Just read the typescript of my first Spanish Bride chapter. Distinctly Good!

Georgette Heyer to Leonard Moore, letter, 14 July 1939

Inspiration!

On March 25 1939, Georgette Heyer told her agent that she had “been offered Sir George Scovell’s diaries to read – never published.” Scovell had been an officer during the Napoleonic Wars and a member of the Intelligence Branch of the Quartermaster General in Spain. He proved to be a brilliant code-breaker and was a key figure in deciphering the Grande Chiffre – the French army’s secret codes used to relay information about their military plans and operations during the Peninsular Campaign – and he later became Wellington’s chief cipher officer. As Georgette noted, Scovell was on the “Q.M.G. staff throughout the Peninsular War” and, while she predicted that his diaries might be “dull in the main”, she was hopeful they would be “packed with army information” and described the offer of the diaries as “Rather nice, don’t you think”. Scovell’s personal diaries were likely the inspiration that prompted Heyer to write the story of Harry Smith and his adventures during the Napoleonic Wars. It was not the first time she had thought of writing a book about Smith, however. Years earlier, in 1922, Georgette had mentioned in a letter that her father was enthusiastic about “Smith” (although he was even more enthusiastic about the manuscript that would eventually become These Old Shades), and it seems likely that the “Smith” book idea – or draft, as it must have been in 1922 – was the book Georgette would write in 1939 and which she would call The Spanish Bride.

