“It has left my withers wholly unwrung”

On 1 October 1970, Georgette Heyer’s penultimate Regency novel, Charity Girl, was published. On that same day, The Times newspaper published a long article about Georgette, her readers and her novels. It was written by well-known author, intellectual and radio personality, Marghanita Laski, and it was not complimentary. Despite having promised Georgette that Laski’s piece would “makes amends” for past neglect, the literary editor, Michael Ratcliffe (possibly because he had not read Laski’s piece or because he had read it and thought it incendiary enough to attract attention), allowed the article to be published. While Georgette herself declared herself unperturbed by the article, it aroused a storm of protest from her readers, many of whom wrote to The Times as well as to Georgette herself and to Marghanita Laski. The Times published half a dozen of the letters under the heading “Miss Georgette Heyer’s Regency Novels” before the Editor declared the matter closed. They make for interesting reading and reflect the points of view of readers from across the social demographic. The letters are given below and it seems certain that they must have given Georgette a good deal of pleasure. Her own response to Laski’s article was expressed in a letter to her friend and former publisher, A.S. Frere:

“What a remarkably silly “review” of Charity Girl it was! I thought, as I read it, that I could have torn ME to bits far better than she did. Not that it has done me the slightest harm, so it has left my withers wholly unwrung.’

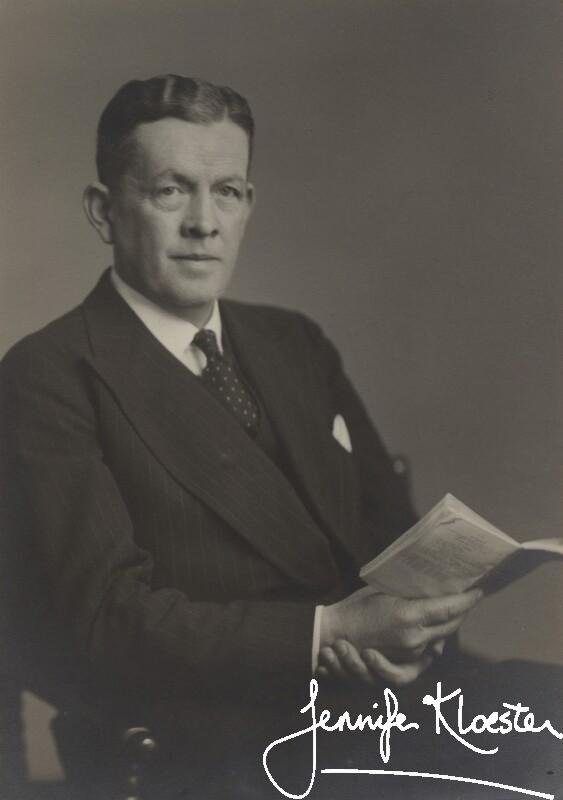

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter,

Readers reply to Marghanita Laski’s “review” of Charity Girl

Etching: Wikimedia Commons

“the deductions … are perhaps open to question”

Sir, The deductions of Marghanita Laski (review, October 1) concerning the books of Miss Georgette Heyer are perhaps open to question. For instance, she asserts that “the heroes…are invariably dandies”—and what is a “dandy”? A dandy is one who by sartorial distinction, dictation of social conventions, or both, seeks to distinguish himself from the common herd. In fact, very many of Miss Heyer’s heroes “fail” to come into this category, for instance—the Marquess of Rotherham, Mr Miles Calverleigh, and Major Theo Darracot [sic – he means Hugo Darracott]. As for the authenticity of the Miss Heyer’s portrayal of Regency England, I would, from my own knowledge of the writings about that period conclude, contrary to Miss Laski, that the portrait is archeologically correct—sufficiently so to be of some importance to the social historian in his understanding of that era. Miss Laski has for critical purposes juxtaposed Georgette Heyer with Jane Austen in a distinctly inadmissible way—bearing in mind that Jane Austen was writing novels of contemporary manners for her contemporaries, for the absence of detail necessarily used by Miss Heyer to give a sense of period to her present readership being explicable because this detail’s existence was understood between the writer and the reader, and thus did not require inclusion. However, I must agree with Miss Laski that the lack of sexual motivation in the behaviour of the characters is too noticeable, and is a detraction from essential human authenticity, “Regency” or otherwise.

