“I’m writing to ask you a favour”

Dear Mrs. Rougier, I’m writing to ask you a favour. I wonder if you would consider waiving your quite reasonable distaste for being photographed and allow me to send a photographer from The Times at some point in the next two or three weeks. As you probably know, Marghanita Laski is a great admirer of your work and is going to write for me a lead piece on Charity Girl and its predecessors on October 1. It would give me great pleasure to publish with this review a fine new photograph of the author. We could make our choice from a number of pictures and I think I can promise you that we should do it most carefully since our aim will be to complement the notice with the portrait. I fully understand your reticence, particularly since we “Quality” newspapers have not exactly devoted a vast amount of space to your work in the past few years, but we do promise to make amends on this occasion and Marghanita is doing her homework very thoroughly. I shall be delighted if I can persuade you.

Yours sincerely,

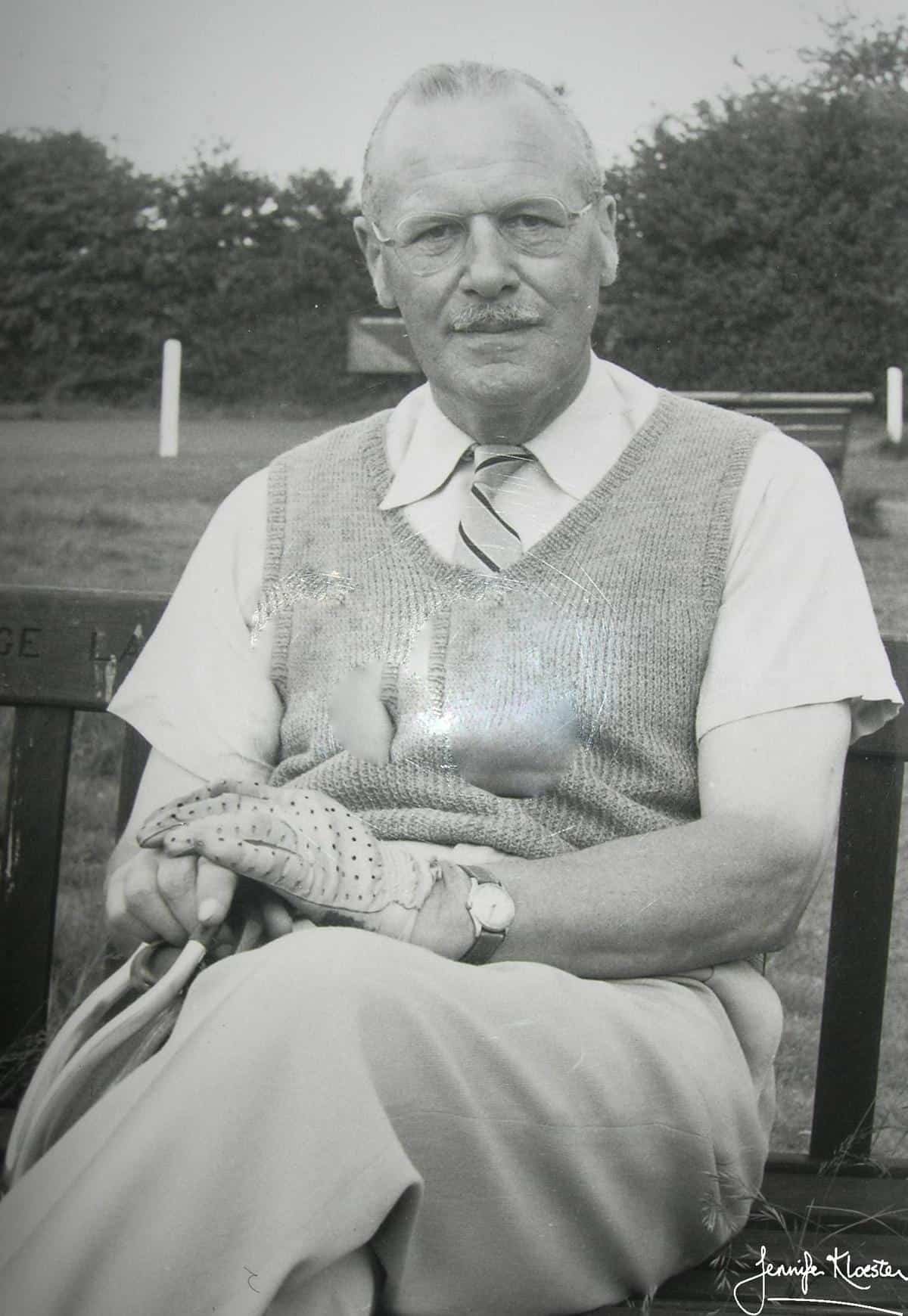

J. Michael Ratcliffe, Literary Editor, The Times, letter to Georgette Heyer, 4 September 1970

“Ronald has persuaded me”

