Georgette Heyer’s second contemporary novel, Helen, would also be her most autobiographical. She had struggled to write after her father’s sudden death in June 1925 and given up any thought of writing a ‘period’ novel. Though she loved writing historical fiction – especially the high-spirited, vivid novels with which she was making her name – Georgette needed to be in a positive frame of mind to do so. This eluded her for many months after her father’s death. When she did at last return to her writing, it was to pen the book that would be her most cathartic and her most revealing; years later she would firmly suppress it.

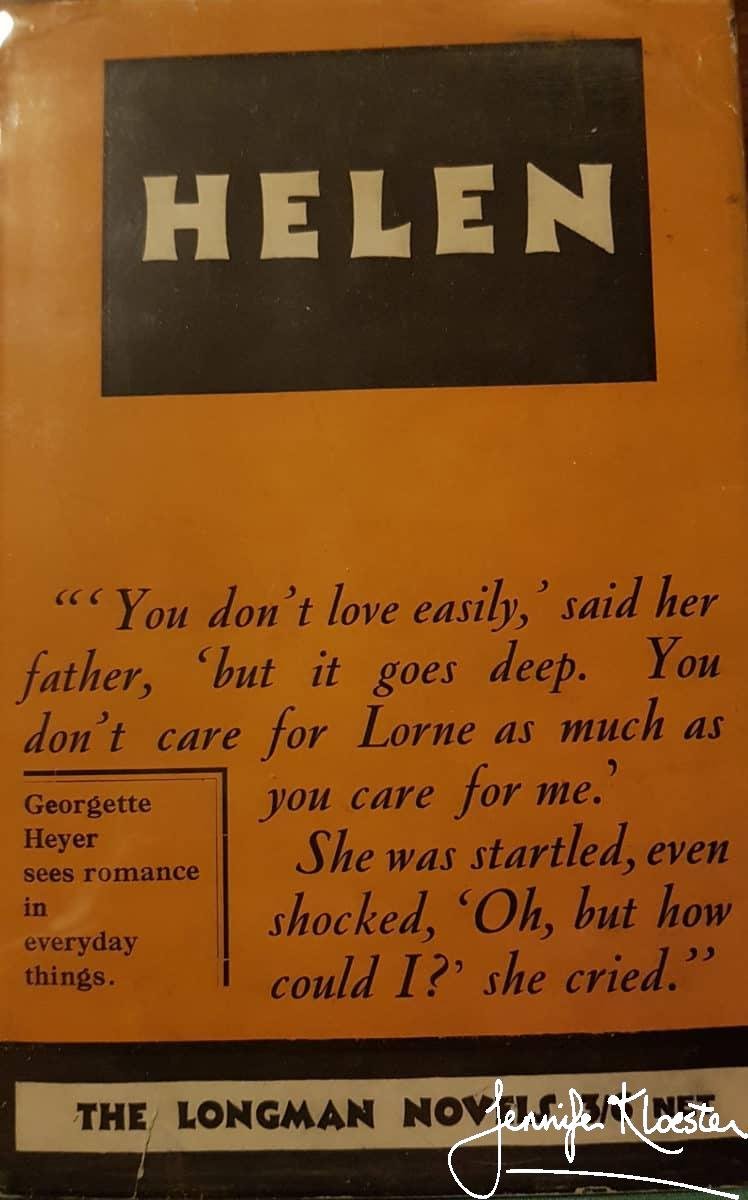

This is the first edition dustjacket.

An outlet for grief

Helen tells the story of Helen Marchant, from her birth and the immediate death of her mother, through her childhood and adolescence into the tumultuous years of young adulthood. Helen’s father decides to raise his only child himself and he and Helen become inseparable. She adores him – much as Heyer adored her own dad – and Marchant raises his Helen in his own particular way, just as Georgette’s father did:

‘Himself had taught Helen to read and write, while in long talks with her he had instilled into her a not inconsiderable knowledge of history and literature’

‘I don’t want Helen educated for a profession and made to pass Matriculation. I want her mind to expand. I want her to be accomplished in the sense that she has a wide knowledge of art and history, and literature, and the things that matter.’

Helen, Georgette Heyer, Longmans,1928, pp. 44 & 46.