The Story of the Spanish Bride

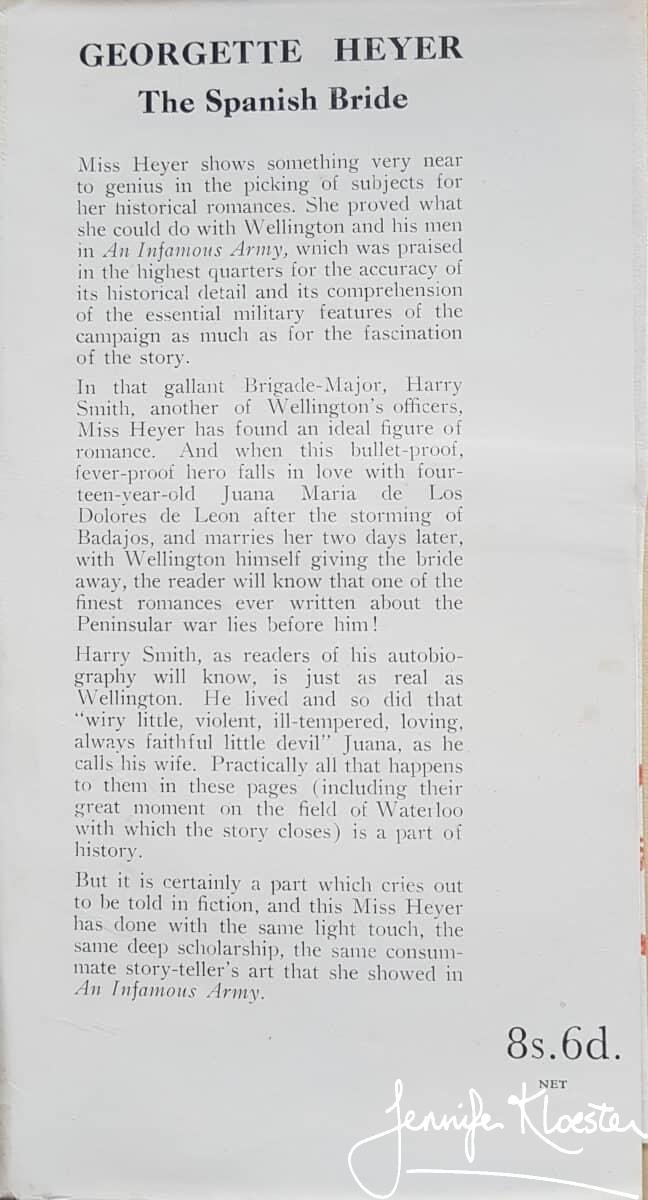

It was a story ripe for novelisation: the true story of Brigade-Major Harry Smith and his teenage bride, the feisty, aristocratic, Juana Los Dolores de León. They met on a battlefield in Spain, fell in love at first sight and were married in a drumhead wedding two days later with the Duke of Wellington as a witness. This incredible true story had struck Heyer from the first and her research for her Waterloo novel, An Infamous Army (in which the couple makes a brief appearance), published only two years earlier can only have encouraged Georgette to embark on this new and even more ambitious project. By August she had worked out the structure of the whole and wrote to her agent to tell him:

Here are the first two chapters of the Spanish Bride. I do not know how useful you will find them, for I am aware that, for serial purposes, much of the book will have to be cut – possibly a lot of the military detail. My system of chapters within chapters should make this a simple matter. I think the story would serialize very well. It will be all incident, & love-stuff. Chapter III will be the Salamanca one. Not going to do the battle in detail, as the Light Division was not engaged. But a few lovely bits, such as the terrific thunder-storm before the battle – lightning on the bayonets, Le Marchant’s horse stampeding. And Juana sleeping on the battlefield. Then the Madrid chapter – not long. The Smiths picking up a Spanish padre, & adding him to their cavalcade. The Retreat – Juana mixed up in a cavalry affair, having to swim her horse across a river. All sorts of nice bits. Winter quarters – balls & theatricals. The Vittoria campaign. Battle as from Harry’s point of view – Juana thinking him dead. Peculiar adventure with a madman after the battle. Then first appearance on the scene of Juana’s little pug dog, Vitty. The Pyrenees. Juana’s adventure with the Sèvres bowl, & other good bits. Toulouse & Harry leaving for America. Juana going to London. Juana in London, alone. Harry’s unexpected return. His going again. Then Waterloo, & Harry chartering a vessel to transport himself, his wife, horses, servants, & dogs to Ghent. Juana’s amazing adventures during battle of Waterloo. The report of Harry’s being killed. Her ride to the battlefield – Her meeting with Harry, safe and sound.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 11 August 1939.

The Spanish Bride has all of this and more, including some of Georgette’s truly lyrical passages as when she describes the “river-mist” and the “smoke-laden vapour” through which an onlooker would see the flash of muskets and the “figures of horsemen” that “seemed to flit restlessly in mazy convolutions”. This is one of Heyer’s early Regency-set stories and, along with An Infamous Army, it is one of her pivotal novels. It is through this book, The Army and Regency Buck that Heyer learned so much about the period, its people, customs and culture. A firm favourite with some readers, The Spanish Bride is not a common re-read – though it deserves to be.

By Nigel Cox, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12982707

Illness and War

Georgette began The Spanish Bride in April 1939 and had done some reading for it when she became ill. A week with Ronald at the grand Walpole Bay Hotel in Cliftonville, east of Margate, put her on the road to recovery, but in June she succumbed once more to illness. She told her agent that she was suffering from “cerebral anaemia”, a condition she described as “awful. This was a type of hypoxia or low blood pressure and she was to suffer from it for many months to come. Georgette found the next few months very challenging. War was looming and she was increasingly anxious about her finances. Her overdraft had grown to £1000, the bank was “getting very restive” and she could see no way of paying it off except by increasing her literary output. Unfortunately, she was already struggling to find time for her writing because she had been unable to replace her cook and maid and was having to manage with just “one daily help – very rough”. This meant that, as she explained, “I spend my time cooking”. Georgette had grown up with servants and maintained them throughout her married life. It was they who had made it possible for her to spend a large part of her time writing. Although in years to come, like most of her generation, Heyer would no longer have a cook or housemaid, in 1939 their absence made it much more difficult to produce the books that were her family’s main source of income. Added to this was the need for Richard (now seven) to have an operation and at least three weeks’ convalescence at home. Georgette found it impossible to write when he was unwell. All of these factors and the news of an impending and inescapable war only increased the pressure on Georgette. In August she confessed to Moore that

I honestly don’t know which way to turn, & it’s fast getting me down. My head begins to swim, always a bad sign. It would be awful if I went in for another of my nervous breakdowns.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 15 August 1939.