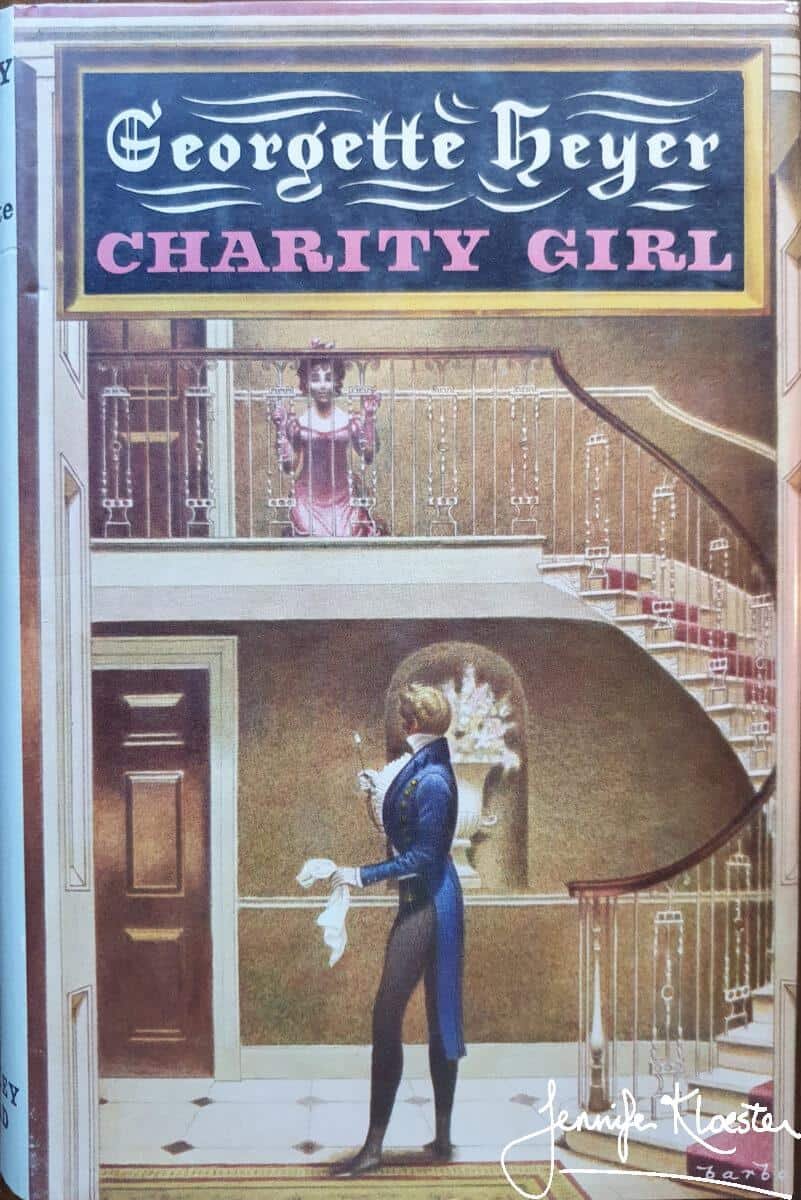

It was a flattering letter, but Georgette was not keen. She was by now a huge international bestseller. Apart from the six novels she had herself suppressed, all of her books were still in print and her sales numbered in the millions. By the mid-sixties she had become a household name and her fans eagerly awaited their annual “Georgette Heyer” novel – hounding their booksellers if it did not appear. Charity Girl was to be Georgette’s fifty-fourth novel, and even before publication the subscription was enormous. It is not surprising that The Times wished to do a piece about her. Although she would not consent to an interview, Ronald eventually persuaded her to agree to be photographed. Georgette wrote to her adored publisher, Max Reinhardt to ask:

