“Georgette Heyer was a stern realist. She wrote romantic comedies, entertainments set in the Regency period in England, when women concentrated entirely on the essential business of getting married, hopefully for love, preferably with rank or money attached. Immersed in the world Jane Austen – for whom similar considerations ruled the day, influenced, too, by Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, Georgette Heyer was also a fine Regency scholar. Her novels are a meticulous recreation of that world of manners down to the smallest detail of social code, dress, food, conveyance and language.

Carmen Callil and Colm Toibin, The Modern Library: The 200 Best Novels in English Since 1950, Picador, 1999.

“It’s about Sophy that I’ve come to see you”

“As a matter of fact,” said Sir Horace, shutting his snuff-box, and restoring it to his pocket, “it’s about Sophy that I’ve come to see you.”

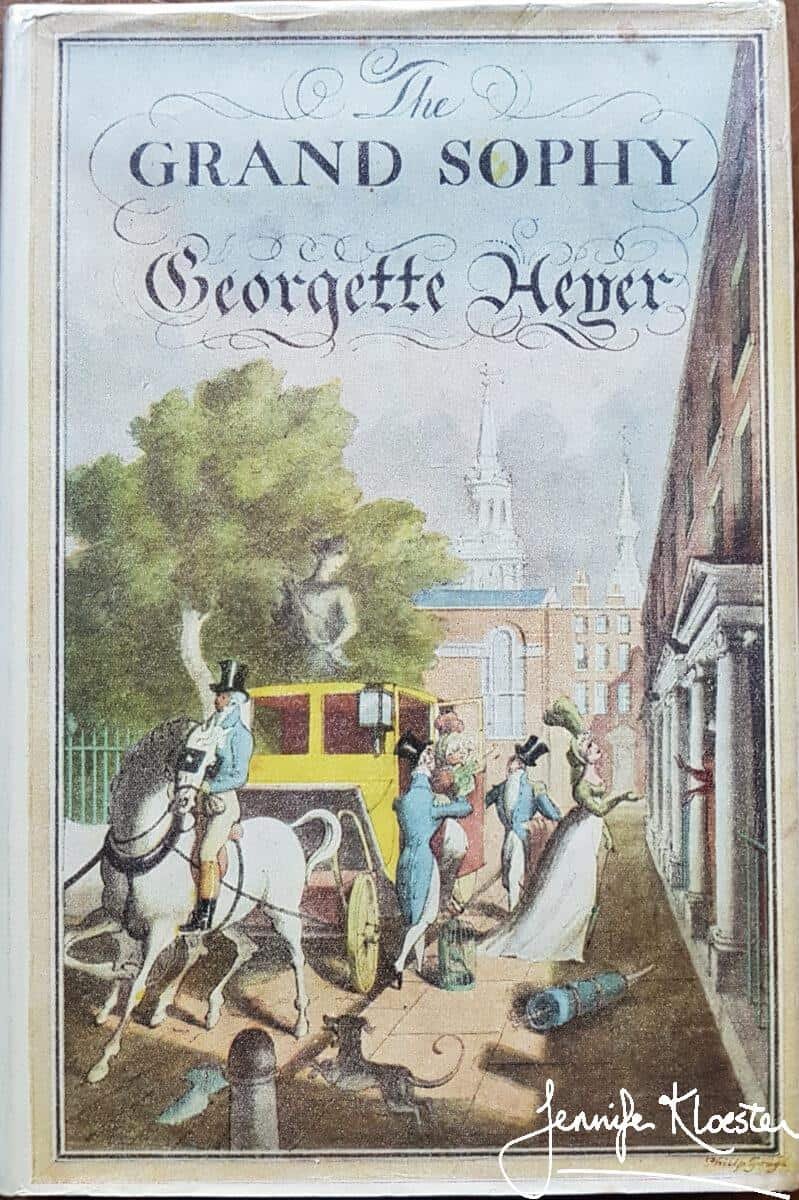

Georgette Heyer, The Grand Sophy, Heinemann, 1951, p.3.

