Her death came as a shock

On 4 July 1974 famed author Georgette Heyer died. She was 71 and over her fifty-year career had written 55 novels and an anthology of short stories. At the time of her death she was selling a million copies a year in paperback and fifty years after her passing she is still selling. An international bestseller, her death came as a shock to her fans around the world and many of them wrote to her publisher at the Bodley Head to ask if there were any unpublished manuscripts among Georgette’s effects that might yet be put into print to delight her readers one last time. Sadly, there were no completed manuscripts – but there was one unfinished novel that, with some attention, could perhaps be published posthumously. The novel was My Lord John and this is its story.

RAISED ON SHAKESPEARE

Georgette Heyer was raised on Shakespeare. From an early age she engaged with the works of the Bard and as an adult found much to intrigue and inspire her in the plays known as the ‘Henriad’. These were the four plays about three of the kings of the great English Plantagenet dynasty (1154-1485): Richard II, his cousin, Henry IV, and his son, Henry V. It was this latter monarch which, in 1939, Georgette decided would make a fascinating subject for a new book. She had just finished The Spanish Bride, set during the Napoleonic Wars, while at the same time war was on England’s doorstep. Beginning with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany on 1 September, through the ‘Phoney War’ and into 1940 with the eventual overrunning of France and Belgium in May, inevitably war was paramount in people’s minds. To Heyer, Shakespeare’s Henry V probably felt relevant given that it is a story about war, patriotism, and immense courage in the face of overwhelming odds. It is also a play about an English victory which features Henry V’s famous ‘band of brothers’ speech with which the king ignites his troops before the Battle of Agincourt. There were literary riches to be mined here and Georgette wrote enthusiastically to her agent about her idea for the book. She was disconcerted, however, to received a less-than-encouraging reply. In mid-December 1939 she wrote back to Moore to say:

My dear L.P.! I do hope you will rid your mind of the idea that Henry V will be as faulty a work as the Conqueror! I never was more depressed than when I read your grim prophecy. And if it isn’t a damned sight better than the Army ( which has always filled me with a sense of satisfaction) it is time I packed up.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 13 December 1939

‘I HAVE LOVELY IDEAS FOR MY BOOK ON HENRY V’

Of course, Georgette Heyer would never have ‘packed up’ for she was a compulsive as well as a compelling writer (and The Conqueror was a masterly achievement) and she assured Moore that ‘I have lovely ideas for my book on Henry V. I think I shall call it Stark Harry.’ But her confident assurance did not play out as she had hoped. The book she was planning would prove to be a challenge unlike any she had yet or would ever encounter in her decades-long writing life. Throughout her career, Georgette had always written quickly and even in the last years of her life she was able to pen a 120,000 word novel in just a few months. The story of the Lancaster family, however would be different. At first, her focus was on Henry V and the book was to be called Stark Harry. Two years later – and most unusually for Heyer – she had written nothing of the new novel. Instead she had published two historical romances and a detective novel and was now immersed in Penhallow. In 1941 this was the book that obsessed her from the moment it had fallen fully-formed into her mind.

STARK HARRY STILL ‘PENDING’

She had not forgotten Henry V, however, for in February 1942, she wrote again to Moore to report that Frere had written to her to say that:

He will publish whatever I want to write, & thinks well of my suggestion that I should do something more worth while than these frippery romances. He says good books are selling better than bad ones, & tells me Macmillan has subscribed over 10,000 of Miss West’s new magnum opus! [This would have been Rebecca West’s non-fiction book, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, about the causes of the Second World War.] Isn’t that a cheering thought? Anyway, Frere says, Write what you feel like, & take as long over it as you want to, & throw off the ‘tec novel & the serial in between whiles. He says “you can do them on your head” – little recking that at the moment I couldn’t even do them the right way up. So it may well be that I shall have a stab at StarkHarry. What do you think about it? (Don’t you like the spurious diffidence with which I consult you & Frere about what I’ve really made up my mind to do anyway? But in these bad times I really would be amenable to reason, if you both advised me against any dire course.)

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, February 1942A month later Stark Harry was still ‘pending’ and the war was taking its toll. It may have been the harsh realities of the Second World War that caused Georgette to shelve her medieval book, but whatever the reason, it would be another seven years before she returned to the idea.