Darling Max,

Did you have anything to do with the enclosed request? As I’ve told Mr Ratcliffe, my first impulse was to write and tell him I’m just off to the South Pole, but Ronald has persuaded me to give way. He says I really must be photographed just once more, or there won’t be a photograph for my obituary notice! So I’ve asked Ratcliffe to ring me up next Wednesday morning, to fix a date. Not that I think our flat at all a suitable place for indoor photography, but that’s his worry!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 9 September 1970

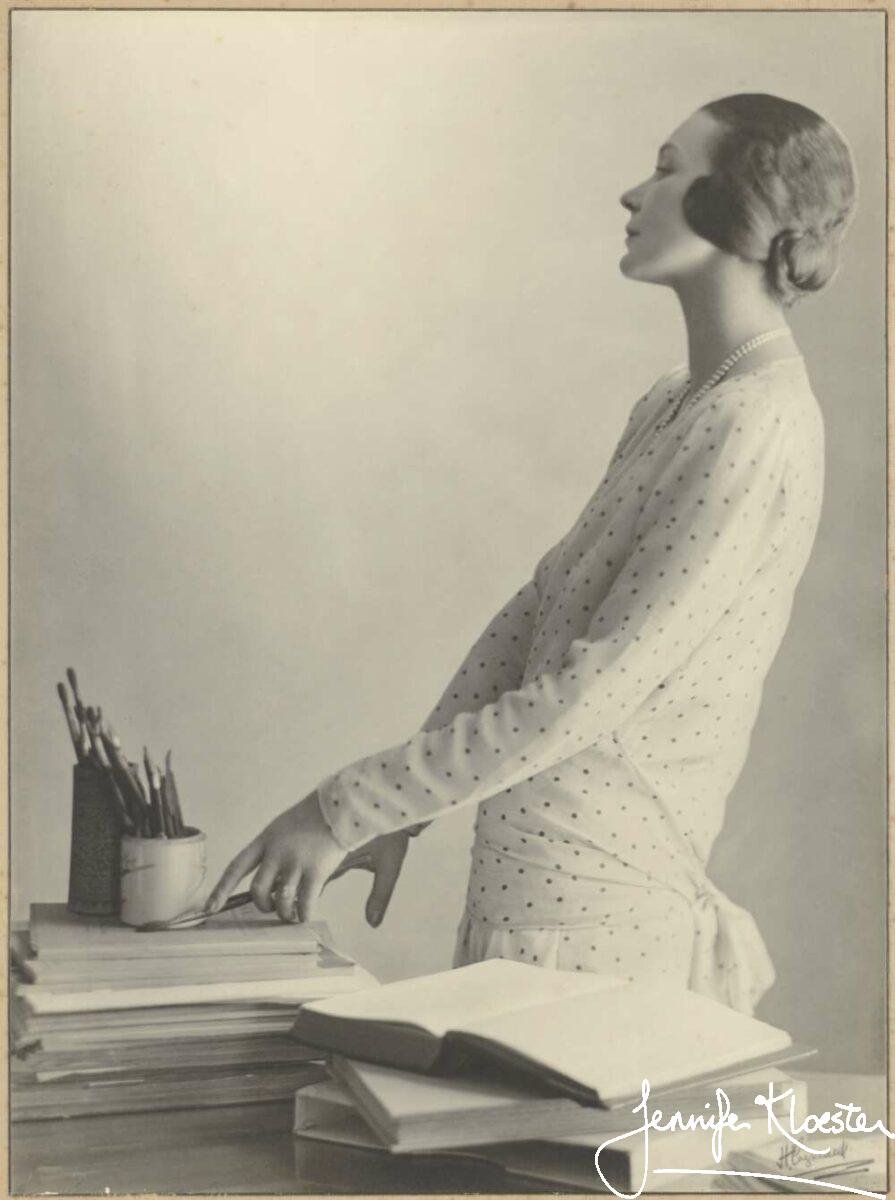

Reinhardt assured her that he had had nothing to do with the proposal but nevertheless was pleased that Georgette had agreed to be photographed. In due course the fateful day came and the Times photographer arrived at Flat 4, 60 Jermyn Street to find Georgette at her imperious best. She had dressed for the occasion in a well-cut skirt and jacket with her hair coiffed and a four-strand necklace of natural pearls around her neck. This last-ever formal photograph would see Georgette sitting with perfect posture in a straight-backed chair, a sceptical lift to her brows and – if one looks closely – the faintest hint of a smile. Behind her is a large bookcase crowded with reference books and at least one visible title is The Age of Napoleon by J. Christopher Herold, published in 1963. There is not a single one of her own books to be seen on any shelf. Although Ratcliffe as literary editor had promised her that “We could make our choice from a number of pictures and I think I can promise you that we should do it most carefully since our aim will be to complement the notice with the portrait”, Georgette did not see the photographs until the one chosen by The Times appeared in the paper.

