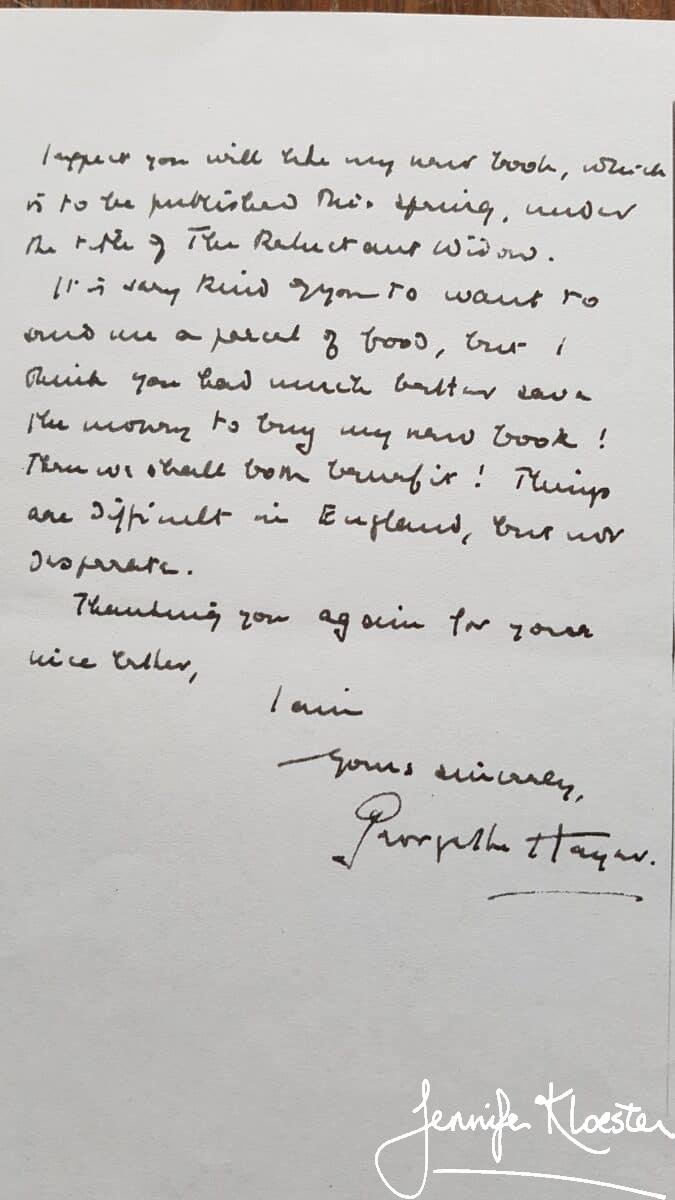

The first (but hopefully not the last) Heyer movie

‘Miss Wallace tells me that there is a whisper down the chromium and three-ply corridors of what is called the film industry, that Somebody Wants THE RELUCTANT WIDOW.’

Frere to Georgette Heyer, letter, 2 April 1946.

And indeed somebody did. It took another four years but in 1950The Reluctant Widow (The Inheritance in the USA) finally made it to the big screen. Georgette had long wanted her books made into films. From as early as 1925, when she had urged her agent, Leonard Moore, to try and sell a film option for Simon the Coldheart, she had yearned to see the product of her imagination on the silver screen. In 1935 she wished that someone would see ‘what a super film Regency Buck would make’ and in the 1960s she was delighted when Anna Neagle became interested in playing Lady Denville in a film of False Colours. In 1971 she actually sold the film rights to These Old Shades. Sadly, so far, nothing has come of the many options sold to various production companies for a film or series of Georgette Heyer’s wonderful novels. I do not despair, however, for the books are ripe for production into a well-crafted, witty and intelligent film or television series and in many ways this seems more likely now than ever before. The 1950 production of The Reluctant Widow was not a box-office hit but then it diverged so far from Heyer’s clever comic novel that that is probably not surprising. While perfectly watchable (you can see it here) with some fine scenes and a charming opening with a stage-coach, it does not come close to doing Georgette justice. She never saw the film, mainly because her son Richard saw it and was appalled by it. He told his mother ‘don’t go, Mummy, You would hate it’. In fact, the final film is not that bad (for an excellent account of it see Rachel Hyland’s essay in Heyer Society), but Georgette was put off by the advance publicity which she found too salacious:

‘I am being driven frantic by the advance publicity from Durham, and am trying to think what I can do about it. I feel as though a slug had crawled over me. I think it is going to do me a great deal of harm, on account of the schoolgirl public. Already I’m getting letters reproaching me. They have turned the Widow into a “bad-girl” part for Jean Kent, and this week’s Illustrated carries two pages, headed “Jean Locks Her Bedroom Door”. Also seduction scenes 1 and 2. If you can think of any answer, for God’s sake tell me! Smith, of Christy & Moore, is going to try to go down to see the rushes, and hopes we may be able to do something through diplomacy. I don’t think there’s much hope. I should like a notice to appear in every paper disclaiming all responsibility. At all events, I think I can get my name removed from the thing, and I shall. It seems to me that to turn a perfectly clean story of mine into a piece of sex-muck is bad faith, and something very different from the additions and alterations one would expect to be obliged to suffer. If I had wanted a reputation for salacious novels I could have got it easily enough. The whole thing is so upsetting that it is putting me right off the stroke.’

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, 30 November 1949.

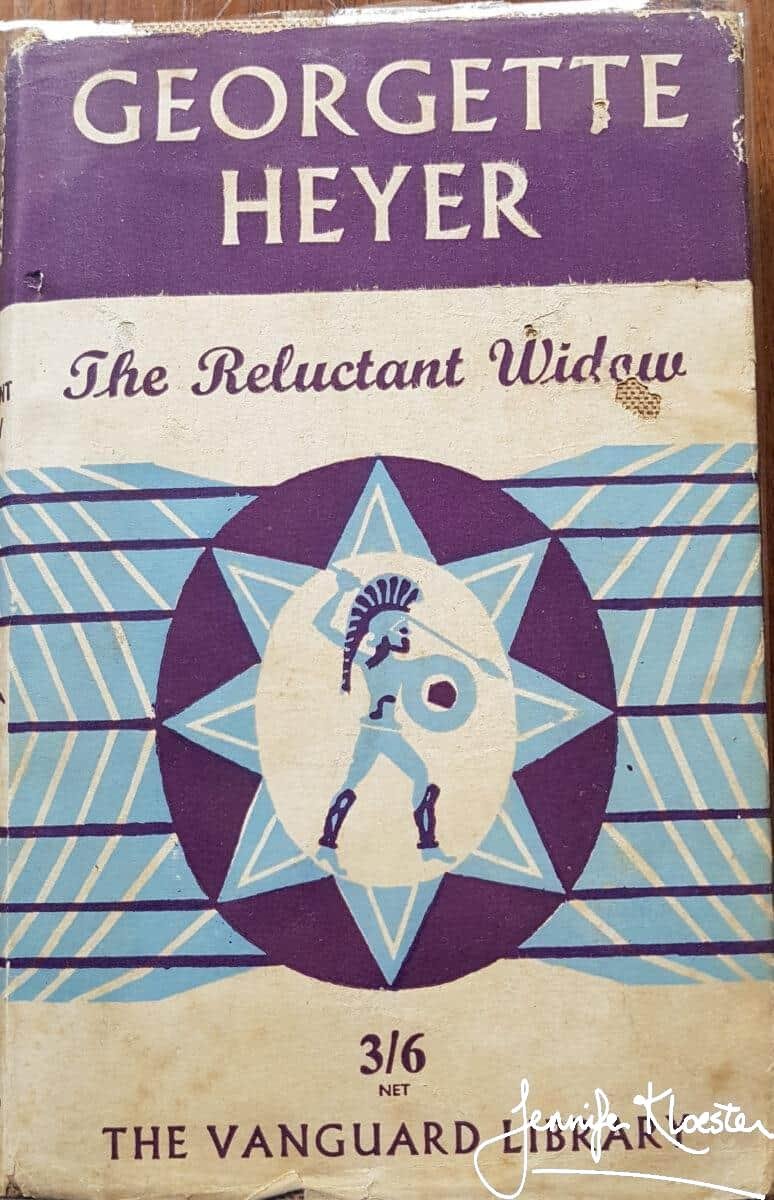

Valued and esteemed

It is a pity that the film of The Reluctant Widow did not do the book justice, especially as Georgette’s novels were so highly valued and esteemed by her publisher and her readers. In 1952, Heinemann in association with Chatto & Windus published a limited series for its ‘Vanguard Library’. The first author to be included in this series was Somerset Maugham, followed by Aldous Huxley, Graham Greene and Compton Mackenzie. Daphne du Maurier was fifth and Georgette Heyer was the seventh author to be added to the list. Heyer’s inclusion re-emphasises the way she was perceived during her lifetime – as a writer who appealed to people across the social and cultural spectrum. While her appeal has not lessened and she is well on the way to becoming a classic author, it is unfortunate that, as Stephen Fry recently pointed out, the covers of her books do not always reflect the wit, the humour and the intelligence of their contents.