There are many moments in Helen that echo moments in Georgette Heyer’s life, but the most telling part of the book comes at the end when Marchant dies suddenly and Helen is left utterly bereft. Throughout the book, Helen is depicted as someone who doesn’t show her feelings – who cannot bear ‘to have them touched’. This was Georgette’s way, too: ‘There was reserve in that voice, and an instinctive recoil from any impending intimacy.’ Writing Helen gave Georgette an outlet for her deepest feelings and it was an outlet that only she and those who knew her best would ever know about.

A grass hut in Africa

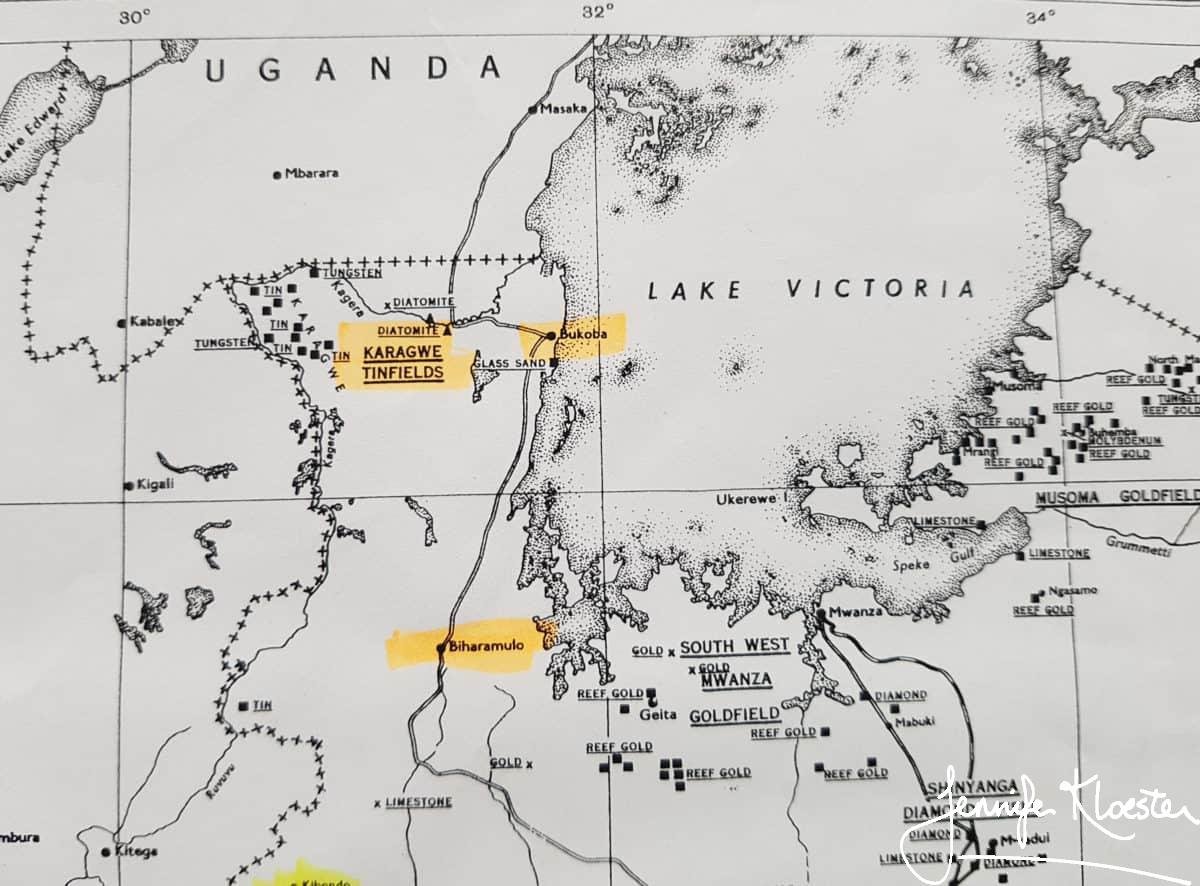

It is not known exactly when Georgette began writing Helen. She may have begun it before leaving for Africa in December 1926 or she may have written the whole novel in the grass hut that was to be her home for the next eighteen months. In the autumn of 1926 Ronald had gone out to Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania) in East Africa to prospect for tin with the hope of striking it rich and Georgette had joined there him a few months later. Their new home was genuinely remote for Ronald was prospecting in the Karagwe tin fields about eighty miles as the crow flies from the western shores of Lake Victoria. It was an extraordinary change from life in staid Wimbledon, but Georgette seems to have enjoyed the experience. In those early years of their marriage she had a definite taste for adventure and she adapted to life in Africa remarkably well.