Photo: the National Portrait Gallery, London

Marghanita Laski

Marghanita Laski was born in Manchester to a prominent family of writers and intellectuals. Her father was a judge and her grandfather the famous British scholar, linguist and Zionist, Moses Gaster. She had a first-class education, and attended Somerville College, Oxford, where she studied English. Marghanita met her husband-to-be, John Eldred Howard while she was at Oxford. Married in 1937, she had two children, before commencing her writing career in the early 1940s. Her first novel was published in 1944 and over the next thirty years she wrote novels, plays, short stories, screenplays, and in the 1960s and 70s produced biographies of Jane Austen, Rudyard Kipling, George Eliot and Charlotte Yonge. Laski was also a major contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary. By 1986, she had added some 250,000 quotations to the dictionary making her “the supreme contributor, male or female, to the OED”. A clever writer and intellectual, in the 1950s and 60s Laski was a panellist on several popular BBC panel shows and she also worked as a columnist and critic. By the time of her death in 1988, she had more than two dozen publications to her name; today most of these have disappeared from view. After her disparaging article about Heyer appeared in The Times Georgette’s agent, Joyce Weiner, told her that she had “known M. Laski since they were both girls” and “that she is consumed by jealousy!” We will never know what prompted Marghanita Laski to write as she did – but her article raised a storm of protest from readers, so many of whom wrote to The Times that, after publishing several of them, the editor had to declare the matter closed.

“The Appeal of Georgette Heyer” by Marghanita Laski

On 1 October 1970 Georgette Heyer’s new novel, Charity Girl, was published to an eager audience. On that same day, The Times published Georgette’s photograph beside Marghanita Laski’s article under the promising title “The Appeal of Georgette Heyer”. The title was deceptive. Although Michael Ratcliffe had promised that the paper would “make amends on this occasion” and that “Marghanita is doing her homework very thoroughly”, Laski’s article was, as Jane Aiken Hodge aptly described it, “a four-column sneer at once at the books, their readers and, by implication, their author.” Reading the article today, one cannot help but wonder at Ratcliffe’s assertion that “Marghanita Laski is a great admirer of your work”. Given the persuasions offered to Georgette by the Times’ editor in order to have her agree to be photographed, the article must have come as something of a shock. Here is the article quoted in full with my interpolations in bold between the paragraphs:

Ever since the serious novel deprived itself of the pleasure of the shapely story satisfactorily resolved, serious but compulsive novel readers who need the shapely story as a drug have had to turn, for this part of their need to the popular novel. Often it is easy to see why such books appeal to both non-intellectual and to intellectual: the gratifications to be gained from many thrillers, detective stories, science fictions and, of course, from Hornblower, are easy to discern. The Regency novels of Georgette Heyer constitute another and more difficult case. Their appeal to simple females of all ages is readily comprehensible. But why, alone among popular novels hardly read except by women, have these become something of a cult for many well-educated middle-aged women who read serious novels too?

One cannot but wonder at this continuing need by critics to denigrate “the popular novel”. Why is there an innate (and illogical) assumption that “popular” cannot equal good, worthy, well-written, or literary? What does Laski mean by non-intellectual? Is she suggesting that these readers are stupid? What is a non-intellectual and who and what distinguishes them from the intellectual reader? Laski’s tone is patronising and sexist. Her denigration of so-called “simple females of all ages” is extraordinary and incendiary.

For men, a brief description may be helpful. Among other books, including detective stories, Georgette Heyer has for some 40 years been producing novels set in a kind of Zinkeisen-Regency England of which the latest, Charity Girl, is published today. They are entirely concerned with love and marriage among an upper class that ranges from wealthy dukes to wealthy squirearchy. The heroes, usually demoniac, but occasionally gentle, are invariably dandies. The heroines may be spirited and sophisticated, spirited and naïve, or, increasingly of recent years, common-sensible. By miscomprehension and misadventure, hero and heroine fail to achieve mutual understanding until the end.

