I am now wondering what Frederica did & why, & whatever induced me to embrace writing as a profession. I haven’t a clue to any of these problems.

Georgette Heyer to Pat Wallace 30 January 1964

“An auspicious date, too”

On 12 February 1964, Georgette Heyer signed the contract for her new novel, Frederica. It was to be her second book for the Bodley Head, and, as Georgette explained to her new publisher, Max Reinhardt, it was ‘an auspicious date, too: my most successful achievement has this day attained his thirty-second birthday!’ Her son Richard was now a successful lawyer and an up-and-coming bridge player who had already caught the eye of several of England’s most notable players. Life was good for Georgette and her family and she had begun Frederica in her usual style with an idea of the plot and a cast of memorable characters. However, the book would not be written at her usual speed and by May she had only “perpetrated some 48,000 words”. While, for many authors this might be considered a considerable achievement after just three months of writing, for Georgette Heyer it was very slow going. Looking back across her writing life and calculating from her many letters just how long it took her to write most of her novels it is easy to gain the impression that, almost without exception, her books seemed to write themselves. Of course, this was not true. As Heyer herself said, she wrote her novels “with blood, sweat and tears” – she just did it at superhuman speed! In 1964, Frederica would prove to be an exception to this long tradition. The truth was that Georgette was unwell. Things finally came to a head in late June 1964. After her regular correspondence with Max over the previous few months, her publisher must have been surprised to receive a letter from Georgette’s husband Ronald:

Dear Max,

Your letter of the 30th June arrived rather opportunely & Georgette has asked me to let you know the situation. Last Monday [29 June 1964] she was struck down by some sort of internal disorder & after some trying days (and nights!) we managed to get her into the private wing of Guy’s Hospital… The present attack is subsiding but is not quite over yet. When it has they intend to give her a full examination to see what the trouble really is. I think this has been pending for some time & is probably responsible for the slow progress she has been making on the book. Anyway, it will be a great relief to get a certain diagnosis after which I hope she will be quite all right. It means, though, that she cannot possibly finish the book this month & so your alternative plan will have to be adopted.

Ronald Rougier to Max Reinhardt, 5 July 1964

“a bloody great gash!”

The alternative plan was to allow Heyer to finish the book by autumn in time for Christmas release. However, this plan, too, was disrupted for Georgette’s “internal trouble” proved to be a large kidney stone and she was immediately scheduled for surgery. Unlike today, in 1964 the surgical removal of a kidney stone meant a major operation and almost a month in hospital. Georgette would not return home until the end of July and when she did it was with the expectation of a long convalescence. As she explained to her publisher, the surgery

was far from funny, & has left me with what the hospital staff describes as A Beautifully Neat Incision, & Ronald as A Bloody Great Gash. Ronald is right. It is some fifteen inches long, & has severed all the “Torsion” muscles. Hence the pain I am still suffering.

