“I am now about to perpetrate another piece of nonsense, so that for the first time in my life I shall have something up my sleeve. I rather want to call it Snowbound, but as I’m still uncertain about the plot this isn’t yet decided. As a preliminary, I’ve dug up a lot more Regency slang, some of it very good indeed, and the best quite unprintable.”

Georgette Heyer to Roland Gant, editor at Heinemann, letter, 15 May 1956

“Snowbound”

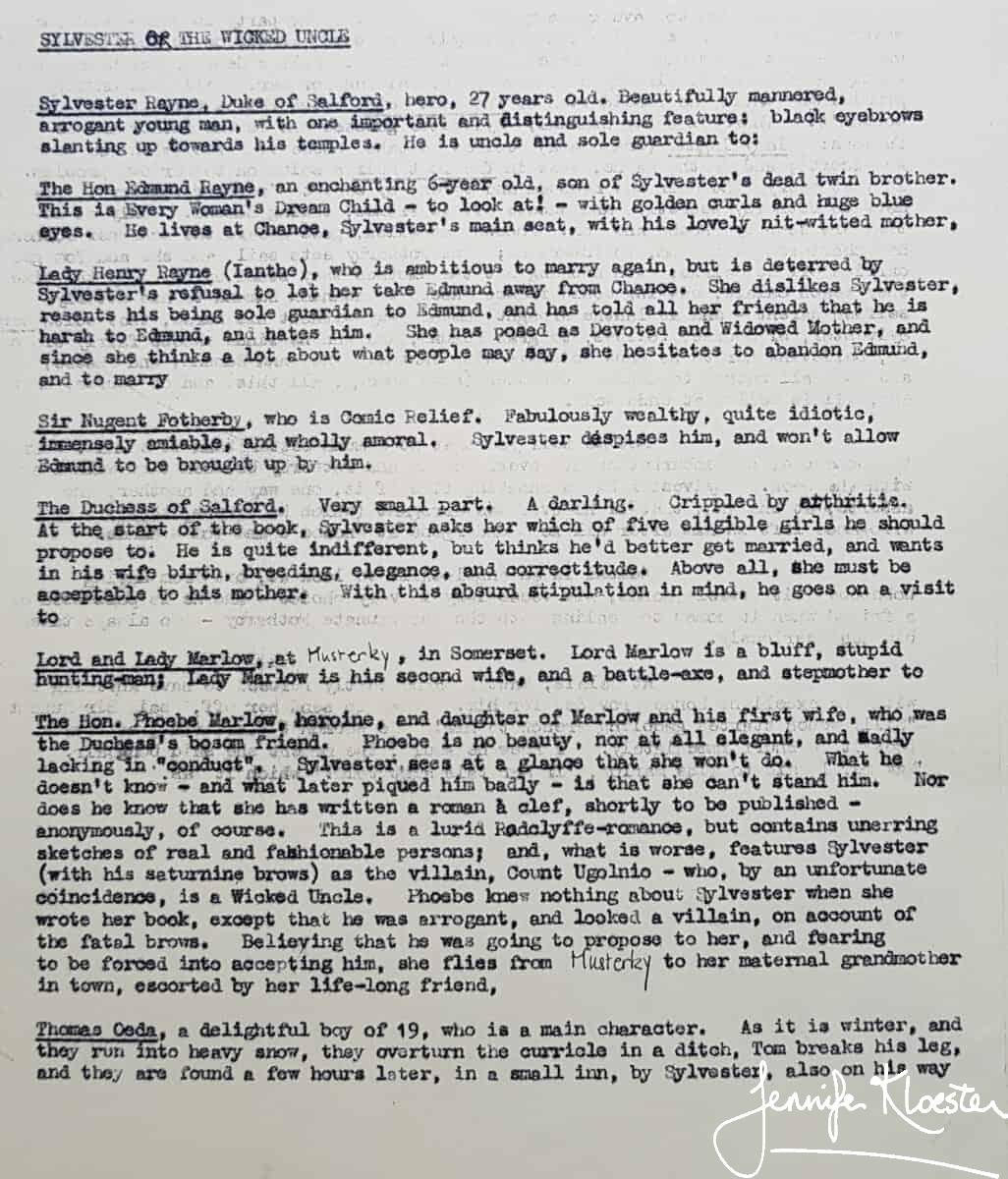

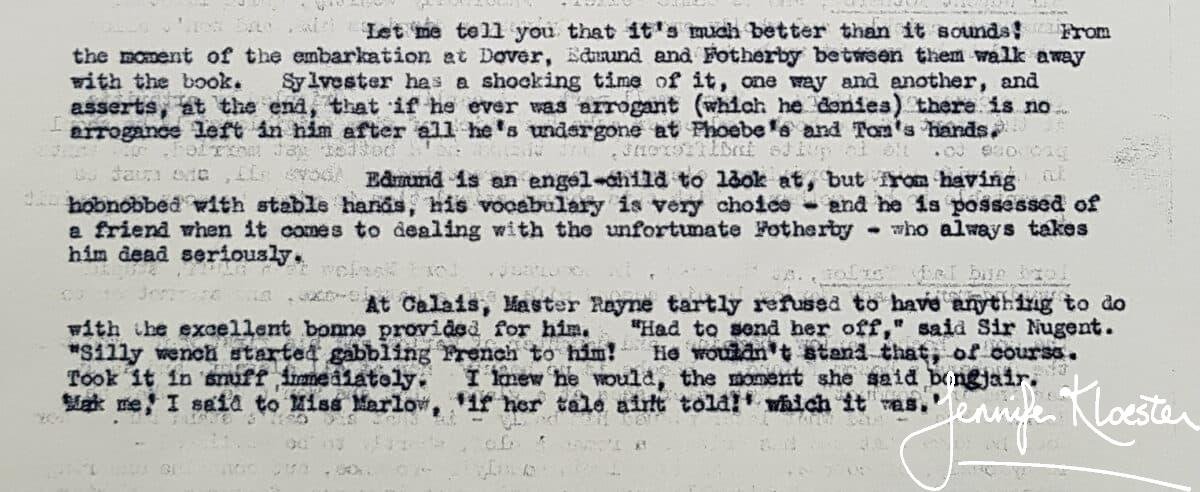

Georgette Heyer’s forty-fifth novel was begun late in December 1955. Originally intended as a short story called “Snowbound”, Georgette began writing it in response to a request from the editor of Everybody’s. This popular magazine was keen to emulate the success of Woman’s Journal which always sold out whenever they published anything by Georgette Heyer. Georgette had written about 8,000 words of “Snowbound” when she “had a change of heart at 11.45 last night, [and] decided it wouldn’t do”. She put the manuscript aside and instead began writing a new short story entitled “The Necklace”. This, like “Snowbound”, was destined never to reach Everybody’s nor to remain as a short story. By May 1956, Georgette had turned “The Necklace” into a new Regency novel, which she called April Lady. That novel came out in January 1957, by which time she had finally started writing the novel inspired by “Snowbound”. The new title was Sylvester or The Wicked Uncle and by mid-March she had written just over 60,000 words. Unusually for Georgette, this time the writing had been what she considered slow going due mainly to several bouts of ill-health. As she explained to her publisher and friend, A.S. Frere:

“I have been ill for the past month, & have only just resumed work on Sylvester – & slowly, at that. For the past ten days, I have typed, laboriously, about half a page a day. However, there were signs yesterday of lubrication, & I even felt a stir of interest – which is heartening. I don’t like to give you any hard date, because it has now happened twice that when I thought myself restored to health I have suffered a relapse – or developed a fresh ill. I suppose it would be unreasonable to suppose that after 28 days of what Jane Austen would call “a putrid sore throat” I should, at my age, recover in a flash. Foolish persons keep on urging me to go away for a Nice Rest, & a Change of Air; but only Ronald took No for an answer, understanding that to go away, leaving a book on the rocks, would fret me into my grave. There are times when I quite like that man. I aim now at May – or the end of April.”

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 16 March 1957.