It is here, with Sir Horace’s first mention of his daughter, that the reader is introduced to one of Georgette Heyer’s best-loved and most formidable characters. Growing up motherless, under the aegis of her intelligent, worldly father, Sophy has enjoyed an unusual childhood. She has known a degree of independence unfamiliar to most women of her age, class and time. In a world where little is expected of women beyond domesticity and child-bearing, Sophy has a different perspective. Being female is no barrier to Sophy’s many plans and ambitions. She is not only above the average height, she is also of above-average intelligence and is far more worldly-wise and experienced than most of her female peers. She has spent years in her father’s train, even accompanying him to the Peninsular where she experienced both privation and adventure. Sophy is equally at home on horseback, in the ballroom, the sickroom, following the drum or in diplomatic circles. Perhaps as a consequence of this rich and varied experience she has developed an acute understanding of human nature. She is acute and perceptive and, as the novel shows, she can assess in a moment the true state of a relationship. Frank, honest, intelligent, far-sighted and kind, from her first entrance – complete with horse, monkey, parrot and dog – to her final exit amidst ducklings, absent-minded poet, harassed Spaniard, and happy lovers – Sophy carries the novel and everyone in it.

Charles, Sophy & Eugenia

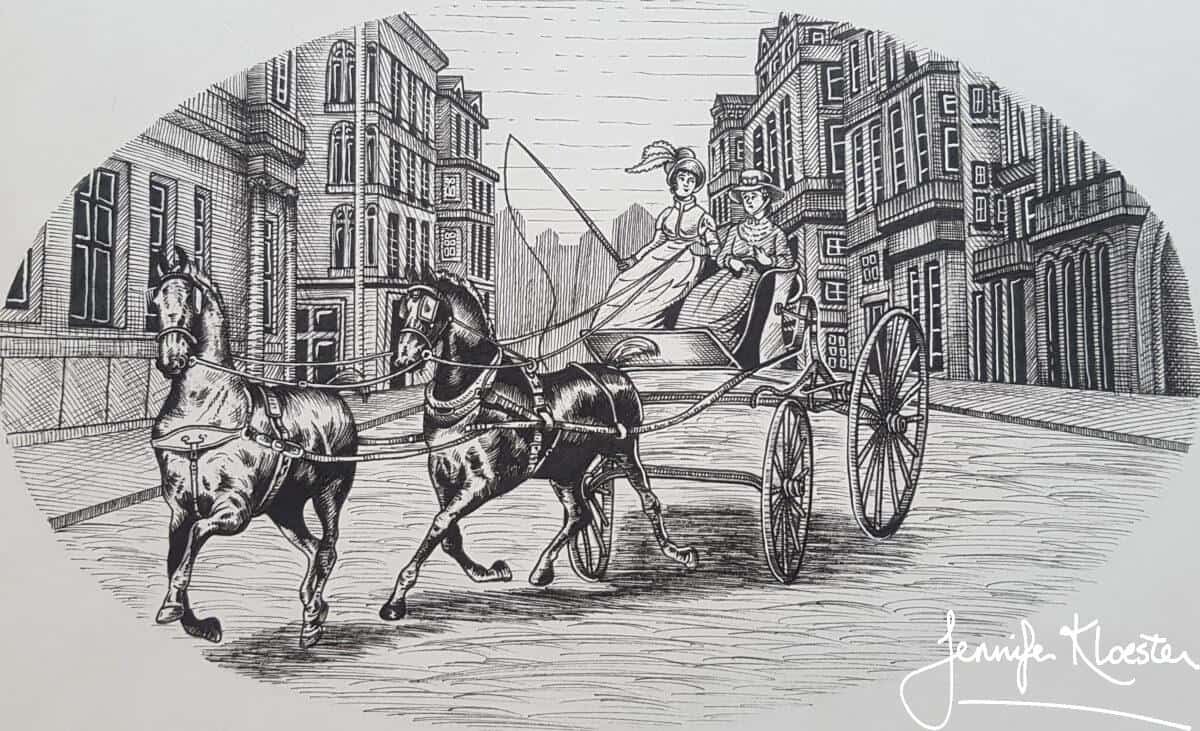

On arriving in London to stay with her uncle and aunt, Lord and Lady Ombersley, Sophy takes in at a glance the true state of unhappy affairs in the Ombersley household. Almost immediately clashing with her disagreeable cousin, Charles, Sophy soon learns that his (at times) surly demeanour is not without just cause. Charles is beset by responsibility: his father is a profligate who has gambled away too much of the family’s fortune leaving it to his son to provide for the children. Charles’s sister, Cecilia, on the brink of an advantageous marriage to the attractive and congenial Lord Charlbury, has instead developed a penchant for the vague and impecunious (but beautiful) poet, Augustus Fawnhope (such a wonderful name!). As if these challenges were not enough to make him a bit difficult, in a moment of stress, Charles has also become engaged to the pious, straitlaced and unlikeable Eugenia Wraxton. Eugenia permeates the book with her Puritan attitudes and her sanctimonious demeanour. Every Grand Sophy reader loves to loathe Miss Wraxton and she is the source of one (among many) favourite scenes in the Heyer canon. Miss Wraxton is one of those people who holds herself in high esteem, believing that she is always right and that her view of the world is the only correct one. On an outing in the park, Eugenia takes it upon herself to not only tell Sophy how she should behave in London society, but also to warn her that her behaviour has already made her look “a little fast”. Eugenia then adds fuel to the fire by informing Sophy that her own (Eugenia’s) character “is sufficiently well-established to make it possible for me to do–if I wished–what others might be imprudent to attempt.” This galling remark is enough to prompt Sophy to impulsive action (having warned Eugenia that she might do so) and she sets her horses (driven tandem – see the picture below) trotting in the direction of St James’s Street so that she might fulfill an ambition and see all the gentlemen’s clubs. As she explains to the outraged Eugenia:

“Of course, I should not have dared to do it without you sitting beside me, to lend me credit, but you have assured me that your position is unassailable, and I see that I need have no scruple in gratifying my ambition. I daresay your consequence is great enough to make it quite a fashionable drive for ladies. We shall see!”