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 2 August 1964

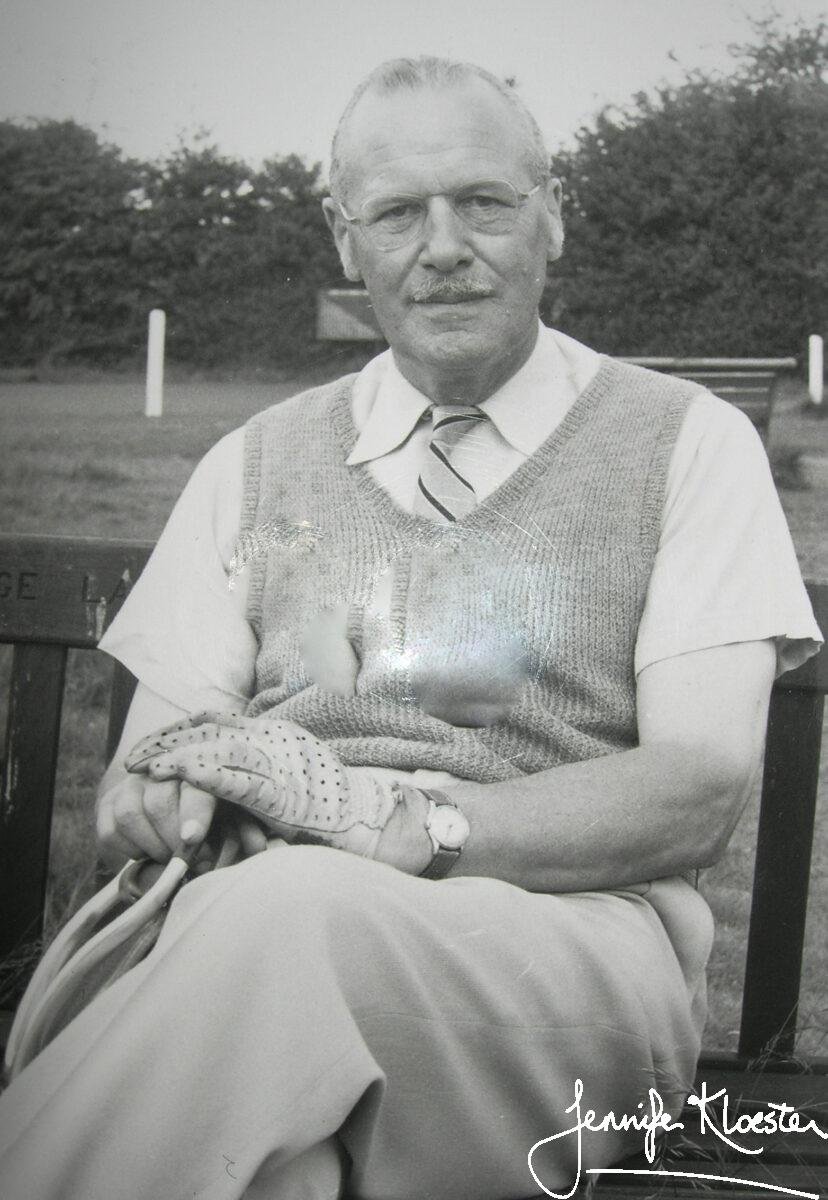

Georgette would take time to recover and it is not surprising that it was some months before she picked up Frederica and began writing again. Her surgeon had told her that she would be an invalid for at least six weeks but that it would be Christmas before she was “on top of [her] form again”. In late August she and Ronald went to Greywalls in Gullane, Scotland, for a much-needed holiday. Georgette always felt better in what she found to be the “bracing air” of Gullane and the calm privacy of Greywalls. Originally designed by the famous architect Sir Edwin Lutyens and with a garden by Gertrude Jekyll, Greywalls was built in 1901 as a “gentleman’s residence”. It is a superb house and was the ideal spot for someone of Georgette’s temperament to recuperate. With excellent food, comfortable rooms and no one to bother her or ask her questions about her writing it had long been her favourite holiday destination. She loved Greywalls’ peaceful atmosphere and would sit by the fire reading or knitting or just enjoy the glorious views across Muirfield Golf Course to the Firth of Forth. In late August she and Ronald left London for Scotland but, although she took Frederica with her, Georgette did little or no work on the manuscript.

“absolutely first-rate”

The Rougiers returned home in September and by October Georgette was able to tell her publisher that Frederica was “progressing steadily”. She was still not completely well but was slowly recovering. She eventually finished Frederica in March 1965 and told Max that, at 145,000 words, it was too long and probably needed cutting. While she knew that her readers loved her longer books, she was also aware that she had never before experienced a six-month interruption to one of her novels. She was concerned that the manuscript might be full of “irrelevant meandering” and repetition. Her publisher was quick to reassure her. Reinhardt read Frederica over a weekend, thought it “absolutely first-rate” and encouraged her to leave it long. Georgette read the manuscript twice and both Ronald (always her first and best proof-reader) and a Bodley Head reader pored over it until the manuscript was awash with corrections in green, blue and red ink. In spite of her grumbles, Georgette was not really disheartened by Frederica. On reading it she was actually “a little cheered: it didn’t seem to be quite so long or as dull as I’d thought”. After more than forty years of writing her habit of self-deprecation was well established to the point of being almost an intrinsic part of her writing ritual.