Yours faithfully,

Peter Arnold, letter, The Times 3 October 1970

“Laski has not read the Regency novels very thoroughly…”

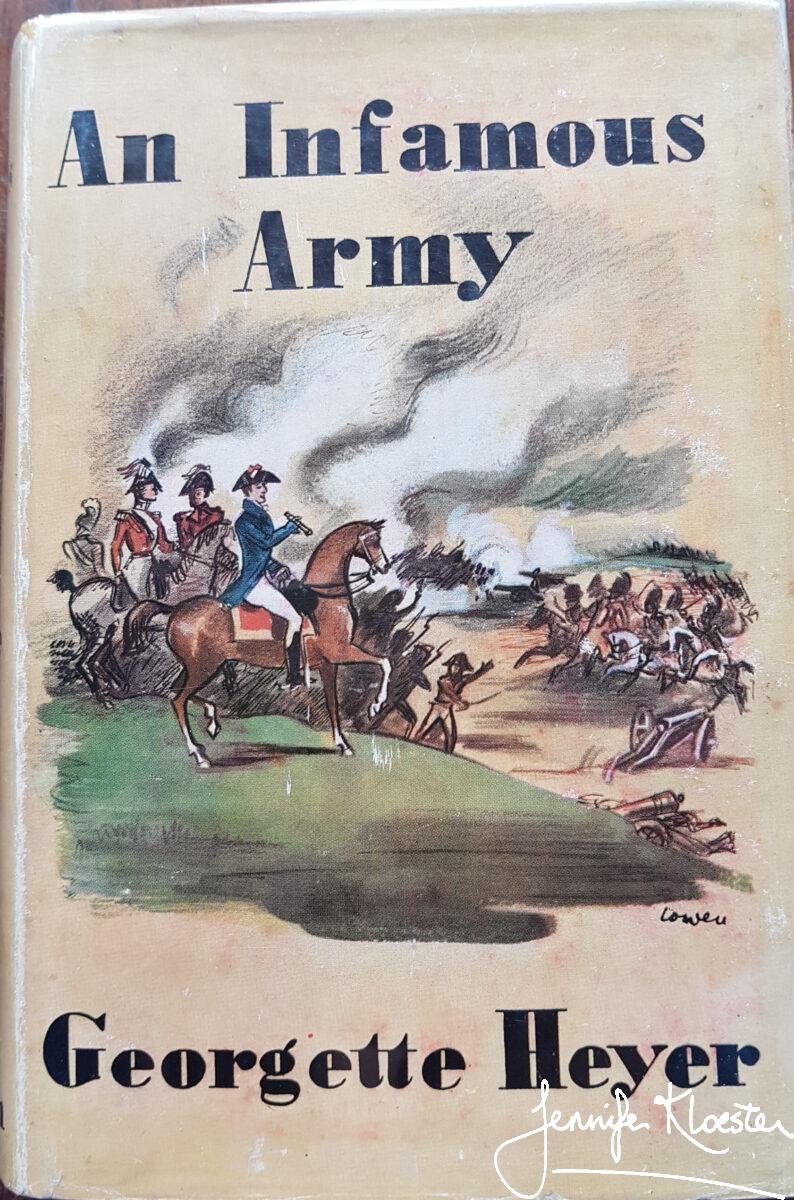

Sir, Miss Marghanita Laski has obviously not read the regency [sic] novels of Georgette Heyer very thoroughly (review, October 1). This is understandable, as she doesn’t like them much, but necessary in order to generalize. In fact, there is dirt, plenty of mud, dust and blood; there is poverty in The Toll-Gate (working-class), Arabella (middle-class); religion of the ordinary Christian kind in evidence, more particularly in Arabella; an occasional [sic] political background (Bath Tangle and the war novels. There are squalid scenes in the streets, there is cruelty to children, to animals. There is noise. Certainly sex is limited. Miss Laski might have found more powerful indications of lustful sex in The Spanish Bride—in which the hero and heroine are actually happily married—or even The Infamous Army [sic], in which the physical attraction between Audley and Lady Barbara is plainly the chief reason for their relationship. I believe it is true that no married man is allowed to have a mistress, although he may visit her to say goodbye (The Convenient Marriage), but the heroes are permitted to carry on with other women both in the pages of the book and while the heroine is about (These Old Shades). The heroes are not all “dandified”, some go out of their way to be thought not so—Charles in The Grand Sophy—or don’t mind what they wear (Black Sheep), and actually the dandies are gently made fun of (Cotillion). People, men too, read Georgette Heyer because they find her books witty, entertaining, well-written—no doubt characters do “gaze up at” each other but so they do in Iris Murdoch—and the detail graphic, interesting and not unreliable. Even dogs and horses are marvellously real. They are romantic novels and as such can hardly put a mirror up to life n all its realities. So, of course, there are inanities, and however did those heroines disguised in men’s clothing “manage”? I am, sir, yours, &c.,

ROSALIND BELBEN, letter, The Times, 3 October 1970

“appeal to educated men”