Countless comic moments

A light-hearted story with countless comic moments, The Reluctant Widow is also a murder mystery with two deaths and a denouement in which the spotlight is captured by one of Georgette’s most deceptively ruthless and yet utterly debonair characters: the dandy Francis Cheviot. The happy ending is assured, however, and nearly fifteen years later Ronald was forcibly reminded of it in court. In February 1959, at a session of the Water Bill Committee Hearings in the House of Commons (in which Ronald was acting as counsel for the Committee), the Chairman, Major Legge-Bourke, made a speech to the opposing counsel:

The Chairman: Perhaps I might say to you, Lord Vaughan, that while you were using the wedding-metaphors I could not help but be reminded of something with which Mr Rougier is, perhaps, more familiar, from The Reluctant Widow, by Georgette Heyer: “I have spent a great deal of my life listening patiently to much folly. In my sisters I can support it with tolerable equanimity. In you I neither can nor will. Will you accept my hand in marriage, or will you not?”

Lord Vaughan: Mr Rougier has matrimonially the advantage!

House of Commons: Minutes of Evidence taken before the Committee on Group B of Private Bills on the South Bucks & Oxfordshire Water Bill, Bucks. Water Bill, Readings Berkshire Gate Bill, Mid-Wessex Water Bill, Wednesday 4th February 1959.