Two weeks later, on 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and on 3 September the Second World War began.

A remarkable achievement

It seems remarkable that, despite, her many challenges, Georgette Heyer still managed to write The Spanish Bride and loved doing it. Indeed, she described The Bride as “the only bright spot in an otherwise God-forsaken existence”. Though she was not a trained historian and, unlike many of today’s writers, never questioned her sources or such things as history from the top down, white privilege, or innate bias, Georgette took her research very seriously. For her, research meant going to the available original sources and relevant secondary sources, reading widely, and seeking out answers to difficult questions from those deemed authoritative enough to know them. In Heyer’s case, one of her main living authorities was Sir Charles Oman, the Chichele Professor of Modern History, Fellow of All Souls College and the British Academy, President of the Royal Historical Society and author of A History of the Peninsular War in several volumes. Among past records Heyer turned first to Sir Harry Smith’s Autobiography and Kincaid’s Adventures of a Rifleman, and then to Wellington’s Despatches and the personal accounts of soldiers and commanders involved in the various military campaigns. Unlike An Infamous Army, Georgette chose not to include a bibliography in The Spanish Bride. Instead she added an “Author’s Note” in which she listed her main references for her readers.

Original sources

Anyone wishing to read a couple of the original sources for The Spanish Bride will find Harry Smith’s Autobiography here on Project Gutenberg and Kincaid’s diaries here. A kind reader of my blogs recently wrote to me to point out that Georgette had sometimes used Kincaid’s words verbatim and to some extent this is true. A close reading of Part 8 of Chapter One, for example, shows that Heyer occasionally uses some of Kincaid’s exact words e.g. “a distant part of the kingdom” “For myself, I care not!”. For the most part, however, Georgette sticks as close to the original source as possible, while taking great care to rewrite it for the same or similar meaning but using her own words. Here are a couple of examples with Heyer’s words in square brackets in bold among the Kincaid’s original words:

“I was conversing with a friend the day after, at the door of his tent, when we observed two ladies coming from the city, [Kincaid saw two ladies coming towards them from the direction of the city] who made directly towards us; they seemed both young, and when they came near, the elder of the two threw back her mantilla[put back her mantilla with one thin hand.] to address us, shewing a [a handsome, careworn face was disclosed] remarkably handsome figure, with fine features, but her sallow, sunburnt, and careworn, though still youthful countenance, shewed that in her, “The time for tender thoughts and soft endearments had fled away and gone.” [The lady was no longer in the first blush of youth, but her features were fine, her eyes dark and liquid, and her bearing that of a princess]

Her husband she said was a Spanish officer in a distant part of the kingdom [She was married, she said, to a Spanish officer, fighting in a distant part of the kingdom, but whether he lived, or was dead, she knew not]; he might or he might not still be living. But yesterday, she and this her young sister were able to live in affluence and in a handsome house [Until yesterday, she and her young sister were living in quiet and affluence in one of the best houses in Badajos. A gesture indicated the figure at her side. ‘Today, senor, we now not where to lay our heads, where to get a change of raiment, or even a morsel of food! My house is a wreck, all our furniture is broken or carried off, ourselves exposed to insult and brutality – ah, if you do not believe me, look at my ears, how they are torn by those wretches wrenching the rings out of them!” She pointed to her neck, which was blood-stained.]—to day, they knew not where to lay their heads—where to get a change of raiment or a morsel of bread. Her house, she said, was a wreck, and to shew the indignities to which they had been subjected, she pointed to where the blood was still trickling down their necks, caused by the wrenching of their earrings through the flesh, by the hands of worse than savages who would not take the trouble to unclasp them!