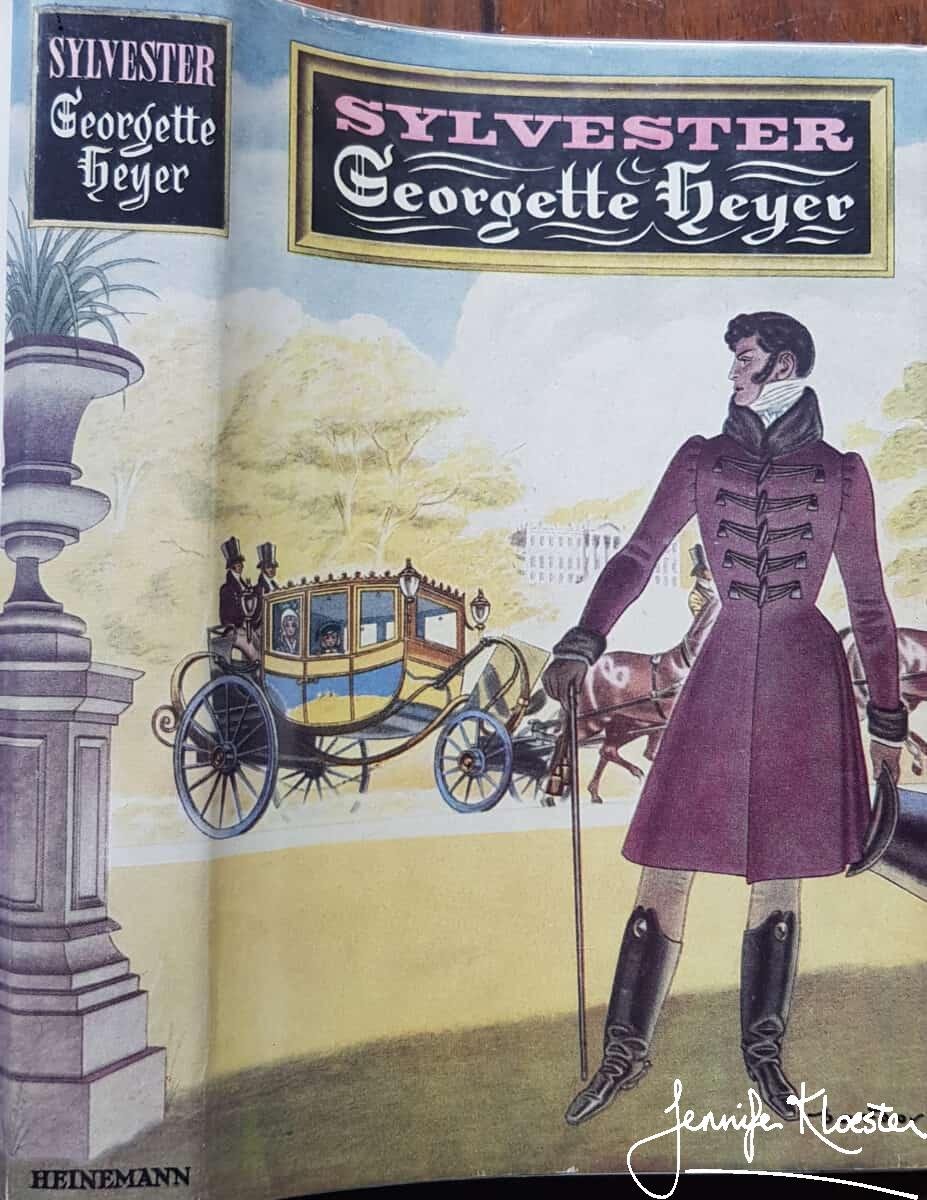

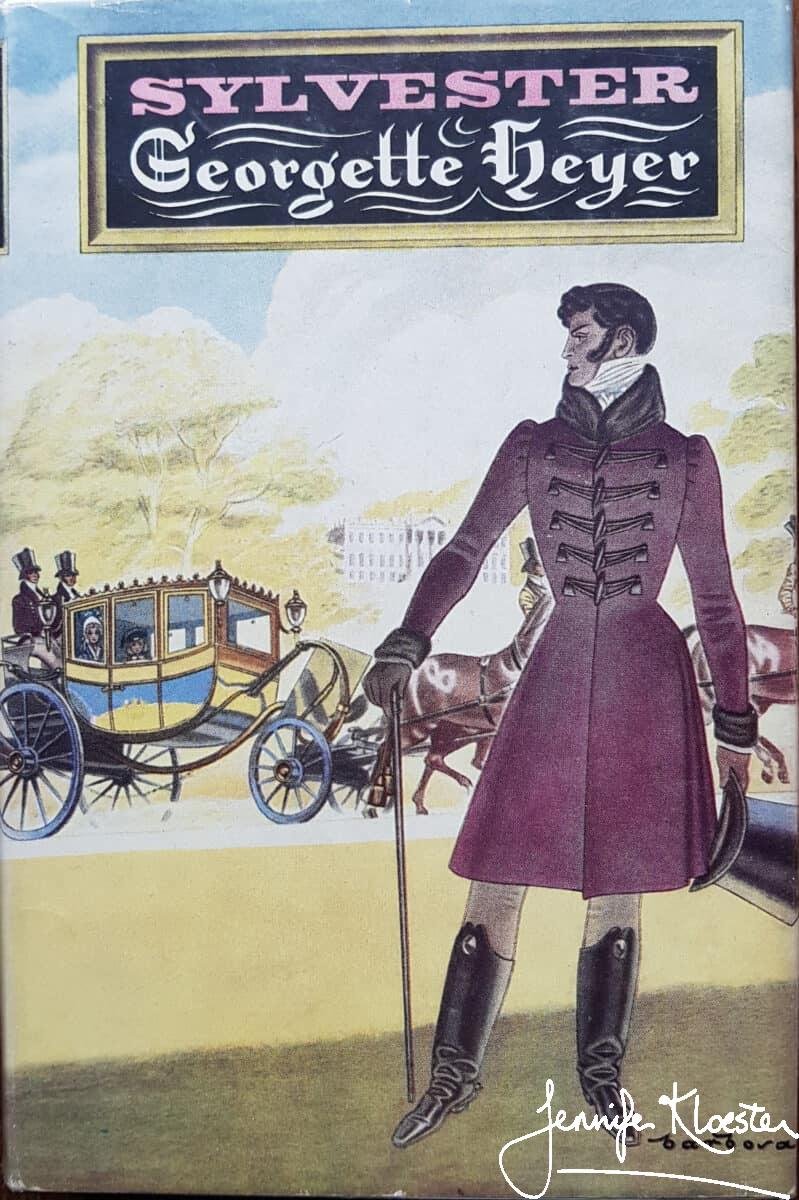