Incredible that Laski feels the need to “mansplain” – to MEN – here! So far from “doing her homework very thoroughly” it is clear that Laski has no clue about Heyer’s readership and is ignorant of the fact that, from her earliest books and right up to the time of this article, Heyer was read by both men and women of all ages and classes. Her comparison of Heyer’s Regency England to the work of the famous theatrical and film designer, Doris Zinkeisen, is not meant as a compliment. Zinkeisen was a brilliant designer renowned for her “flair” and “fantastic treatment” in creating wonderful costumes for the stage and screen. Laski’s apparent take on Heyer’s Regency World is that it is nothing more than its creator’s fantasy. As for Laski’s comment that her Heyeroes are “usually demoniac” and “invariably dandies” one can only wonder whether she had actually read more than a handful of Heyer novels. She certainly can’t have read Charity Girl whose hero is decidedly NOT demoniac!

Since nothing but the Regency element distinguishes these books from the best of the many thousands that used to fill the “B” shelves in Boots’ Booklovers Library, it must be this element that gives the stories their special appeal, and this element is very odd indeed, for Miss Heyer’s Regency England is not much like anything one infers about that time and place from more reliable writings, whether fiction or fact.

Really? Laski seriously can find nothing but the “Regency element” to distinguish Heyer’s novels from any others? She must have missed the wit, the humour, the brilliant dialogue, the flesh-and-blood characters, the compelling plots, the imbroglio endings, the historical detail, the meticulous research, the sparkle, the joy and the delight that make Georgette Heyer’s novels favourite re-reads for millions of people. Perhaps it is a good thing that Ms Laski is not alive to see the huge and lasting appeal of the Regency genre that Georgette Heyer created. If she were, she would undoubtedly marvel at the apparently insatiable appetite for Regency-set stories – whether they be books, films or television series such as Bridgerton. It is impossible to know what Ms Laski may have inferred from “more reliable writings” about the Regency – but she has clearly missed the wealth of accurate historical detail in Heyer’s 26 Regency novels!

That Miss Heyer has done a lot of work in the period is obvious. Any of her characters may talk more “Regency English” in a paragraph than is spoken in Jane Austen’s entire corpus. Real people often appear, such as Beau Brummel [sic] and Lord Alvanley and, of course, Lady Jersey, since whether or not the heroine will be admitted to Almack’s is often a grave crux—she always is. Any individual Heyer novel can be an extremely enjoyable pastime, but the more Heyer novels one reads the more one recognizes the same limited props, slightly rearranged on the stage. Smart chairs are covered in straw-coloured satin, smart gloves of York tan are negligently pulled on, buttered lobsters are toyed with at elegant meals. Hardly a hero but has a multi-caped coat tailored by Weston, is envied by young cubs for his mastery of the neckcloth. Hardly a dashing heroine but takes the ribbons of a phaeton. Hardly a novel but introduces a Tiger or Game Chicken to exemplify the language of the Fancy in which Miss Heyer is especially deft.

It’s nice that Laski notes Heyer’s “work in the period” (albeit in a condescending tone) and true that there is more cant than ever appeared in an Austen novel. Of course, the two authors were doing very different things. While a good critic may indeed compare Georgette Heyer to Jane Austen – especially given that the former drew inspiration from the latter and repeatedly pays homage to Austen in her novels – one does become tired of those who delight in pointing out that Jane Austen did not explain to her readers those things which would have been OBVIOUS TO THEM! As has been repeatedly stated by better-informed critics: Austen was writing contemporary fiction for people who already knew and understood her world because they were living in it; Heyer is writing historical fiction for readers who live and dress very differently from the characters in her novels. As for the claim of limited props, and there being “a Tiger or Game Chicken” in every novel, never mind that apparently almost EVERY heroine is dashing and can handle the ribbons in form (actually only 4 out of 26), it seems safe to conclude that Ms Laski has in fact read very few Heyer Regencies.

But those aspects of life on which Miss Heyer is so dependent for her creation of atmosphere are just those which Jane Austen (and other novelists for years to come) referred to only when she wanted to show that a character was vulgar or ridiculous. Food, clothing, furnishings, transport—it is because those matters engrossed a Lydia Bennet, a John Thorpe, a Mrs Elton, that we know them to be morally and socially worthless. Though Jane Austen’s letters show how greatly clothes and furnishings, at least, interested her personally, it would obviously be entirely improper for them to interest her in relation to commendable characters. It is possible, even probably, that Fitzwilliam Darcy wore a many-caped coat built by Weston; it is unthinkable that we should know that he did..