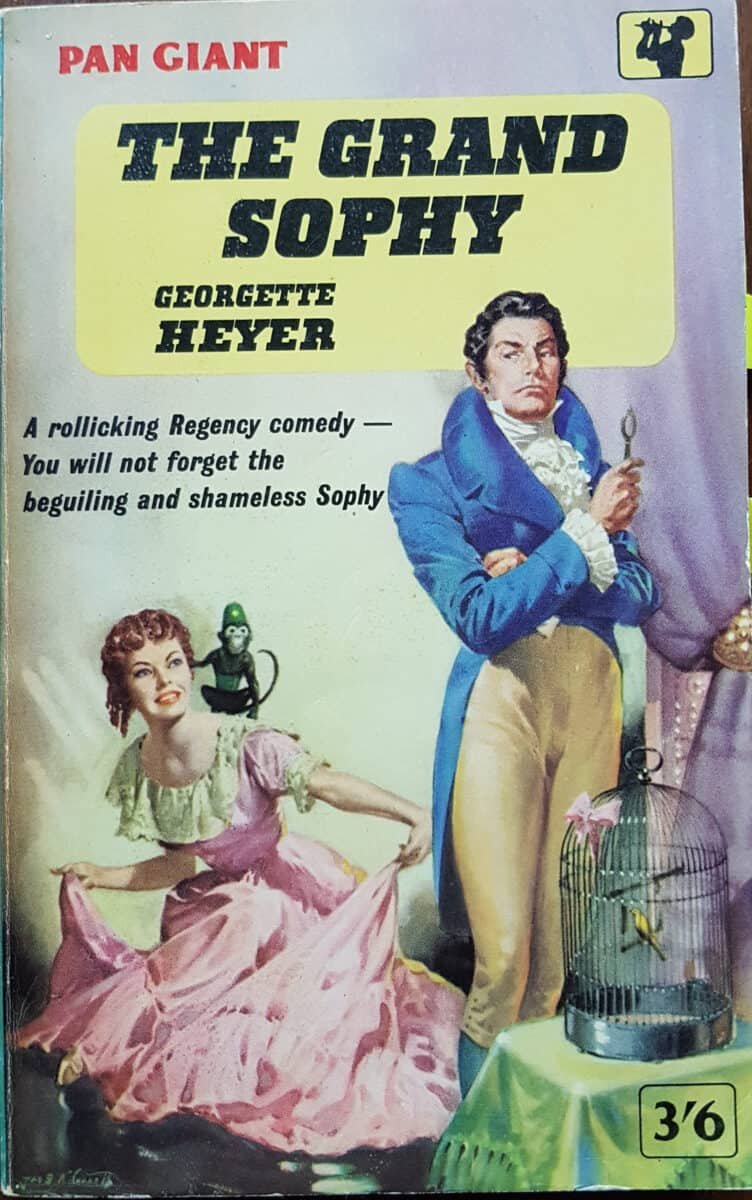

Georgette Heyer, The Grand Sophy, Pan, 1960, p.114.

Inspiration from Austen’s Emma

While the idea of a strong-minded female protagonist bent on organising and improving other people’s lives draws inspiration from Jane Austen’s Emma, Sophy Stanton-Lacy and Emma Woodhouse are very different. This is typical of Georgette Heyer. She so greatly admired and respected Austen that whenever she drew on any aspect of Austen’s work – language, character, class distinction, plot point – Heyer made sure she did not copy her literary idol. In The Grand Sophy Heyer created a feisty heroine whose judgement does not err; in Emma we have a heroine whose many errors of judgement become the force by which she learns to know herself. Sophy, however, already knows herself; it is those around her who must come to understand and – for the most part – appreciate the accomplished person that she is.

Sophy herself, an independent creature of charm and spirit and more of an intriguante even than Emma Woodhouse, sets the Ombersley household by the ears from the moment of her arrival. She is more successful and enterprising in her match-making (and breaking) than Emma, and the fact that this usually tiresome habit does not seem tedious to the reader is due to Miss Heyer’s skill in delineating character, for her Sophy is refreshingly charming, and if she is sometimes a little too resourceful and accomplished to be true she is always entirely natural. The other characters are equally alive and all are entirely credible.

Patrick Thursfield, The Times Literary Supplement, 3 November 1950, p.689.

More to Charles Rivenhall than meets the eye…

It is not only Eugenia who is discombobulated by Sophy’s honest responses to things, Charles too is also unused to having his authority (as he sees it) challenged. Least of all by a woman and even less by a woman with such an abundance of confidence and ability as his cousin Sophy. But there is more to Charles Rivenhall than at first meets the eye. Sophy, more than able to stand up to him, gradually learns (like Elizabeth Bennett) that first impressions are not always correct. The first clue comes from Charles’s way with animals. An animal lover