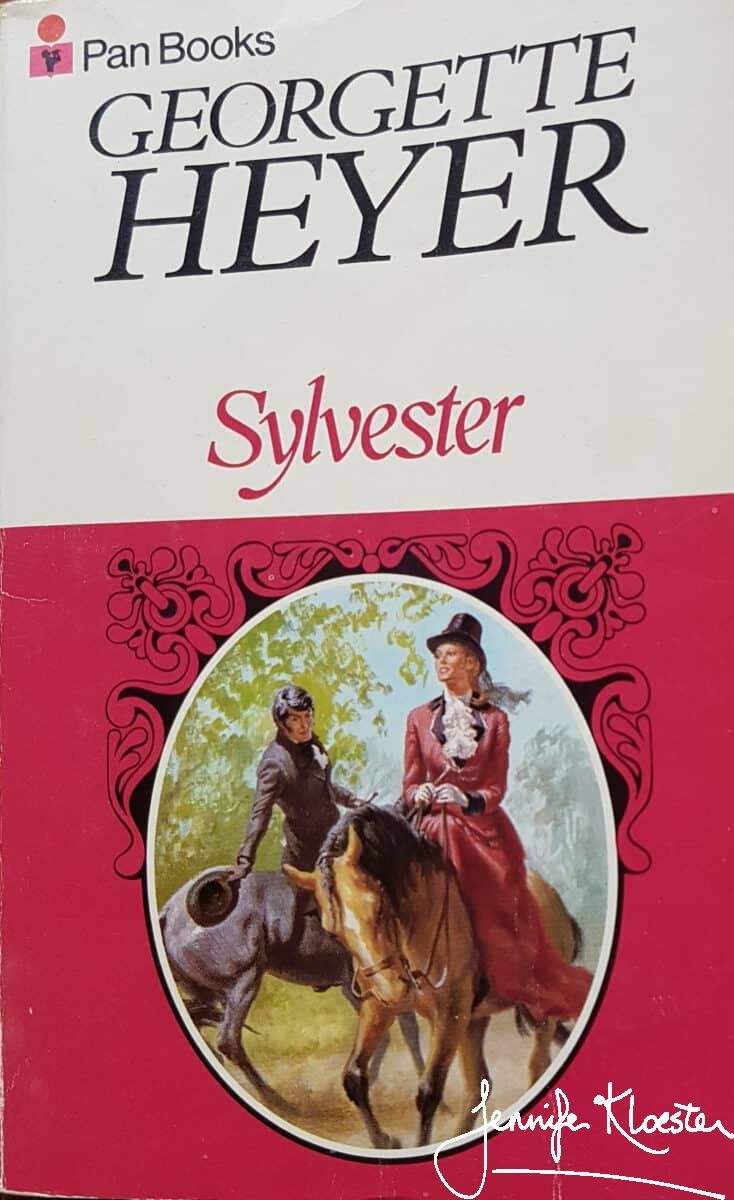

One of the 1970 Pan editions of Sylvester.

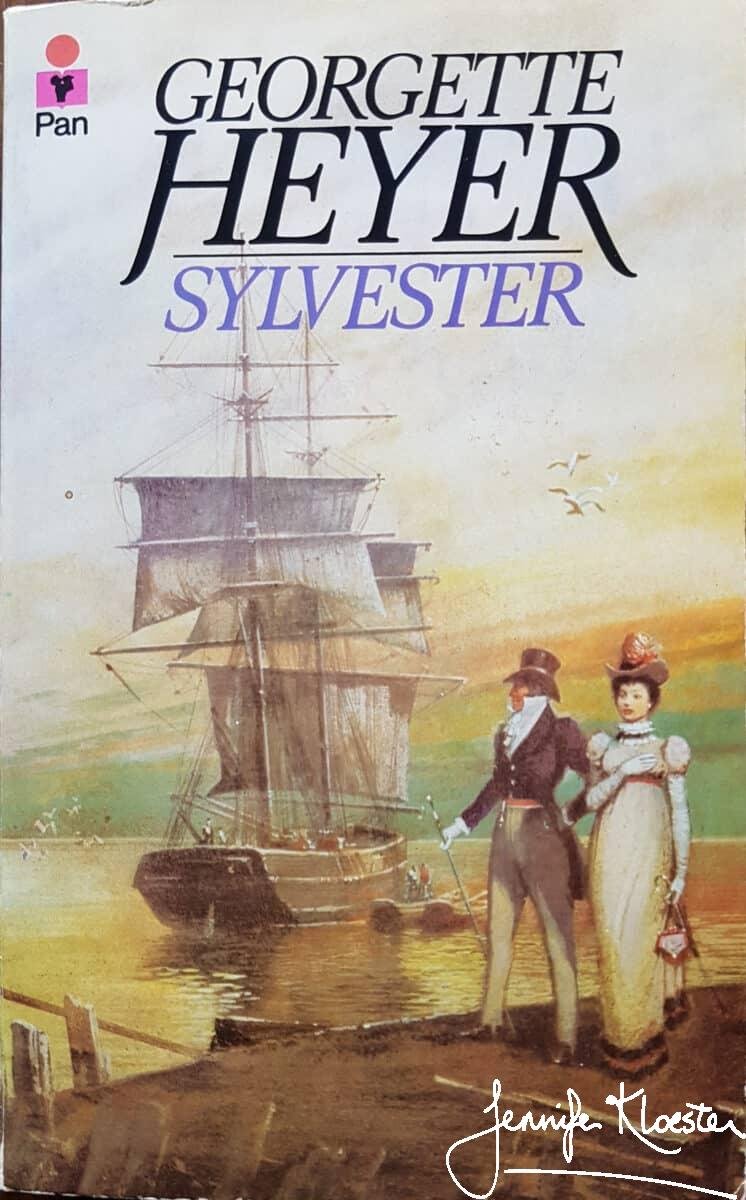

The second 1970 Pan edition with an elegant cover depicting Tom and Phoebe on the dock at Dover.