A foundry in Soho

Frederica marked the first time in her life that Georgette Heyer did not fulfill her contract and deliver a manuscript as promised. She felt dreadful about what she perceived as a personal failure and it did not matter that it was not her fault. In December she wrote a heartfelt letter to Reinhardt to say: “I wish I weren’t failing you like this: I seethe and seethe, for Never before have I fallen down on a contract. Try to forgive me! You can’t feel more disappointed & furious than I do. Yes, & Miss Lindsay, of Harrods’ Book Dept., tells me that she is assailed by hundreds of customers, demanding to know Why no new Heyer, & When a new Heyer?”

Of course, it did not really matter that the new novel was delayed, as her publisher well knew. By now, Georgette Heyer was a major bestseller and a household name. Whenever Frederica was published it was certain to sell well. The long gap in her writing did have one unexpected consequence, however, for Frederica contains one of Heyer’s rare factual errors. In the winter of 1965, a few months before the book came out, the novel was serialised in Woman’s Journal and a fan wrote to point out the mistake. In chapter eight of Frederica, Georgette’s “long-suffering hero”, the Marquis of Alverstoke, finds himself increasingly embroiled in the Merriville family’s affairs and surprises himself by taking Felix to see a foundry. In her usual way, Georgette had been to the London Library to “mug up” on balloons and all things industrial, including steam power and foundries. As she had explained to her publisher the year before:

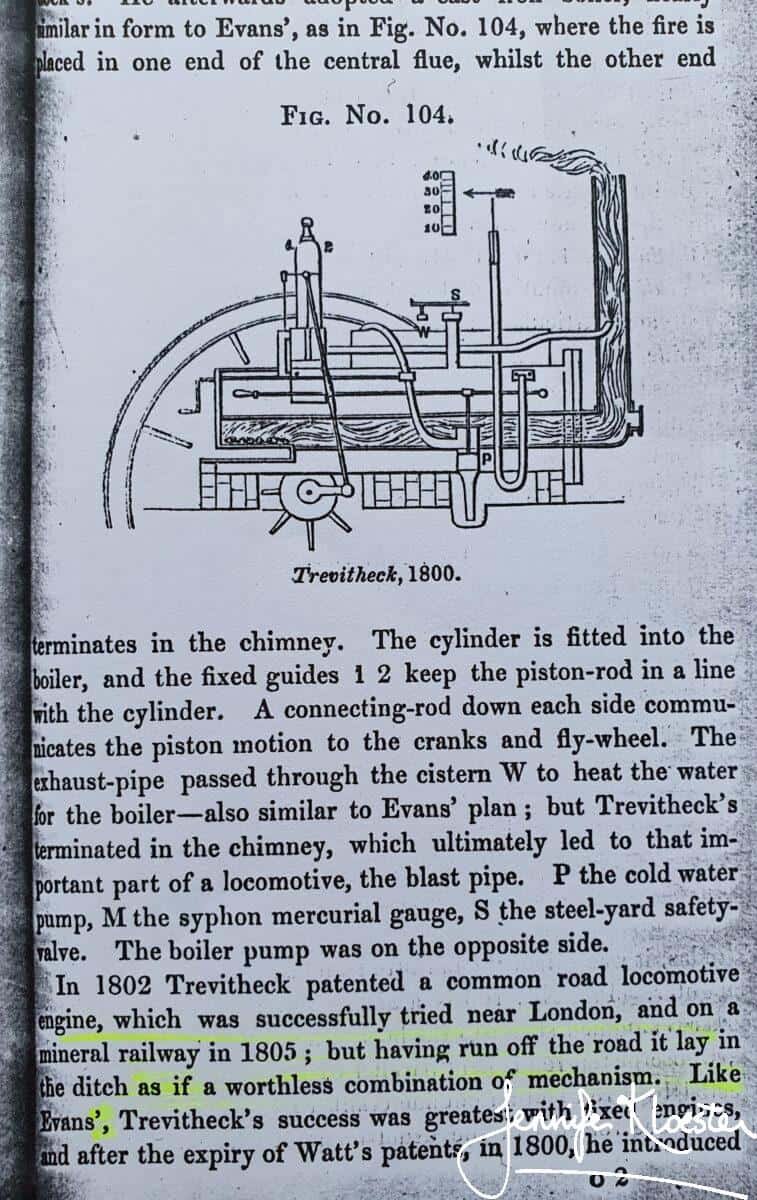

The youngest member of Frederica’s family is mad about steam-locomotion, & coal-gas. Why I do these things I can’t imagine, for as I don’t know anything about such matters it means Work; & I am forever consulting various volumes, borrowed from the London Library.

