“On the road to White Ladies”

Georgette began writing her new historical novel in the spring of 1938. It was not an easy time in Britain, for the storm-clouds of war were gathering and rumour and uncertainty were rife. An eager reader of The Times, Georgette kept abreast of the political situation and she and Ronald undoubtedly discussed the government’s approach and, in particular, the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement. They were both conservative in their politics and in their daily lives, but Georgette was not convinced by Chamberlain’s pronouncement in September 1938 that he had achieved “peace in our time”. Given her awareness of the tensions in Europe it is not surprising that the three historical novels she wrote between 1936 and 1939 were about war and that each were strongly nationalistic and favoured Britain and its monarchy. An Infamous Army had been about the British victory at Waterloo and she now decided to re-tell the story of Charles II’s escape from Cromwell’s England after the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Charles II was the monarch about whom she had originally written in 1922 in her post-Restoration novel, The Great Roxhythe. The new book was to be set nearly twenty years earlier than Roxhythe and this time the king would take centre stage. Once again, Georgette read avidly and set herself the task of visiting every house and inn at which Charles had rested or hidden during his perilous flight to France. In April she ended a hasty letter to Moore with: ‘No time for more. On the road to White-Ladies, & the dawn at hand.’ It was to White-Ladies Priory that Charles II had been guided after the Royalist defeat and where he had been sheltered after the battle.

No Cromwellian

Georgette was no Cromwellian and throughout her life she held to the belief that the Royal Stuarts were the true kings of England and that the Hanoverians were, if not usurpers, at least intruders. She was extremely annoyed when Queen Elizabeth II named her firstborn son Charles, given that it was a Stuart name, and the Windsors were descended from the German Hanoverian kings. Still, these were trivial matters, and once she began writing the new novel, Georgette quickly became immersed in the sources. She called the book Royal Escape and in her usual meticulous fashion not only visited every inn connected with King Charles’s escape, but also took copious notes from books borrowed from the London Library. Her research notebook shows how she drew the details of the King’s journey from the different primary texts, writing them down in parallel columns and annotating as she went. She worked hard on the novel which took her almost four months to write and produced, if not a riveting tale, at least a worthy one.