‘FETTERED EAGLE IS GOING TO BE GRAND!’

The War ended in 1945 and four years later, in April 1949, having finished another delightful Regency novel in Arabella, Heyer reported being ‘lost in the 15th century’. A month later, in the midst of various family issues and ‘general turmoil’, Georgette had managed to write enough of the new book to report that ‘Fettered Eagle is going to be grand!’ By now, her vision had enlarged and her focus was no longer solely on Henry V. Instead, she had decided to tell the story of the Lancaster family with Henry’s younger brother John as the main character. John was John of Bedford, the third son of Henry IV and the grandson of John of Gaunt, the first Duke of Lancaster and the founder of the Lancaster royal dynasty. John was an important figure in the era and Georgette had always felt that he should have been better known. In fact, her new novel was – in part – intended to change people’s understanding of this vital and influential period of English history. However, she also wanted to write a book that would make the critics and the academy sit up and take notice. The fact that by 1949 she had written thirty-five novels and that many of them had been highly regarded and praised on both sides of the Atlantic did not seem to resonate with her. Heyer wanted more. All her life she would suffer (as so many authors do) from an overt lack of belief in her own ability. If, underneath, she knew that what she wrote was good, it was not something she could or would openly accept – at least not without the corroborating opinions of those people who apparently ‘mattered’.

‘FORGET BARBARA CARTLAND’