It is interesting to see how Heyer altered the descriptive words of Kincaid’s narrative to ensure that she did not copy the original text word for word in her story. When it came to quoting words used in dialogue or when she is repeating something from the original source – as in the bit in bold in the second quotation above – she seemed happy to quote directly. I think this is because Georgette deemed it acceptable to use Kincaid’s own words when they were coming from Kincaid’s mouth or were his thoughts.

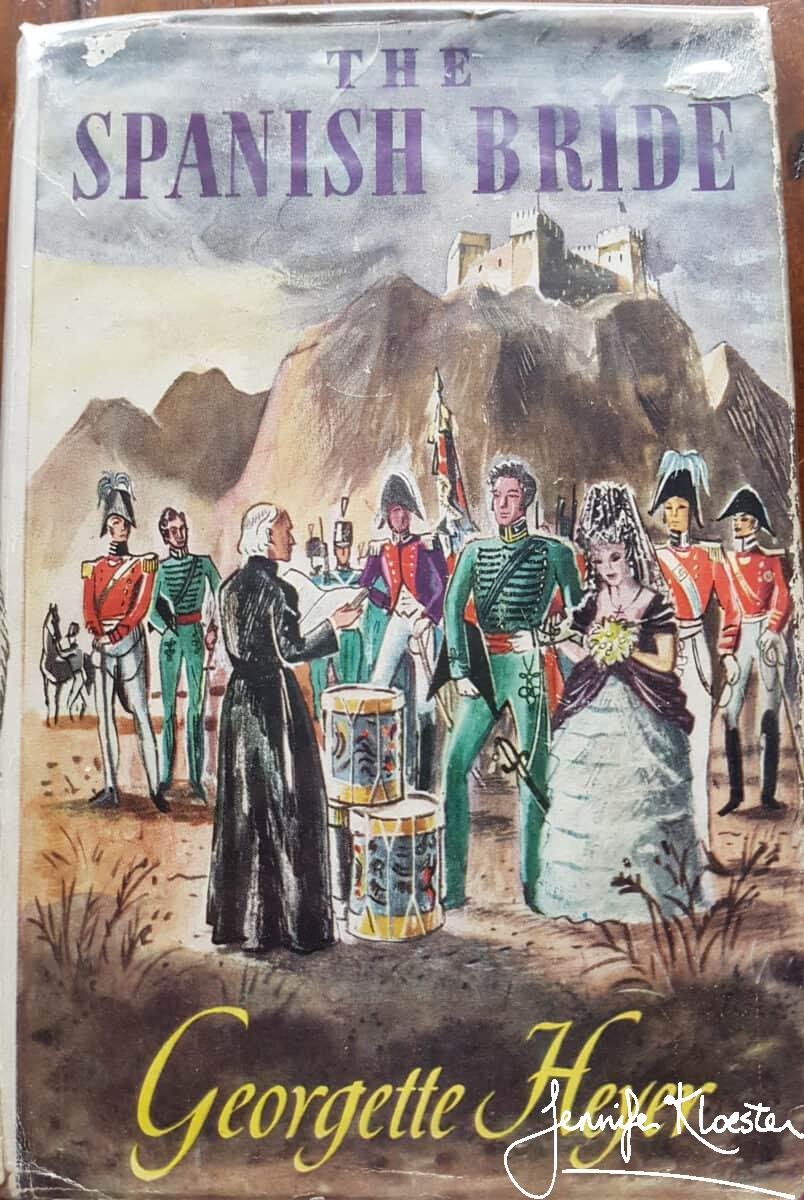

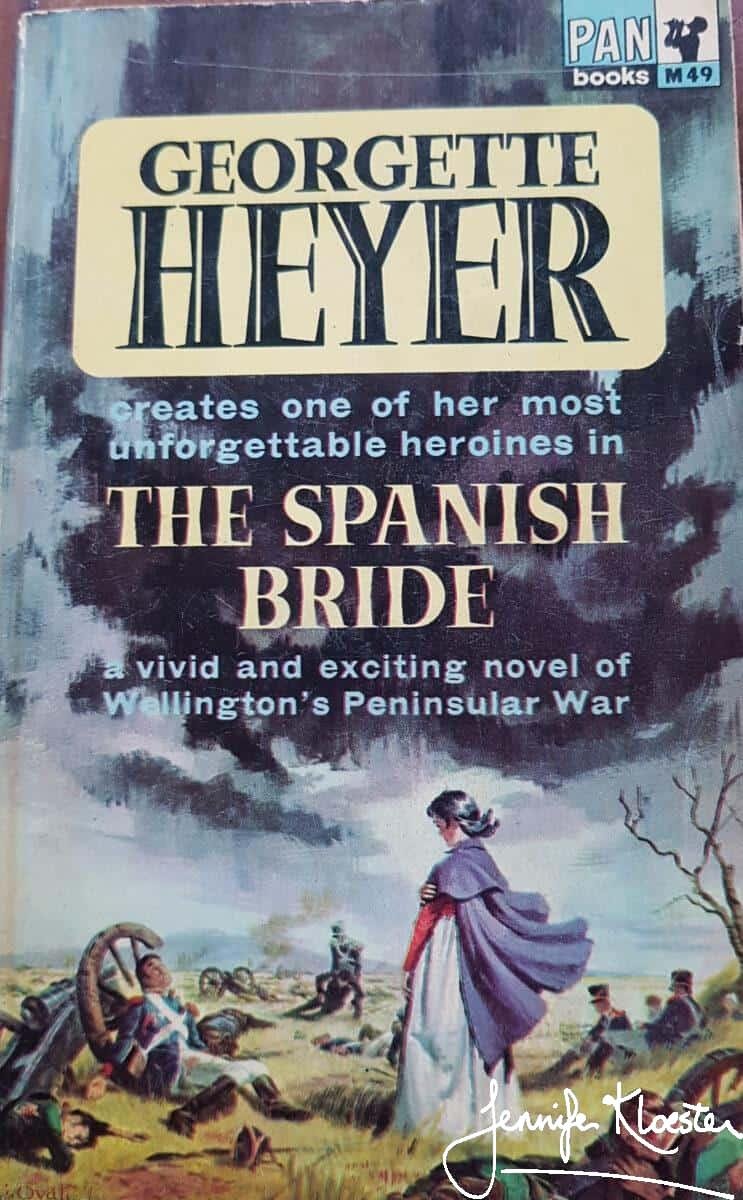

The 1964 Pan edition of The Spanish Bride

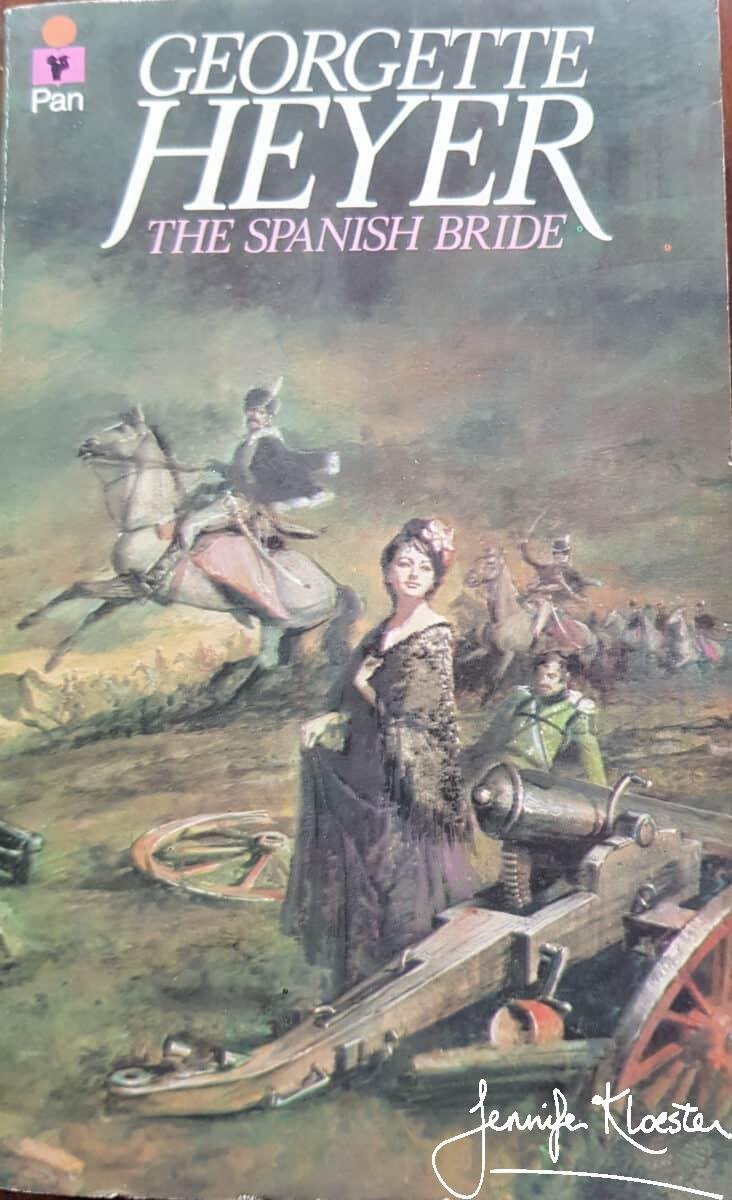

The 1972 Pan edition of The Spanish Bride

Written in less than six months!

It seems incredible that Heyer wrote The Spanish Bride in less than six months and with so much else going on in her life. The War had started but it would be several months before it began in earnest. It was during the quiet months of the “Phoney War” that Georgette finally managed to complete her latest novel. At first enthusiastic about the book and it’s prospects for serialisation and a large audience, by late September Georgette had grown pessimistic about the novel’s prospects:

I don’t think, in any case, it’s a suitable subject for present conditions, but I’m too tired & dispirited to think of another. I suppose I shall have to try & finish the book, & must start night-work again. It won’t be ready for anything earlier that January publication, if that. I wish some German would come & drop a bomb on me. It would solve all my problems.’

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 24 September 1939.

Her depression did not last, however, and by November she wrote cheerfully to Moore about a delightful lunch given for her at Heinemann’s headquarters at Kingswood in Surrey. It may have been at Frere’s instigation that the heads of Heinemann played host to Georgette and took such enthusiastic interest in her latest novel. Frere has begun to more fully appreciate Georgette Heyer’s value to the firm; he also understood her better than anyone. Frere knew that she felt undervalued and the lunch was an early step in redressing this and in meeting her author needs. Georgette thoroughly enjoyed the event and told her agent that:

‘I lunched at Kingswood yesterday, & you’ll like to know that C.S. [Evans] was present, & that we got along very well, though it was tacitly accepted that Frere has the handling of my work. But the party – Evans, Frere, Oliver, Hall, & myself, was most cheery, & everyone was flatteringly full of interest in the Smiths. I took Harry with me, in the shape of his autobiography, & was urged by Frere to find, & read to C.S. his description of his wife: “when I was first troubled with you, you were a little, wiry, violent, loving, ill-tempered, always faithful little devil” This was a riot with the firm. […] Frere was in great form. He suddenly demanded: “How long is it going to be? 120,000” I told him not to be funny, & that it would be more like 200,000, so he instantly said: “Oh, that’s all right! Then we’ll publish at 18/6, my dear, & make a real noise about it!” We had some hot arguments, of course. I told him some time ago that Wellington was making a nuisance of himself, & trying to steal the stage, & his view is that I’ve no business to interfere with him, & why shouldn’t he have the stage anyway? But as this leads to increased length I am suppressing his lordship. [Arnold] Gyde wants a wrapper by the Infamous Army artist, of the drumhead wedding, so we spent some time over costumes, & studied pictures & things. You see how seriously it is being taken!