The only thing to add to my response above is to say that Georgette Heyer knew very well how to use food or clothing or transport to reflect a character’s moral or social worth. The scene in The Grand Sophy where Eugenia begs “to be allowed to take the back seat” of the landaulet and Cecilia instantly insists “that she should not” is just one of myriad examples in Heyerdom. In a single sentence she tells the reader something important about each young female’s character: in “begging to be allowed to take the back seat” of the landaulet Heyer shows us Miss Wraxton’s innate sense of moral superiority as manifested in this self-conscious act of apparent sacrifice, while Cecilia, seeing through Eugenia’s pseudo-piety, is equally determined that she – and not her brother’s unlikeable fiancée – will be the one to secure the least comfortable seat in the carriage and thereby baulk Eugenia’s attempt at martyrdom. It is worth noting here, that more than halfway through her article, Laski still has not written specifically about Charity Girl or its predecessors.

It is not, then, in respect of decorum that Jane Austen has influenced Georgette Heyer but the influence is there, at least in the early books, in some balance and turn of sentences: “We talked of all manner of things until I was comfortable again, and I do not think there was never [sic] anyone more good-natured”—There is certainly an echo of Harriet Smith here. But “her characters was no use! They was only just like people you run across every day”, as Kipling’s soldier said of Jane Austen; they are several social steps below Miss Heyer’s chosen ambience, and infinitely less glamorous. A model nearer in feeling and event would be Fanny Burney’s much earlier Evelina. But not there, or in Jane Austen or Maria Edgeworth or even Harriet Wilson does one find Miss Heyer’s extraordinary dandified heroes. There were dandies, but they were jokes, not heroes. Is it the shade of Sir Percy Blakeney that knocks at Miss Heyer’s door? If so, his shadow is the only one that falls on this pseudo-Regency in which there is almost no dirt, no poverty, no religion, no politics (a short step to silence in books for women). I have still got no nearer to discovering why Miss Heyer’s books appeal to so many educated women, but I know what lack of shadow it is that makes them of only limited appeal for me. It is because they have no sex in them.

The first part of this convoluted paragraph offers some small acknowledgement of the effect of Austen on Heyer, but why bring Kipling into it? Here again, Laski demonstrates her ignorance of Heyer’s oeuvre. One has only to read Bath Tangle for politics; Arabella for dirt and poverty; Cotillion for religion, and Venetia for superb sexual tension. Clergymen loom large in Austen’s novels and they play vital roles in most of her stories; Heyer uses clergymen and religion differently, but it is there for those who have the wit to see. As for the “extraordinary dandified heroes” one can only wonder at Laski’s meaning. While some of Heyer’s heroes have things in common and several are indeed dandies, no two are the same, and some are not particularly interested in clothes and certainly not in turning out in “prime style” (Miles Calverleigh or Hugo Darracott anyone?).

Now I realize that the popular romantic novel must be without overt sex, especially if it is to sell in tat holy of holies of the trade, Irish convents. [Okay, I really have to cut in here – WHAT is she talking about? Since when does the publishing industry rely on selling novels to Irish convents?] But not to say anything nasty is not necessarily the same thing as not to imply that sexual drive exists. In a good popular novel, be it overtly as clean as a whistle, we should never doubt that to put in the dirty bits would be merely to expand it and not to alter it or, as it would be in Miss Heyer’s case, to shatter it. We have never doubted the sexual passion that linked Sir Percy and Lady Blakeney throughout their alienation. Stanley Weyman’s depressed heroes suffer from real lust, his heroines are in danger of real rape. Even for Charlotte Yonge the sexual relations of her characters were at least implicit (and for what can be achieved within reticence, try her historical novel Love and Life). A counter-bowdlerizing expansion could be undertaken on any lastingly worthwhile popular novelist.

Needless to say, Ms Laski has NOT read Venetia! Or The Masqueraders, or These Old Shades, or Devil’s Cub, or Faro’s Daughter, or The Corinthian, or…

But if Miss Heyer’s heroines lifted their worked muslin skirts, if ever her heroic dandies unbuttoned their daytime pantaloons, underneath would be only sewn-up rag dolls. Her mariages blancs could run till doomsday without either partner displaying nervous strain; her heroes can, as in this latest, roam the country with unprotected young girls who need never fear loss of more than a good name. Certainly the odd hero may have had his opera dancer before he enters the heroine’s (and our) ken, but not inside these covers. So long as the puppets are out of their box, a universal blandness covers all.