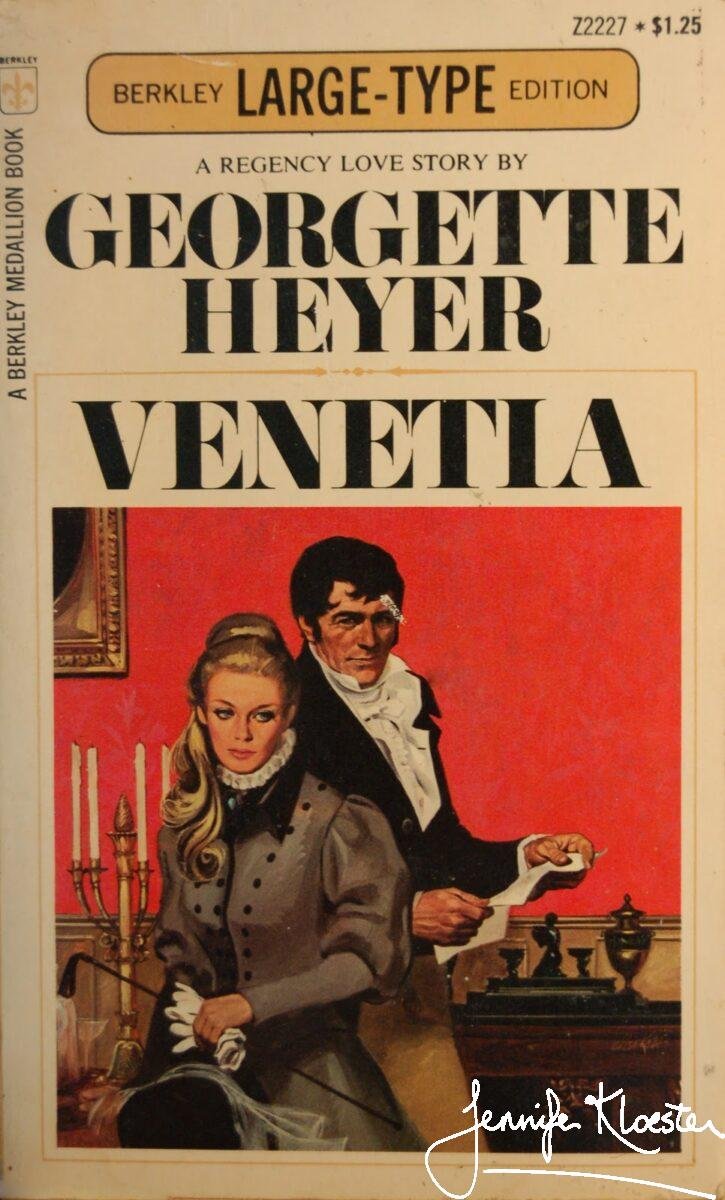

Sir, Marghanita Laski marvels that educated women read and enjoy the Regency novels of Georgette Heyer. But she appears unaware that they can also appeal to educated men. My father, Professor Sir Richard Lodge, a serious historian, introduced them to his family with much appreciation. My brother, Balliol, ex-schoolmaster and scientist, had an almost complete collection of them in paper-backs. They sparkle with wit and humour and make delightful escapist reading. Personally I can read them again and again and still unexpectedly chuckle aloud. The Reluctant Widow is my favourite. It is surely a curious criticism that there is so much detailed description of “food, clothes, furnishings, transport” in those Regency novels as contrasted with the novels of Jane Austen. Jane Austen was writing in the period, Georgette Heyer is writing of it and creating a picture by those careful details. If it is a glamourised picture, so much the better! There is little glamour about the modern novels which Marghanita Laski prefers, and which I return to the library after reading a few pages. Chacun a son goût! Yours truly

MARGARET B. LODGE, letter, The Times, 3 October 1970

“refreshment and amusement”

Sir, Referring to Miss Marghanita Laski’s review, The Appeal of Georgette Heyer, I think it is just the “lack of sex” decried by Miss Laski that appeals so much in Miss Heyer’s books. I read and enjoy many of the novels published today which contain very frank and open relationships, but I turn to Georgette Heyer for refreshment and amusement—the humour of Miss Heyer is not mentioned by Miss Laski—as I think many women do. I find her books quite delightful and to introduce sex between her lovely heroines (in reduced circumstances but well born) and her wealthy, masculine heroes would be traitorous! Yours faithfully,

ANNE E. LIMEBEAR, letter, The Times, 3 October 1970

“one of the best descriptions of the Battle of Waterloo”