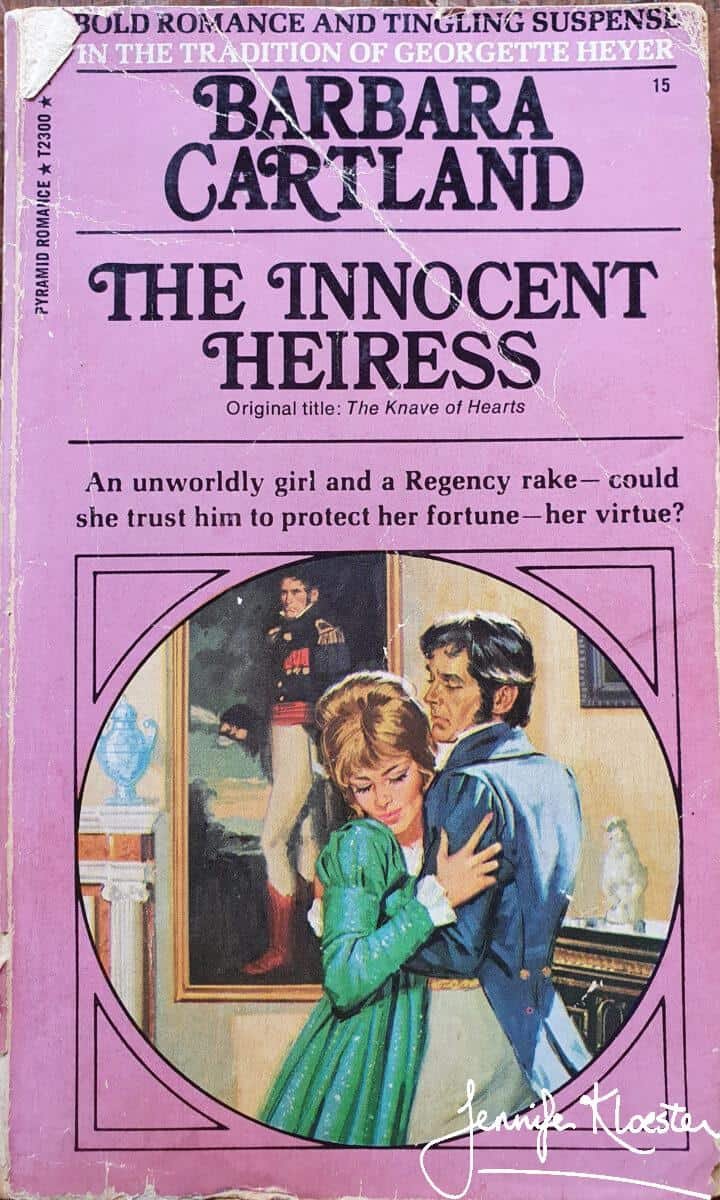

The new book was complex and, in terms of research, demanding. There were also other demands on Georgette’s pen for she could not afford to disappoint her eager public and forgo writing her annual novel. Having finished The Grand Sophy in the spring of 1950 she finally returned to her medieval novel. It was by now a whole year since she had told her publisher that Fettered Eagle is ‘going to be grand’ but she was at last immersed in the book she was now referring to as ‘Prince John of Lancaster’ and writing ‘Chapter 3 Beau Chevalier’. Unfortunately, she was fated to be interrupted again. This time she was disturbed by reports of plagiarism. A fan had written to tell her that an author by the name of Barbara Cartland had been ‘immersing herself in some of your books and making good use of them’. Georgette did not recognise the name but she certainly recognised the many ‘borrowings’ perpetrated by Miss Cartland when she read that author’s first-ever historical novel and its two sequels. A Hazard of Hearts, A Duel of Hearts, and Knave of Hearts, would consume hours of Georgette’s life as she cross-referenced the many ‘lifts’ (as she called them), between half a dozen of her own books and those comprising Cartland’s ‘Hearts’ trilogy. It was a frustrating episode and as Georgette explained:

a complete bore, and is wasting my time. Reading my own back numbers is Death – particularly when I’m at work on something quite different. Held up for a day, too, trying to get at the rights of a scandal about Bishop Beaufort.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore letter, 21 May 1950

Georgette tried hard to forget Barbara Cartland but it was difficult. As she told her publisher at Heinemann: ‘I can’t get the wretched business out of my head, and haven’t written a word of John for days.’

‘SHE WAS A PERFECTIONIST’