Georgette Heyer to LP. Moore, letter, 16 November 1939

In the last week of December 1939, Georgette sent the final chapter of The Spanish Bride to be typed. Once she had the complete manuscript before her, she corrected it and sent it to Heinemann for typesetting. By 4th February 1940 she had almost finished correcting the proof pages and was pleased to find that “the timing is good. Nor is it, as I feared, just one dam’ battle after another.” She had loved writing Harry and Juana’s story and confessed to feeling bereft when it was finished:

‘When Harry set sail for Bordeaux, I felt as miserable as he did. I removed from the book-rest on my table, Vol VII of Oman, Vol VI of Napier, Bardacher’s Spain & Portugal, Fortescue’s maps, & Larpent’s Journals., & felt I was parting from old friends. But the book-rest still holds Kincaid, Simmons, Leach, Surtees, the Life of Colborne, the Waterloo Roll Call, a Spanish dictionary, & Oman’s Wellington’s Army. You note that Smith himself is not included. He always lies open on the table, like my volumes of historical notes.’

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 13 December 1939.

NB It was probably through Sir Charles Oman that Georgette obtained access to Sir George Scovell’s personal diaries, for Oman was the father of Georgette’s lifelong friend, Carola Oman, and had himself referred to Scovell’s papers when writing his multi-volume History of the Peninsular War. In 1930 Oman had donated some of Scovell’s papers to the National Archives but it is not clear what happened to the diaries after Georgette finished writing The Spanish Bride.

7 thoughts on “The Spanish Bride – history brought to life”

Thank you for such a revealing post on The Spanish Bride. Shines a light on Georgette Heyer’s meticulous research and personality – much appreciated!

I’m so glad you enjoyed it, Ann. It’s a pleasure to be able to use some of my research to expand on information in my Heyer biography. Thanks for taking the time to post.

This is fascinating, Jen. After reading it years ago, I read Harry’s autobiography and was struck by how closely Heyer kept to the story, even the dialogue was familiar. Theirs is one of the great love stories, I think, outlasting both their long lives. Not well known but inspiring, especially when you consider how young she was and he not all that many years older. Love all the letters to Heyer’s agent. They provide a great insight into her thinking.

Thank you Elizabeth. I’m really glad you enjoyed it. Warm wishes, Jen

In the 1960s, I was at teacher training college, where we had to do several weeks’ teaching practice as part of our course. One of them was in Wisbech (Cambridgeshire) which I really enjoyed, partly because of its connection to Harry and Juana Smith, of ‘The Spanish Bride’ They were, of course, real people, and several schools are named after Harry Smith, who was a local boy! Wisbech is very proud of Harry Smith! I was pleased to think that thanks to Georgette Heyer, I knew quite a lot about Harry Smith. I loved thinking of Harry and Juana living in that Fenland town. I wonder if Juana found the flatness of the Fens very strange?

I fell for Harry and Juana after reading ‘The Spanish Bride’, so when I was sent from my teacher training college in Saffron Walden (Essex) to Wisbech(Cambs) to do my Year 2 teaching practice, I was thrilled to be in the home territory of Harry Smith himself! (and Juana!). Several schools and other places are named after Harry; they are very proud of him. I loved it there; it was so pleasant that I nearly enjoyed my Teaching Practice!

A very belated reply due to website issues but thank you for posting Rachel and what a lovely story. I can well understand how you fell for Harry and Juana, but how delightful to have been in his home territory. I’m glad it eased your journey through Teaching Practice! Thanks again, Jen