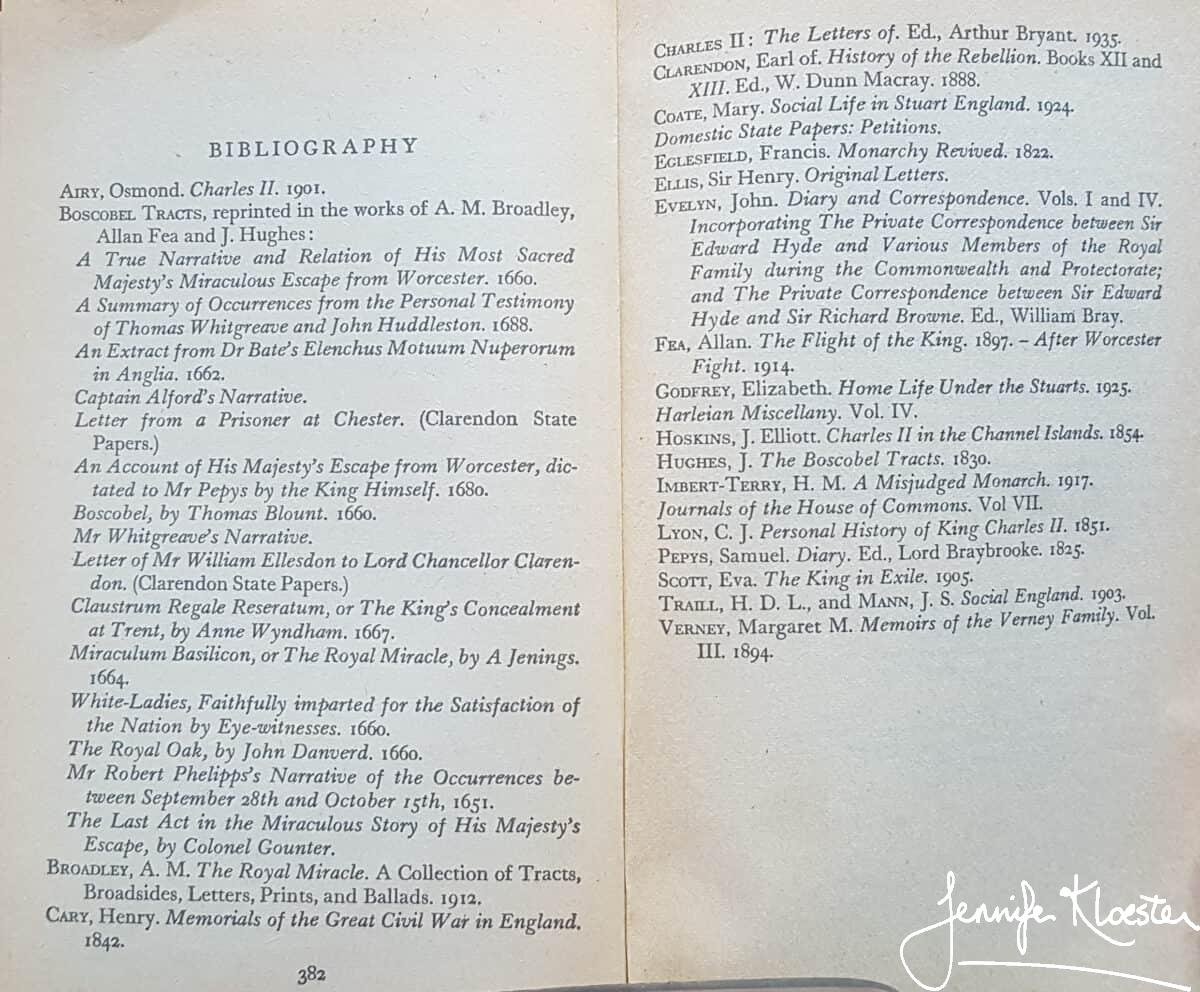

A bibliography

Royal Escape is not without its fast-faced, compelling scenes; the characterisation is good and the language feels authentic and this is due to Heyer’s diligence in reading as many of the firsthand sources as she could. Royal Escape is one of the rare Heyer novels that includes a bibliography so it is easy to see from where she drew her period language and the details of her story. It is a detailed story – perhaps too detailed – for Heyer tracks the King’s journey from Worcester to White Ladies, to the Penderel’s, the Royal Oak, Wales and Bristol and all the places in-between as though she were afraid to leave anything out of such an important historical story. She makes a good fist of the material and at times the novel is well-paced and interesting; the King’s reactions to his trials and tribulations are clearly depicted, but there is something lacking in the overall effect. Jane Aiken Hodge in her 1984 biography of Heyer offered a perceptive account of the novel’s challenges:

‘in the main she was inhibited by the very richness of her sources. She puts a ripple of amusement into the King’s voice from time to time, but cannot bring him to life. Partly because of the limitations imposed by the plot, there is a failure of tension in Charles’s relations with the people around him

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Pan, 1985, p.59

“Immense fun”

There is no doubt that Heyer enjoyed researching and writing Royal Escape and years later, Sylvia Gamble, the young woman who had been employed to type up An Infamous Army, reported that she and Georgette had had “immense fun” driving around the countryside in pursuit of all the places in which the King had hidden during his escape from Cromwell’s army. By the time she had finished the novel, however, Georgette had begun to have doubts about Royal Escape and in a letter to her agent expressed the hope that it ‘will not be a long, dull book! You never know – perhaps continual travel & escape becomes boring’. Heyer was perceptive but, while some readers agree with her assessment of the novel, the critics of the day were more flattering. When Royal Escape came out in America in February 1939 it was warmly received with enthusiastic reviews in The New York Times, The New Yorker and The Saturday Review, whose critic declared that:

Miss Heyer is adept at giving full-bodied reality to such a story. Casual readers who know her only in another role and remember her only by such detective tales as They Found Him Dead will be prepared for the ease with which she develops her narrative, but they will be amazed at the learning which she displays so dexterously and so generously. She has taken her sources as seriously as would a professor of history, and has weighed all the evidence of those multitudinous tracts that, with the Restoration, celebrated Charles’s miracle.

Charles David Abbott, ‘King Charles on the Run’, The Saturday Review, 4 February 1939, p.7

On 5 October 1938, Georgette accompanied Ronald to London for the Bar exams. They stayed at the Waldorf Hotel and while Ronald attended the Inns of Court, Georgette arranged to have lunch on different days with Joanna Pullein-Thompson, her publisher Alexander Frere and her agent Leonard Moore. It was a welcome break from literary cares for she had been feeling ‘dreadfully depressed’ about Royal Escape. Although she had garnered several good reviews for the book in the British papers, she had not been pleased by what she felt was “a luke-warm review in the Times Lit. Supp. Written by a Cromwellian, I fancy”‘ But British sales for the book exceeded her expectations and in January 1939, Frere showed her ‘some nice-looking figures’. In its first three months Royal Escape had sold nearly 8,500 copies – 1,500 more than An Infamous Army and 3,000 more than Regency Buck – and the figure did not include the Christmas sales. Georgette would write one more book about war, The Spanish Bride but before that she would pen one of her funniest detective novels, No Wind of Blame.