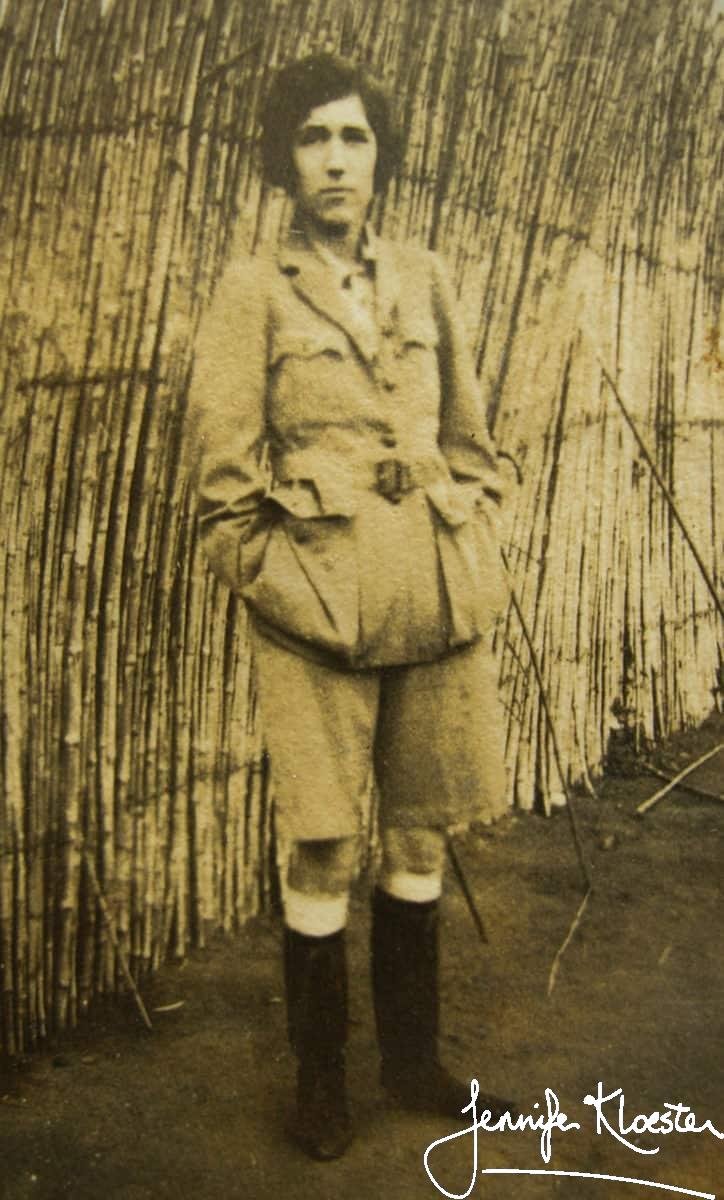

Georgette appeared to be at her most relaxed in remote East Africa. (used with permission)

Ronald hoped to ‘strike it rich’ prospecting for tin in Karagwe. (used with permission)

Georgette finished Helen in the two-room hut made of elephant grass which was her home in East Africa. She and Ronald lived in a simple compound along with a number of other British prospectors; Georgette was the only white woman for 150 miles. With characteristic humour she named their hut ‘the Manor House’ and it was there that she wrote on her lap by the light of an oil lamp. Despite the exotic location and the presence of wild animals including rhinos and antelope, apart from one article for the Sphere magazine, Georgette did not write about her African experience. Instead she was content to continue writing about contemporary life in England and eventually to pen a historical romance.

Memories of the Great War

Helen was not only an outlet for Georgette’s grief over her father’s death, it was also a way for her to write about some of her memories of the Great War. Like the fictional father in Helen, Georgette’s father had also enlisted as an over-age soldier, while Helen becomes a VAD nurse. While Georgette was too young to serve in any official capacity during the War, her mother and her two favourite aunts, Cissie and Jo, each joined the Royal Red Cross and worked as Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses (VADs) during the First World War. Aunt Cissie and Aunt Jo also became senior officers in the Royal Red Cross. Though they probably shielded the adolescent Georgette from the harsher details of their nursing experience, she was bright and observant and her understanding shows through in Helen, in which several of her characters work as VAD nurses. The novel also deals with the departure of all of Helen’s male friends for the Front and the deaths of a number of them. In a way, Helen is also a kind of tribute to the men she knew who did not return from the War.