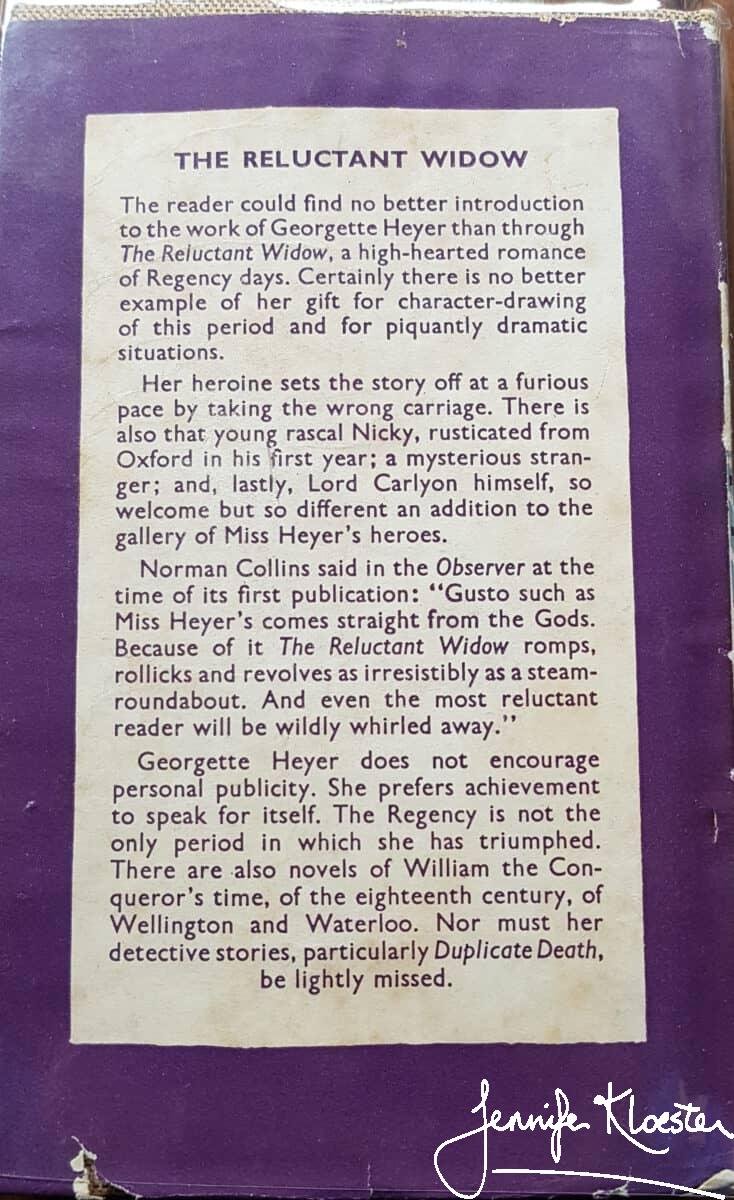

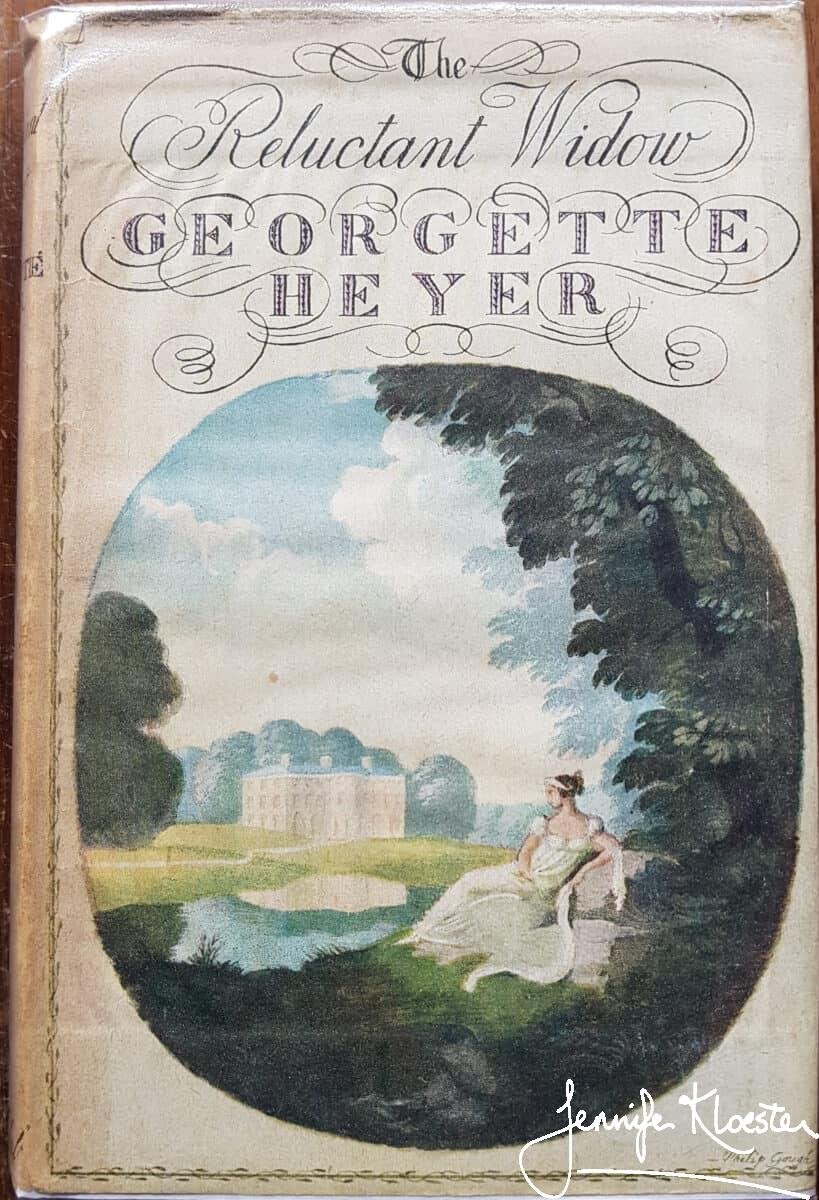

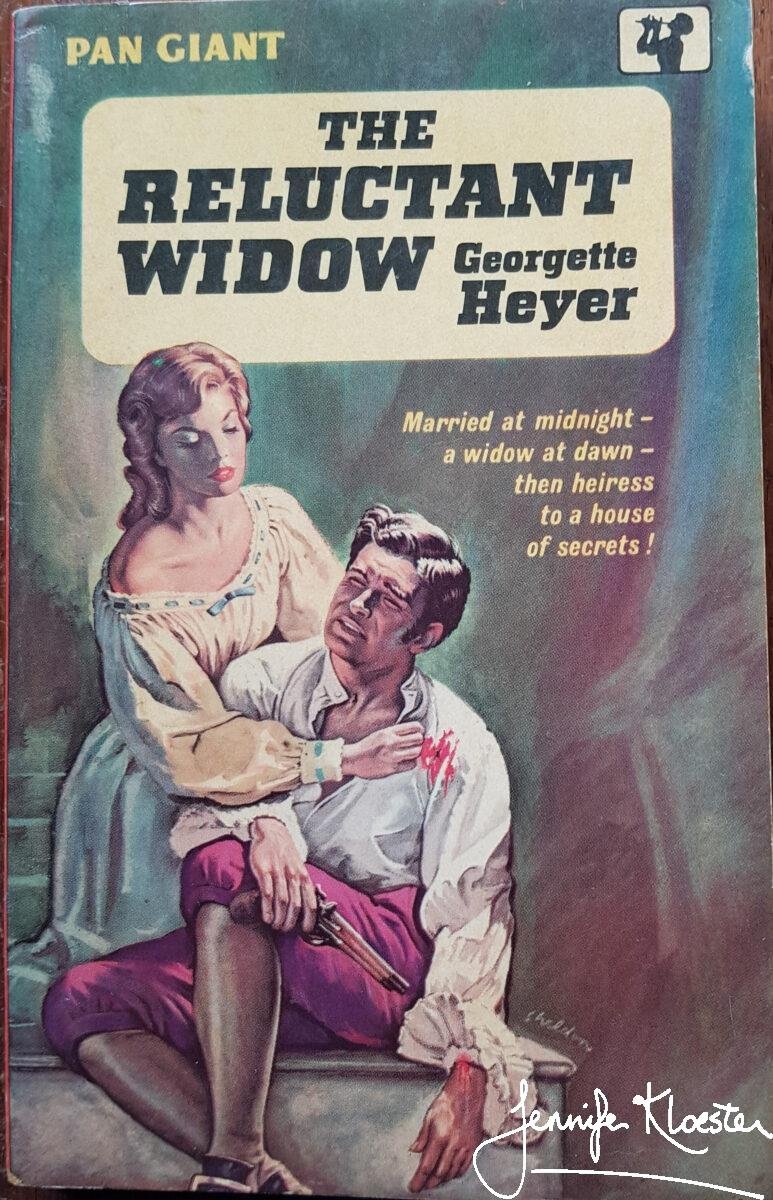