herself, Georgette Heyer always regarded animals as excellent judges of character and more than once she used them to indicate a character’s worth or likeability. Sophy is surprised when her shy Italian greyhound, Tina, shows Charles affection and trust. Further affirmation of her difficult cousin’s true nature comes from his friend, Cyprian Wychbold, who tells Sophy that: “Thing is, he’s got an awkward temper, but he’s a dashed good friend! … the fact is, ma’am, that there’s no one I’d liefer go to in a fix than Charles Rivenhall.” One of Georgette Heyer’s great talents was for creating characters that evolve and change over the course of the novel. If at first, we do not warm to Charles, by the end, like Sophy herself, we too have discovered his acute intelligence and the depth and strength of his character.

“The last part of the book”

Kind, generous and loving, Sophy is also a pragmatist. Wherever and whenever she sees a problem, she also sees a solution and almost immediately sets about doing whatever it takes to implement it (even if it means shooting someone!). Managing people is as meat and drink to Sophy and if her solutions are sometimes outrageous, she nearly always achieves her goal. The Grand Sophy is a novel replete with memorable characters, including Charles and Eugenia, Cecilia, her poetic swain, Augustus Fawnhope, the disreputable Sir Vincent Talgarth, the remarkable Spanish lady, Sancia, the Marquesa de Villacanas, and, of course, that prosy bore, Lord Bromford. It is a testament to Heyer’s remarkable talent that she was able to bring all of these disparate characters together for an extended final scene that must be among the funniest in literature. She had begun to develop this latent skill in some of her earlier novels but it bloomed into full flower in The Grand Sophy. In a scene set in a dingy mansion replete with ducklings, she sets about resolving every conflict, breaking and making matches and setting all to rights. In a marvellous imbroglio ending every character gets his or her just deserts and the final encounter between Charles and Sophy is eminently satisfying. The ending of The Grand Sophy is a master-class in literary stage-management and ranks among her best finales.