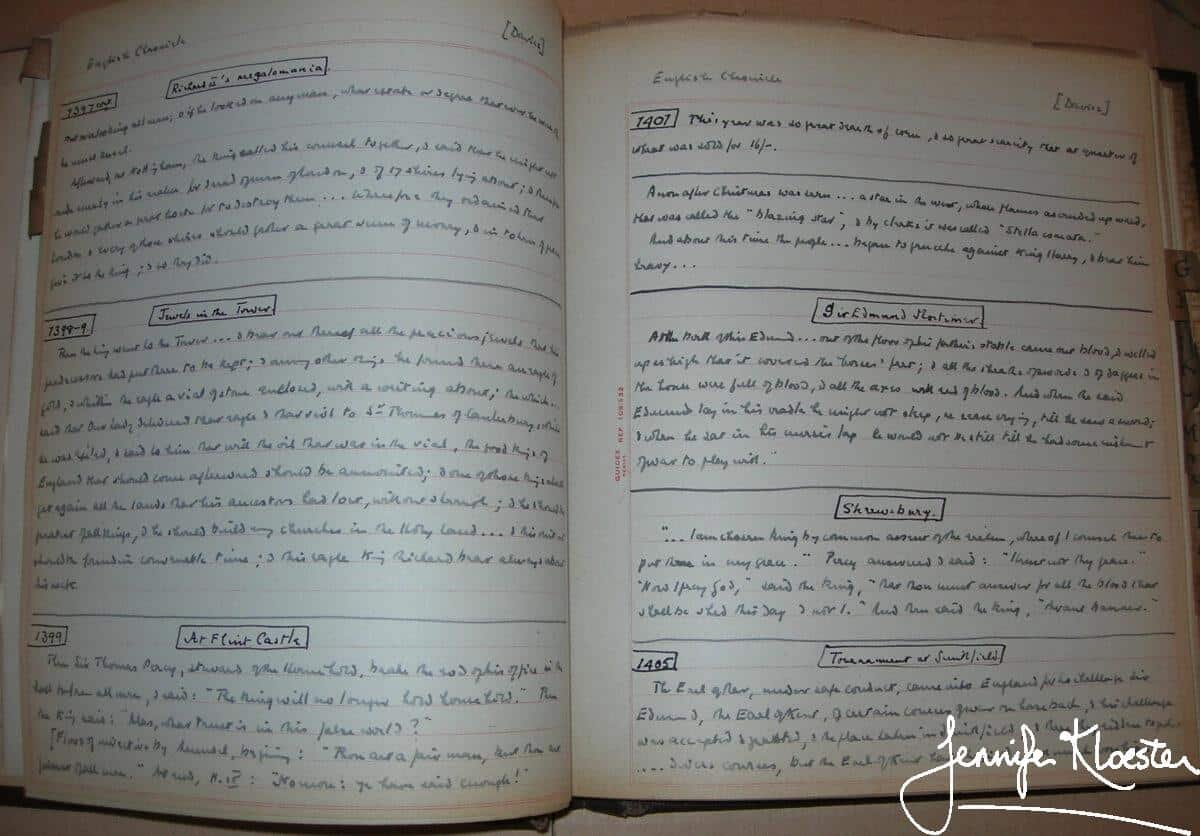

Eventually, Georgette was able to move on from the plagiarism affair and return to her medieval novel. It was an absorbing undertaking but one which – unlike her usual writing experience – took her far, far longer than perhaps even she had anticipated. She and Ronald had already visited France, there to see the site of the Siege of Orléans and John of Bedford’s tomb among other historic places of interest. She taught herself medieval English and took pleasure in deciphering early documents and garnering a large vocabulary. The following year, in the autumn of 1951, her novel took her to ‘the north country. A pious pilgrimage, in aid of my mediaeval book.’ Returning home, she triumphantly declared that she had ‘put no fewer than 12 ancient castles in the bag!’ And yet, once again the novel languished. It is perhaps not unreasonable to ask why it took Georgette Heyer – an author who was able to consistently write an enduring classic in only six weeks – so long to write My Lord John? It is Ronald who best answers the question in the Preface to the book which was eventually published the year after her death:

Her research was enormous and meticulous. She was a perfectionist. She studied every aspect of the period –history, wars, social conditions, manners and customs, costume , armour, heraldry, falconry and the chase. She drew genealogies of all the noble families of England (with their own armorial bearings painted on each) for she believed that the clues to events were to be found in their relationships… Her notes filled volumes. For the work, as she planned it, she needed a period of about five years’ single-minded concentration.

Ronald Rougier, Preface, My Lord John, Bodley Head, 1975

This was not to be given to her and, more importantly, it was not something she would ever take for herself – not even in the 1960s when her income was assured and she could have, if she had wished, given up writing Regencies and focussed solely on My Lord John. Perhaps it is here that the reason for this one unfinished novel lies. Perhaps, in her heart of hearts, Georgette knew that the task she had set herself was too great; that the book she had envisaged could not be written as her other books had been written –with a closely-knitted plot, wit, humour and sparkling dialogue. Nor could she create her usual cast of memorable characters, so that even the minor players remain with the reader long after the book is ended. She was shackled by history and by her long-held belief in the importance of facts. A close look at the novel itself is enlightening.

My Lord John

The historical tale was intended to be a grand one, full of twists and turns, battles and betrayals, plots, conspiracies, friendships, murders and beheadings, but its subject matter would prove to be too vast, even for so skilled an author as Georgette Heyer. And it was not only the breadth of the topic, nor the fact that Prince John’s life was, for its time, a long and complicated one. John’s story begins in childhood and carries through until his twentieth year, at which point Georgette ‘laid John of Lancaster in lavender’ and did return to him until just two years before her death. There is much in the novel that is worthy and plenty of scenes where Heyer’s inevitable talent shines through. The problem, in my estimation, is that the story has no clear overarching plot or climax. Even in her most serious historical novels such as The Conqueror, An Infamous Army, Royal Escape, or The Spanish Bride, Georgette was always driving towards a dramatic conclusion. Whether it be William’s coronation at Westminster, the breathtaking denouement of Waterloo, or King Charles II’s eventual escape to France, the action in these novels is constantly building towards an end-point. John of Bedford’s life – though full of interesting moments and events – is one of shift and change without an overriding tension to keep the reader going. He is a worthy figure, too, but, try as she would to make him live (and there are scenes where he comes splendidly into clear focus), Georgette could not give John the same sort of three-dimensional presence that she had always been able to achieve with the characters in all of her other books.