Georgette’s Aunts Cissie & Jo (at left) in their outdoor uniforms outside the gates of Buckingham Palace after an awards ceremony. (used with permission)

Georgette’s father, Captain George Heyer, who enlisted as an over-age soldier in 1915 and served behind the lines in France. (used with permission)

A piece in Punch

During my research into Georgette Heyer’s life and writing, I was delighted to find this piece in Punch magazine. The poet is unknown, but whoever he or she was, they had undoubtedly read and enjoyed Helen. Though the poem is not without its gentle criticism of Georgette’s most autobiographical novel, it ends with kind encouragement for the young author. Georgette’s father had had several of his humorous poems published in Punch and it must have been satisfying to have her latest novel recognised in the pages of such a famous magazine. One cannot help wondering, however, what Georgette thought of this poem about Helen.

A Popular novel

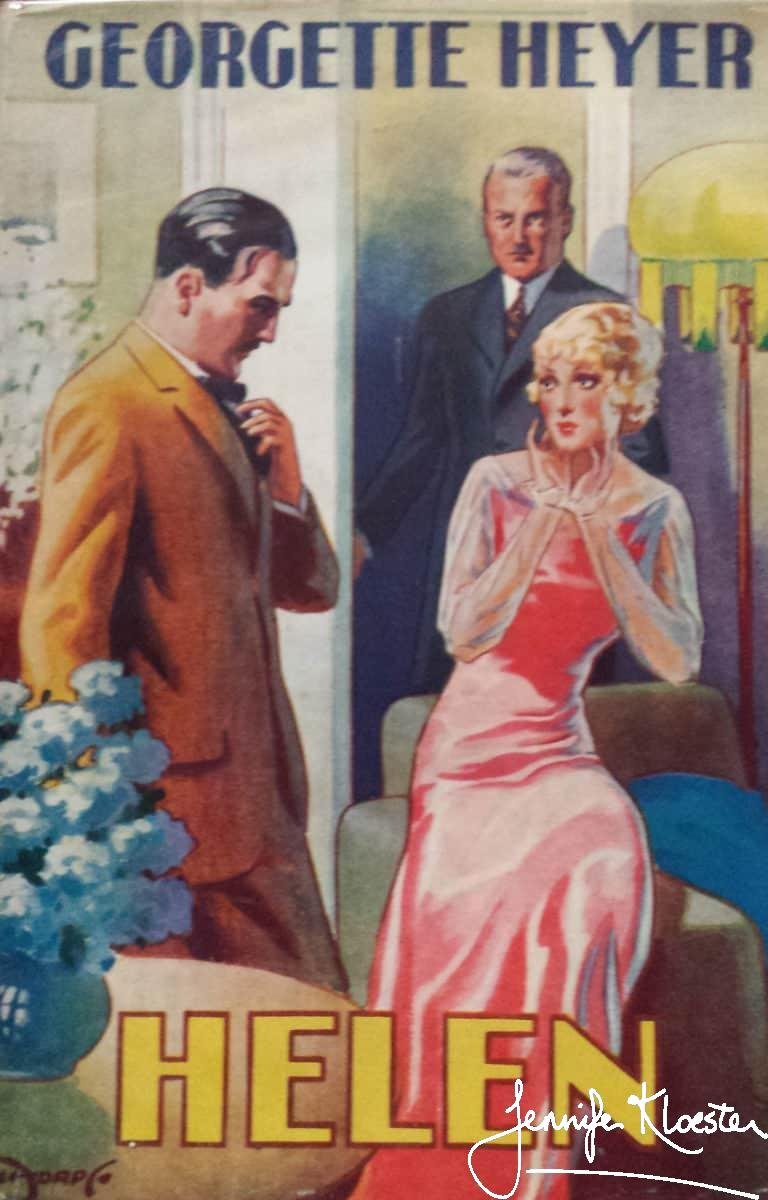

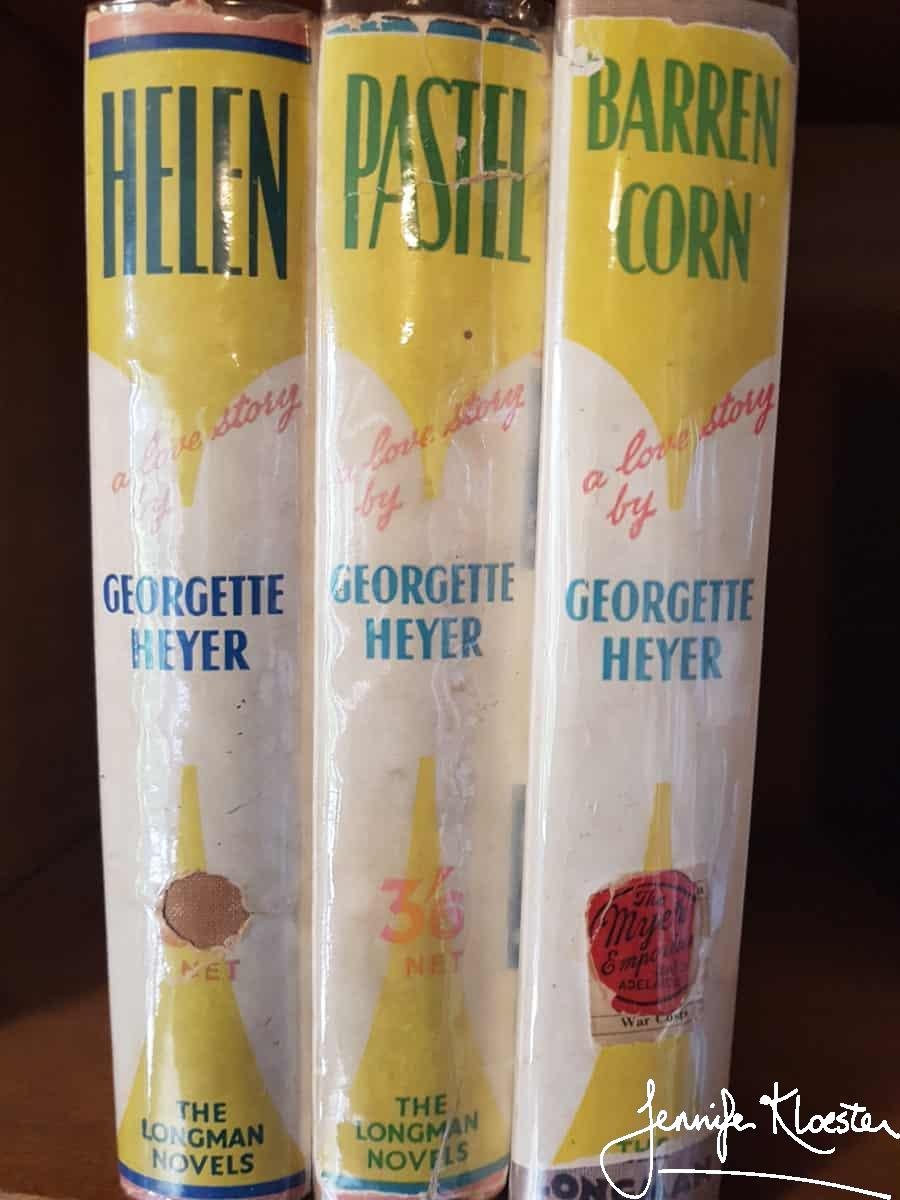

Although Heinemann would still publish Georgette’s historical fiction, her agent had found her a new publisher for her contemporary novels. Longmans were enthusiastic and pleased to publish Helen in April 1928. Helen proved popular and by October 1936, the novel had been reprinted eleven times. In their first reprint of Helen, Longmans used the original black and yellow cover art with its picture of the young woman draped around a large potted plant: An unusual image and unlikely to have pleased Georgette. The cover for the first 3/6- edition with its bold black and orange graphics may have been more satisfactory, but she would have loathed the jacket for the 1936 ‘love story’ edition. Longmans would go on to reprint each of Heyer’s four contemporary novels with similar melodramatic, coloured wrappers, with the words ‘a love story by Georgette Heyer’ on the spine. These jackets may have been the impetus for Georgette to suppress her four contemporary books in the late 1930s.

The 1931 cheap edition. Longmans used this style of jacket for each of Heyer’s four contemporary novels.

Georgette would have loathed the melodramatic cover of the 1936 edition.

Worth reading

Georgette Heyer’s four contemporary novels are well-written, interesting books, reflective of their time. Their greatest value lies in what they tell us about the author as well as the picture they draw of middle-class life in post-WWI England.. Of the four books, Helen is the most revealing about Heyer’s life and struggles with personal tragedy. She never fully recovered from her father’s death and in time her writing would become her greatest solace and the outlet for her deepest emotions.