The 1961 Pan edition

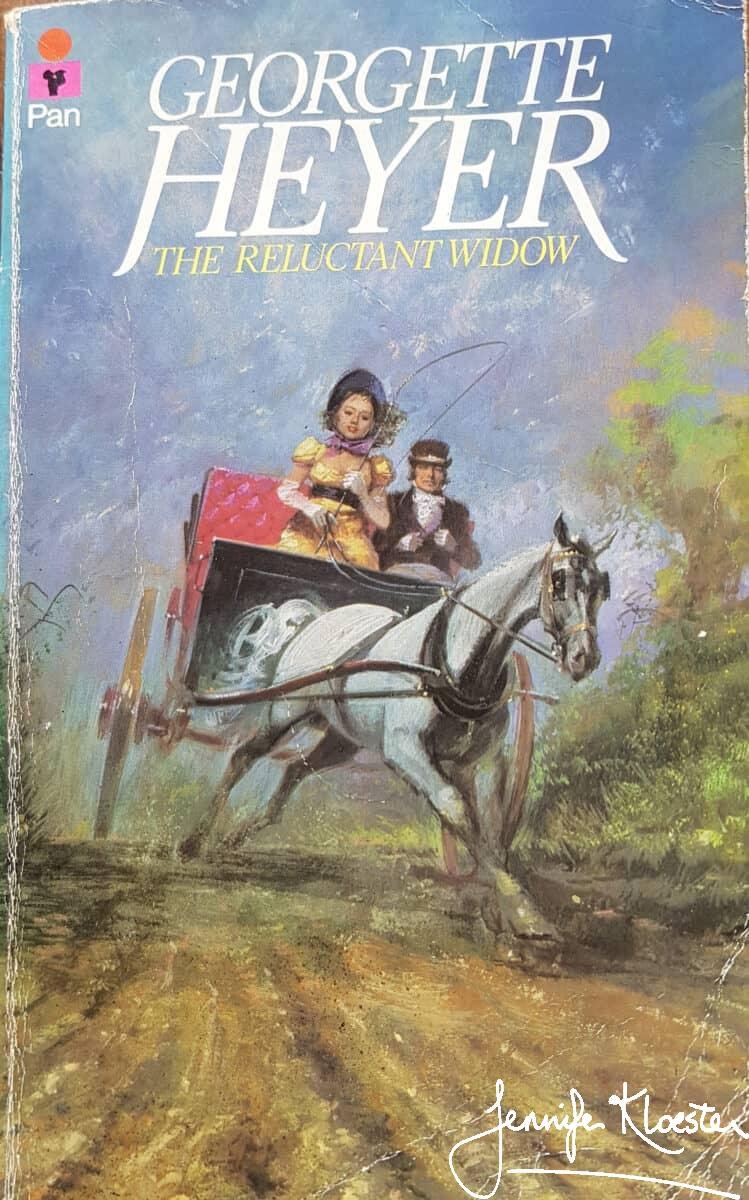

The 1962 Pan edition