More historical narrative than novel

In part this was because My Lord John is more often a historical narrative than a historical novel. While the story is interspersed with vivid scenes of life, events and places, such as her description of Pontefract Castle where Richard II is said to have died, and there are moments of classic Heyer dialogue, the weight of history is a continual constraint. Unlike her other historical writing in this last book Georgette failed to wear her learning lightly but thrust medieval words and phrases into the text as if their mere presence would be enough to convince her reader of a fifteenth-century milieu. she was, of course, not a trained historian, but she sti took history very seriously. She believed in going to the sources, in finding the ‘facts’ and adhering to them as meticulously as possible. Her contract with her reader, even in her most lighthearted books, was that they could trust her history. Whether a modern historian would agree is irrelevant for it is what Heyer believed and it was upon that basis that she wrote her historical novels. My Lord John proved a difficult tale to tell because Georgette could not tell it with all of her usual verve and style. Inevitably, there was a large cast of historical figures to introduce to the reader, and perhaps, as in The Conqueror, this might not have mattered had she been able to offer her readers a strong plot with a clear beginning, middle and end. Instead, such was the diversity of people, essential historical moments needing explanation, and the impossibility of keeping her main character onstage long enough to establish him as someone for readers to care about, that it proved hard to hold the narrative together. Perhaps it was inevitable that the book would end by being uneven in both tone and intent. It seems likely that Georgette’s vision of the novel would never be met and she discovered this in the process of trying to create a compelling story out John of Bedford’s life story. She was a highly intelligent person and a truly gifted writer with a remarkable instinct for what worked in a novel. She must have seen – must have known – that this book, this one book out of so many, was never going to work. And so, she never finished it.

Perhaps Jane Aiken Hodge said it best:

‘Unfinished, her medieval project was at once a splendid hobby and a claim to the respectability denied to ‘mere’ entertainers. Finished it might have proved a sad disappointment.’

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, The Bodley Head, 1984, p.78

‘It is definitely GOOD, Max!’

It was to be many years before Georgette finally returned to My Lord John. Just eighteen months before her death she re-read what she had written and was moved to write to her friend and publisher, Max Reinhardt to say:

‘I got out my unfinished medieval book, and ever since have been toying with the idea of bringing to an end, with the death of Henry IV. For it is definitely GOOD, Max! When I read it, after heaven knows how many years, and when I had largely forgotten it, I found it absorbingly interesting!!! But it is not in my usual style, and I can’t make up my mind whether to publish it or not. I think I must be guided by you, and (if you can be bothered with it) mean to send you the three completed parts. The third is still unfinished, and I shall have to put in a lot of work, mugging up the sheaves of notes I took for it. But it you think it would be disastrous to publish it – well, I’ll still finish it, but will then put it away to be published after my death!’