“The resolution of such predicaments was always Heyer’s subject matter; her originality lay in the precision and charm of her writing style and in her taste for the wit and frivolities of the period. She was phenomenon. Widely imitated, within the genre of romantic comedy she was unequalled, and one of the best entertainers of her time

Carmen Callil and Colm Toibin, The Modern Library: The 200 Best Novels in English Since 1950, Picador, 1999.

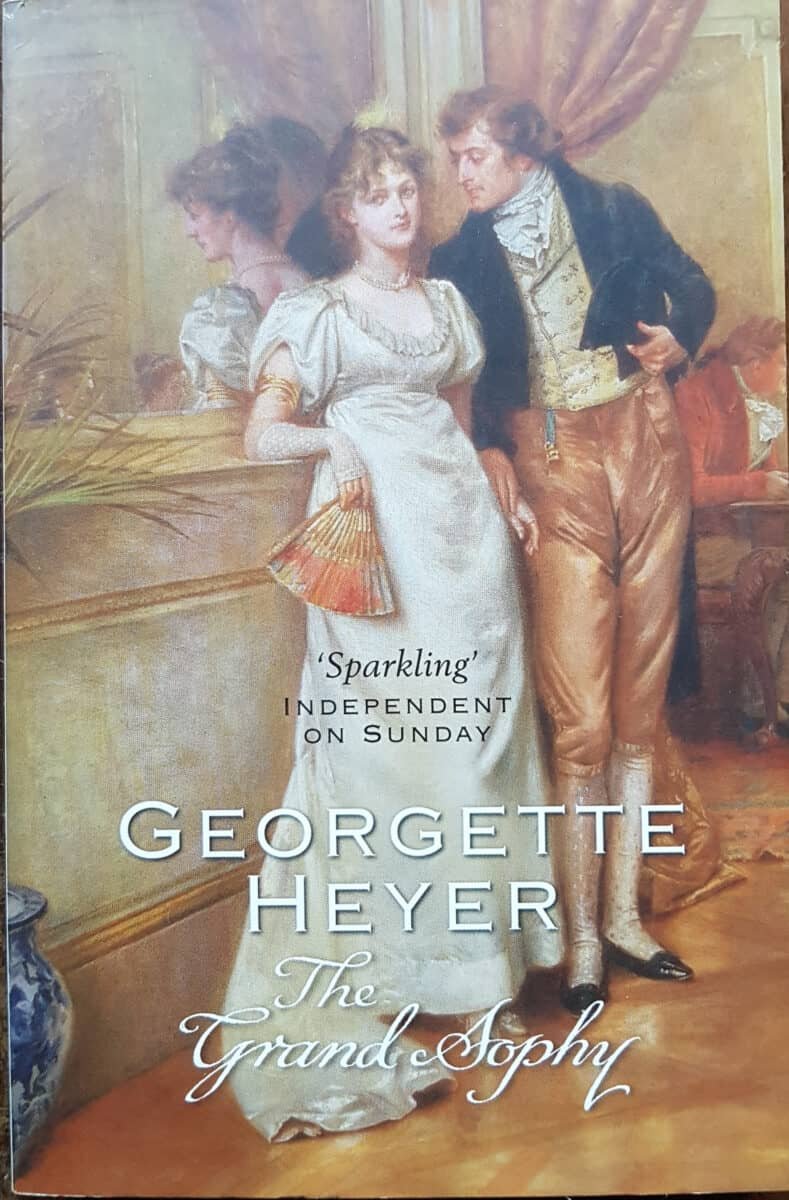

The 2006 Arrow edtion of The Grand Sophy

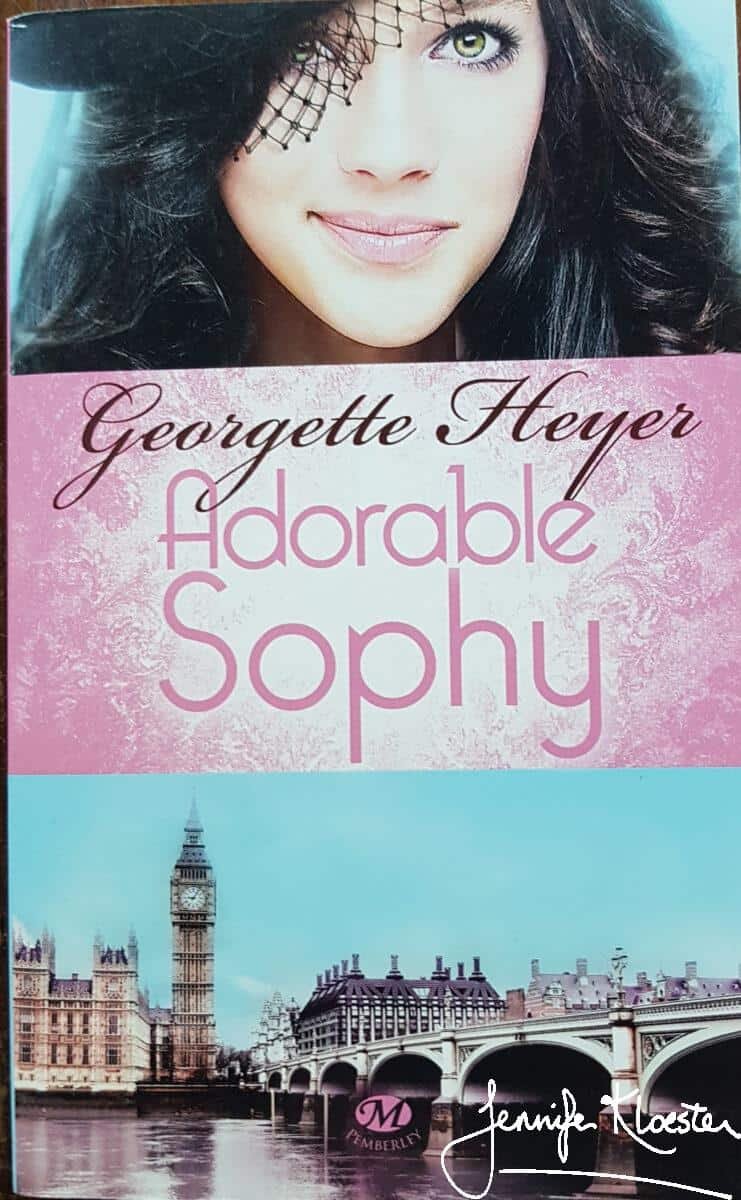

The 2012 French edition of The Grand Sophy

“So The Grand Sophy is your favourite”

It seems amazing that Georgette claimed to being bored while writing The Grand Sophy! Even going so far as to say that she had “bought a large bottle of disinfectant” – apparently because she thought that the novel “stinks”. Her brother, on the other hand, “thought it most amusing” and an American fan so much enjoyed the book that she wrote to Georgette in 1969 to tell her so. Alhough the author’s reply reflects her by-then habitual self-deprecation, Georgette does allow a hint of self-praise to peep through! But she was never one for “puffing off her consequence”! She must have thought the fan letter intelligent, however, for she wrote back to say:

Your letter, for which many thanks, has been forwarded to me from Albany, where, indeed, I did live, until two years ago. I can’t tell you how much I am gratified to learn that I am a good influence on the modern Young! I feared that I was a very bad one, for several girls of my acquaintance have turned down eligible suitors, because they are none of them at all like Heyer-heroes—!! It never seems to occur to these damsels that no one could possibly live with a Heyer-hero — if any such man existed, which I doubt! So The Grand Sophy is your favourite! Oddly enough I wrote that book with large tears of boredom running down my cheeks, I only warmed to the job when I got to the last part of the book — which I do think quite good! I have a theory that what bores me to write will bore other people to read, but I see that I must be wrong, for a great many people like Sophy much more than my own favourites amongst my own works! Again thanking you for your letter,

I am

Yours sincerely,

Georgette Heyer

Georgette Heyer to Mrs Meursinge, letter, 23 July 1969.