Sir, As a bookseller for forty years I should like to support those who say that Georgette Heyer’s novels appeal to “educated people”. And when books were out of print after the last war we had to obtain a copy of “The Infamous Army” [sic] for the late Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart who wanted to give it to our Embassy in Brussels as it was, he said, “one of the best descriptions of the Battle of Waterloo”. Yours faithfully,

J. CHAUNDLER, The Blackdown Bookshop Ltd., letter, The Times, 6 October 1970

“Miss Heyer provides a beautifully written novel”

Sir, Marghanita Laski, and your correspondents all miss the secret of Georgette Heyer’s appeal to the middle-aged housewife. We don’t want works of art for our escapism, we don’t want emotion or facts of life of any description—we are surfeited with crying children, tired husbands, putting on weight and wearing a smile. What we want, and what Miss Heyer provides, is a beautifully written novel with a neat plot, witty dialogue and good characterisation, in a romantic world where the girl captivates the hitherto unattainable hero and is in consequence looked after, considered and protected to the hilt in a way that almost never happens in real life! Yours faithfully,

SUSAN HORSLEY, letter, The Times, 7 October 1970

A letter from Lucy Boston

Dear Georgette,

As you know, I don’t often send you fan letters, but I think you should see this one from Lucy Boston, who is a distinguished children’s author of ours, as I think it might give you some pleasure.

Yours ever, Max Reinhardt

Max Reinhardt to Georgette Heyer, letter, 6 October 1970

Georgette wrote two letters to Lucy Boston, but sadly neither author kept the other’s correspondence, so we will never know what they actually said to each other. That it was complimentary in both directions is certain and in the end Georgette had only one thing to say on the matter:

The final word from Georgette

Yes, wasn’t the correspondence fun? I’ve had lots of letters like Lucy Boston’s and one Fan has actually written to the Laski, telling her where she gets off!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 11 October 1970