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 27 November 1972

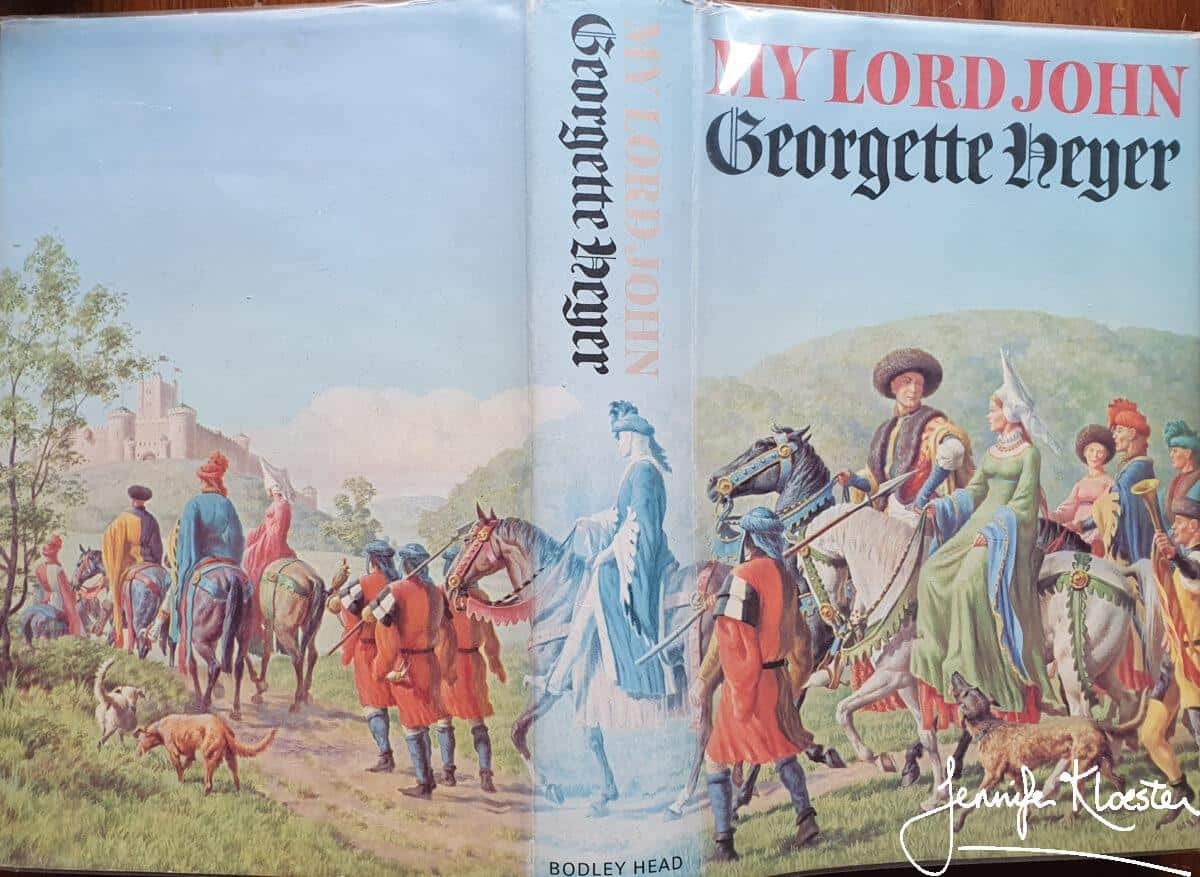

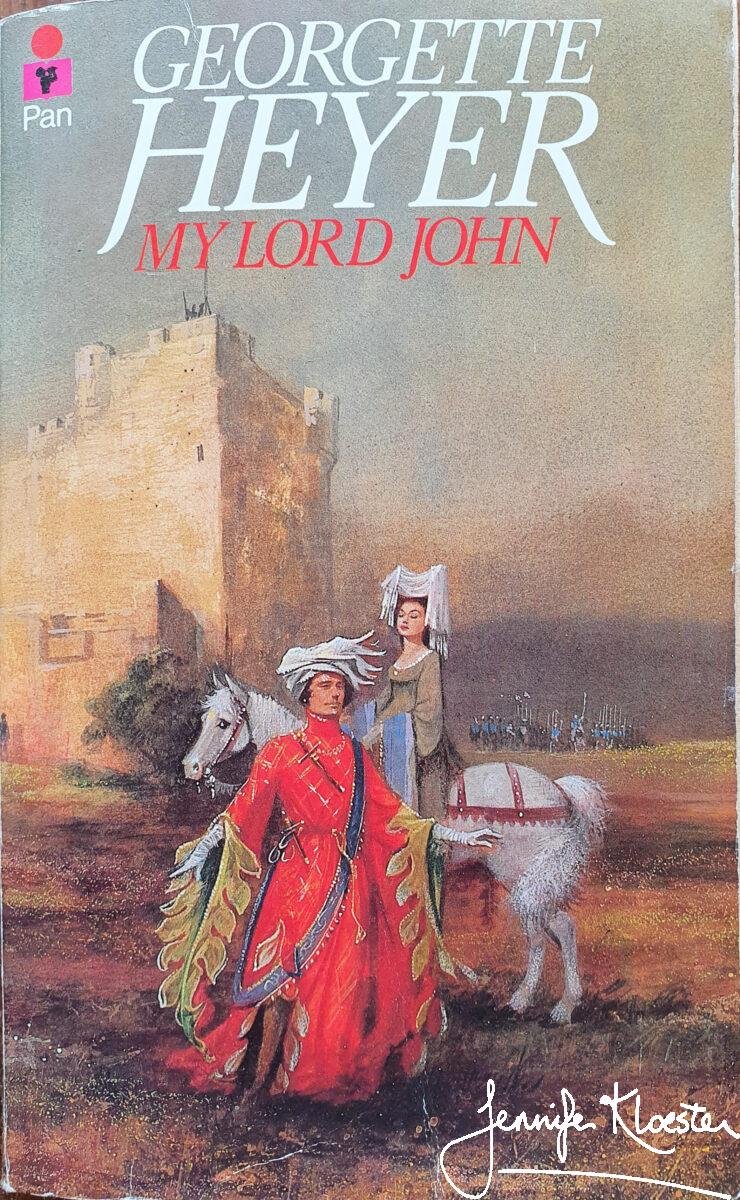

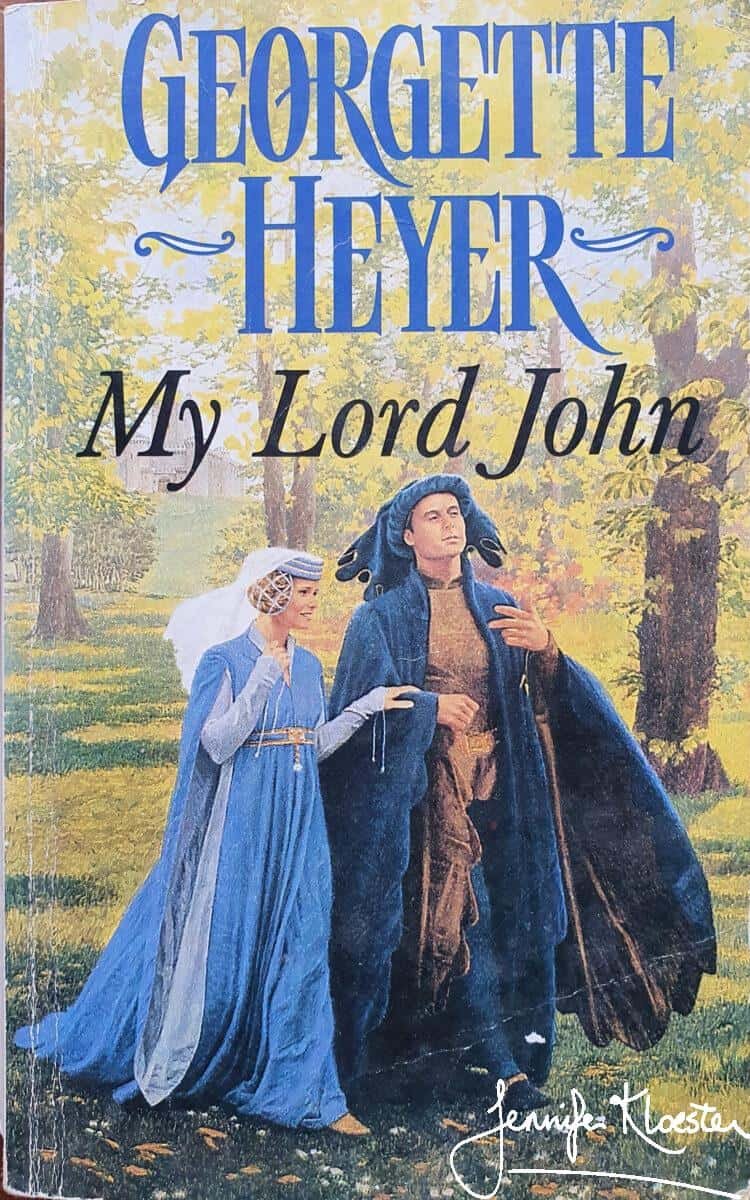

In the end, her wish was fulfilled and My Lord John was published the year after her death. It sold in large numbers and was extensively reviewed wherever it was published. Without exception all of her reviewers praised her research, her knowledge and her skill as an outstanding storyteller, but the majority view was that My Lord John did not match the standard set by her Regency novels. For Georgette Heyer was, above all, a master of comic irony and her most beloved books are a mixture of brilliant wit, vivid dialogue, memorable characters and ingenious plot given to the reader on page after page of perfect prose. In My Lord John the opportunity for these things was decidedly limited by the facts of history. The scope was too huge, the characters too disparate and the timeline of John’s life too fragmented for her to create her usual brilliant, cohesive story. The book will always be readable, but for most of Heyer’s readers it will never be a favourite. Although some people consider it to be among her best books, most find My Lord John to be a candle when compared to the shining light of her other books. I think she knew it, but she held on to her medieval dream until the end.

3 thoughts on “My Lord John – The One Unfinished Novel”

Sorry to be picky, Jennifer, but Henry IV was a cousin of Richard II who usurped his throne – for good reasons but with disastrous outcomes. Richard had no children of his own.

You’re not at all picky! I’m most grateful and will fix the error. Thaks so much for posting.

Thanks.