Pride and prejudice…

The Austen reference seems particularly apposite as, reading Georgette Heyer’s delightful comic Regency, Sylvester, it is clear that she was inspired in part by Jane Austen’s iconic novel, Pride and Prejudice. In both books, misunderstanding begins with the hero’s pride in his lineage, his estates and his connections – all of which cause him to put a value on his own worth far above that of the heroine’s. She, in her turn, is prejudiced against him because of what she perceives to be his arrogance. In spite of himself, the hero becomes intrigued by the heroine and is piqued when she rejects him. There are many Austenesque moments in Sylvester and, as always, Heyer took care never to copy her adored Miss Austen but put her language and phraseology to good use. When Mrs Orde, the Squire’s wife, “paid off every arrear of a debt of rancour” to Lady Marlow, the Austen reader is reminded of Caroline Bingley who “paid off every arrear of civility” to Elizabeth Bennet. In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs Bennet foretells her daughters’ unlikely marriages to wealthy men; in Sylvester his mother foretells his unlikely match to Phoebe, the daughter of her dearest friend when, in response to Sylvester’s idea that “mothers always made marriage plans for their sons!”, the Dowager Duchess tells him that the “only marriage I ever planned for you was with a three-day infant, when you were eight years old!” Towards the end of the book, Sylvester makes Phoebe a proposal of marriage that is almost as bad as Darcy’s first proposal to Elizabeth. And at the very end, when Phoebe’s satirical suggestion that she should write a second novel and dedicate it to Sylvester prompts him to suggest that she could include a “pompous epistle”, the reader is reminded of Austen’s reluctant dedication to the Prince Regent in Emma – a decidedly pompous inclusion written for her by her publisher. In writing Sylvester Georgette created a story utterly unlike Austen’s in terms of plot and characters, but the Austen influence is unmistakeable and the novel is richer for it.

Sylvester

Sylvester’s starting premise is a simple one: at the age of 27, Sylvester Rayne, Duke of Salford, has decided he must marry. As a man “endowed with rank, wealth, and elegance” he believes that he has the pick of the debutantes and that no woman would ever think to refuse an offer from him. Sylvester has even “more or less” made out a list of the qualities he considers “indispensable” in his future bride. He relates this list to his intelligent, poetess mother, who is not only startled to find her adored son so coldly pragmatic in matters of the heart, but also shocked to discover that he cannot imagine any female to whom he might make an offer rebuffing him. She finds no comfort in her sister’s pronouncement that “He knows his worth too well!” Heyer’s depiction of Sylvester is masterful and her hero’s encounters with first his mother and then with his godmother, who also happens to be the heroine’s grandmother lay the foundation for all that is to come. Here is a man so sure of himself, so well set-up in life and yet so utterly unaware of his arrogance and self-consequence that it requires a woman utterly unlike any he has yet encountered to open his eyes. One of the joys of the novel is manifested in the various ways in which Sylvester is forced – mainly by Phoebe Marlow’s candour and propensity for getting into scrapes – to confront his pride and his prejudices and become a better man.

Phoebe

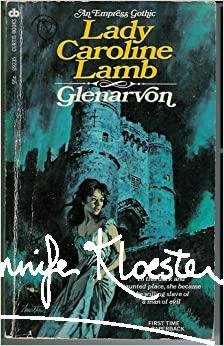

It is not only Sylvester who must confront his prejudices, but also the heroine, Phoebe Marlow. Phoebe, too, is blind to the depth of her own prejudice. Bullied by an unloving and dictatorial stepmother, during her first London Season the year before the story begins, Phoebe’s fear of rebuke rendered her colourless and unmemorable. Unfortunately, Sylvester was among those who passed her over and, inspired by his arrogance and his flying, saturnine eyebrows, she has cast him as the villain in her first novel. A keen observer of human nature , with a talent for mimicry, Phoebe’s novel The Lost Heir is a roman à clef. As with Lady Caroline Lamb’s actual novel, Glenarvon, Phoebe has written about real people and events – all of which she has thinly disguised in her fictional story. Sylvester, of course, knows nothing of Phoebe’s novel and nor does anyone else in London. In keeping with the tradition of the time her book published anonymously – by “A Lady” – but when it is an instant bestseller, all of society become agog to know the author’s identity. From here, Georgette leads her readers into a merry tangle of confession, retribution, remorse and restitution.