I do have to chuckle a little bit here because, despite promising to do her homework, Laski seems oblivious to the fact that Georgette Heyer began writing bestselling novels in 1919 when she was only seventeen. Until 1960, her career spanned an era when, even if she had wanted to, Heyer would not have been allowed – either by her family or the state – to write overtly about sex. Prior to Penguin Books winning the 1960 court case over D.H. Lawrence’s sexually graphic novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, frank descriptions of sex in novels were taboo in Britain. By 1960, Heyer had been published for fifty years and was not suddenly going to change her phenomenally successful writing style to include scenes that would take her readers past the bedroom door. Heyer was also aware of the very real constraints imposed by the realities of her chosen historical period. While illicit sex certainly happened, it did not usually happen between young unmarried upper-class women and their potential suitors.

As for the “universal blandness” remark, nothing could be further from the reality of reading a Georgette Heyer novel.

Were we to take Georgette Heyer simply as a novelist for women whose only novel-reading was popular romance, she would deserve the highest praise. As the genre goes, her books are better than most, and more complicated; it often takes a couple of chapters to guess who will finally marry whom. The Regency element is pleasantly novel and the props, if limited, are genuinely period pieces. But the appeal to educated women who read other kinds of novels remains totally mysterious unless—is it?—could it be?—these dandified rakes, these dashing misses, the wealth, the daintiness, the carefree merriment, the classiness, perhaps even the sexlessness, are their dream world too?

Not much of a fan of the female reader was Marghanita Laski! Her patronising tone and extraordinary condescension – both to Heyer and to her female readers (she did not see fit to acknowledge Heyer’s male readers) – merely supports Joyce Weiner’s assertion that Laski “is consumed by jealousy”. Perhaps this was true. Certainly, Laski’s novels had never achieved the enormous success that Georgette Heyer had always enjoyed.

It was not the promised article and it most definitely was not a review of Charity Girl, and although upon reading it Georgette declared her “withers wholly unwrung” , it must have stung. There was a little more to come, however, in the form of outraged letters of protest to The Times from her fans… (next week)

Marghanita Laski, “The Appeal of Georgette Heyer”, The Times, 1 October 1970

2 thoughts on “Charity Girl – against the odds part 2”

I had forgotten this. Thank you and for your glosses. What is true is that Laski is writing at the time of the kitchen sink drama, Room at the Top etc. The metropolitan zeitgeist was not faux Regency. And it is faux . We enjoy it like Cinderella’s ball. So of course was Jane Austen’s. We are not told about the source of the Bertram’s labour. We hope Wentworth’s fortune will be big enough to last because there will be no more prize money. We do know the consequences of sexual sin, death, from Sense and Sensibility, but Lydia escapes as does Mrs Clay. The issues are touched on but the context is circumscribed, save possibly in The Tollgate and The Nonsuch. Mind you, it’s only Mary Challoner’s tumny that saves her from rape before the pistol episode. ML cannot conceive of a genre worth serious study that is about enjoyment. And I think deep down GH probably agreed. Otherwise why spend so much time on My Lord John? Why be so disparaging,? She knew the craftsman ship was good. But she couldn’t see that she was writing Cosi or Figaro, also a limited and magic world, war to one side. But she wasn’t serious and for that she wasn’t up to ML’s standards.

Thanks for your excellent comment. Heyer’s Regency is a fascinating mix of historical fact and enjoyable fantasy. She certainly thought that her Regency word ws accurate down to the smallest detail butshe also recognized that she was writing fiction. The funny thing about My Lord John is that when you add up the actual time she spent researching and writing it – it wasn’t all that long. The length of time came in the time that passed between beginning it, then putting it aside and then taking it up again. I think that was about 18 years all up. She never did finish it, of course, and I think that’s because she didn’t have the same faith in her ability to recreate that world. Heyer knew that she was a first-rate storyteller and writer, but she needed some kind of magical affirmation – the elisive affirmation that so many authors need. I wish I could more fully answer your (rhetorical, I suspect) question about her being so disparaging – it has puzzled and frustrated me for years! Thanks so much for posting. I agree with much of what you say.