Glenarvon and The Lost Heir

In 1816, Glenarvon created a sensation for its portrayal of many of society’s most notable people. Caro Lamb cast her former lover, Lord Byron, as the villainous Lord Glenarvon, and also included the Patronesses of Almack’s Club as characters in her novel. The lady Patronesses’ outrage at being thus portrayed ensured that Lady Caroline was banned from Almack’s for a time because they were so offended by the book. Of course, in Sylvester, Phoebe’s roman à clef is a novel within a novel, though it, too, portrays real people – including the Patronesses – behind a fictional facade. As always with Georgette Heyer, there are layers within layers and there are many enjoyable parallels between Phoebe’s The Lost Heir and Glenarvon. Both are wildly melodramatic and improbable tales that not only won for their authors fame and fortune but also caused them great trouble and distress. Phoebe’s singular sin in writing The Lost Heir, however, is to have portrayed only one character as being without virtue and that is her villain, Count Ugolino, who, with his flying eyebrows, is instantly recognisable as Sylvester! It is Phoebe’s prejudice against the man she believes Sylvester to be that impels her to run away from home rather than receive an offer of marriage from him. And it is in unexpectedly catching up with her that Sylvester and Phoebe, with Phoebe’s lifelong friend, Tom Orde, become snowbound at a rustic inn. This was the basis for the original short story. The entertaining scenes at The Blue Boar allow both hero and heroine to begin the process of overcoming both their pride and their prejudices. Ironically, by the time Phoebe’s novel is published, much of her prejudice against Sylvester has dissipated and they have become friends. Thus she frets over the novel and longs to tell him what she has done but is frightened of the likely consequences. The remainder of Sylvester includes one of Georgette’s most brilliant imbroglio endings replete with high drama and perfectly-executed comedic scenes.

P.S. Georgette, the young writer:

In addition to the clever plot, compelling characters and ironic comedy, Sylvester has the added benefit of offering readers some delightful parallels with Georgette Heyer’s own writing life. When she describes Phoebe Marlow’s early promise as a writer it is not hard to see Heyer’s own story in the description:

“From the little girl who scribbled fairy stories for the rapt delectation of Susan and Mary [Boris and Frank], Phoebe had developed into a real authoress, and one, moreover, who had written a stirring romance [The Black Moth] worthy of being published.”

Georgette Heyer, Sylvester, Pan, 1970, p.48.

“It had come white-hot from her ready pen, and Miss Battery [Georgette’s father] had been quick to see that it was far in advance of her earlier attempts at novel-writing [Georgette wrote stories from an early age]. Its plot was as extravagant as anything that came from the Minerva Press; the behaviour of its characters was for the most part wildly improbable [The Black Moth]; the scene was laid in an unidentifiable country; and the entire story was rich in absurdity. But Phoebe’s [Georgette’s] pen had always been persuasive, and so enthralling did she contrive to make the adventures of her heroine that it was not until he had reached the end of the book that even so stern a critic as young Mr Orde bethought him of the various incidents which he [like most readers] saw, in retrospect, to be impossible.”

Georgette Heyer, Sylvester, Pan, 1970, p.48

“Miss Battery [Georgette’s father], a more discerning critic, recognised not only the popular nature of the tale, but also the flowering in it of a latent talent. Phoebe [Georgette]had discovered in herself a gift for humorous portraiture…Miss Battery knew that it was these swift, unerring sketches that raised The Lost Heir [The Black Moth et al] above the commonplace. She[George Heyer] would not allow Phoebe to expunge one of them, or a line of their wickedly diverting dialogues, but persuaded her instead to write it all out in fairest copperplate [exactly as Georgette had to prior to submitting The Black Moth to Constable].”

Georgette Heyer, Sylvester, Pan, 1970, p.49.

High comedy

“She handles a plot and character with the nonchalant skill of the Four-Horse Club tooling match-bays around the park.”

Cover quote, Pan, 1970.