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 31 March 1964

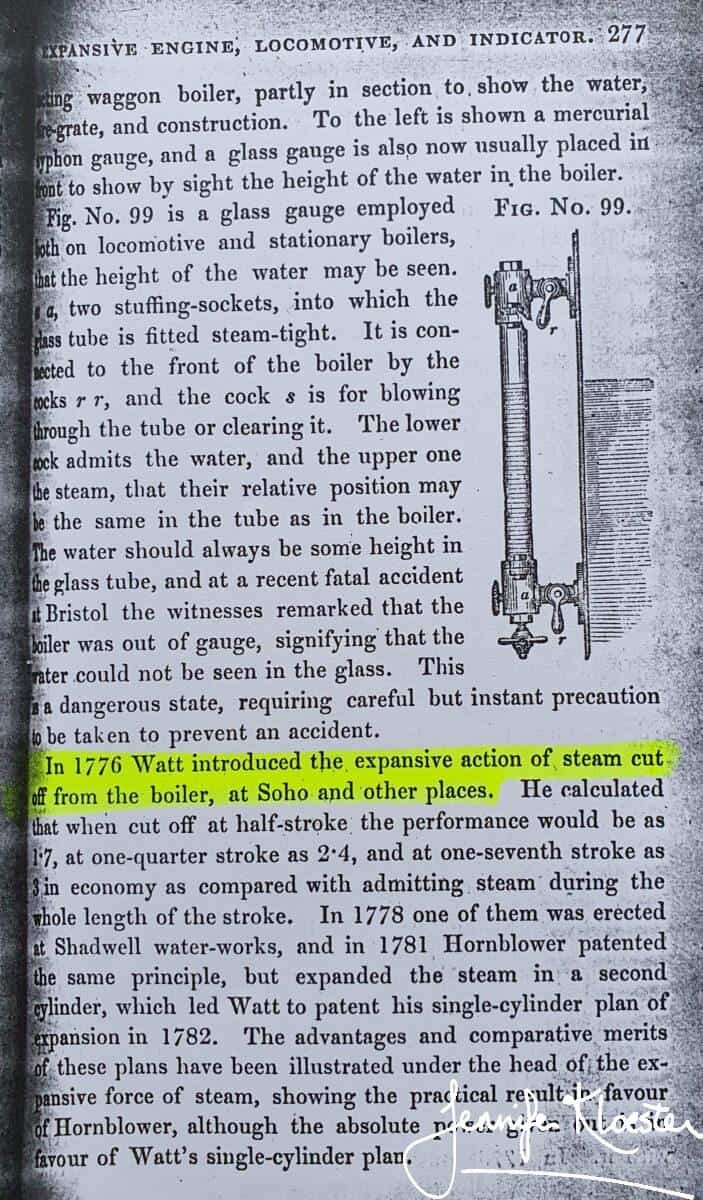

One of the books she consulted was John Sewell’s, Elementary Treatise on Steam and Locomotion (1852). In which she had found a sentence about a steam boiler which read: “In 1776 Watt introduced the expansive action of steam cut off from the boiler, at Soho and other places.” On the next page there is a reference to Watt’s ‘first double-acting engine erected at Albion-mills, London”; there is no mention of Birmingham. Georgette had thus assumed that the Soho mentioned in the book was Soho in London. At the time she had thought Soho London “an odd place for a foundry” and “had meant to look it up”. Unfortunately, kidney stones and major surgery followed by a long convalescence had pushed the question from her mind. The error remained and, although Georgette thought she might be inundated with letters pointing out her mistake, she only ever received one letter about it. The error remains to this day.

England’s No. 1 Bestseller

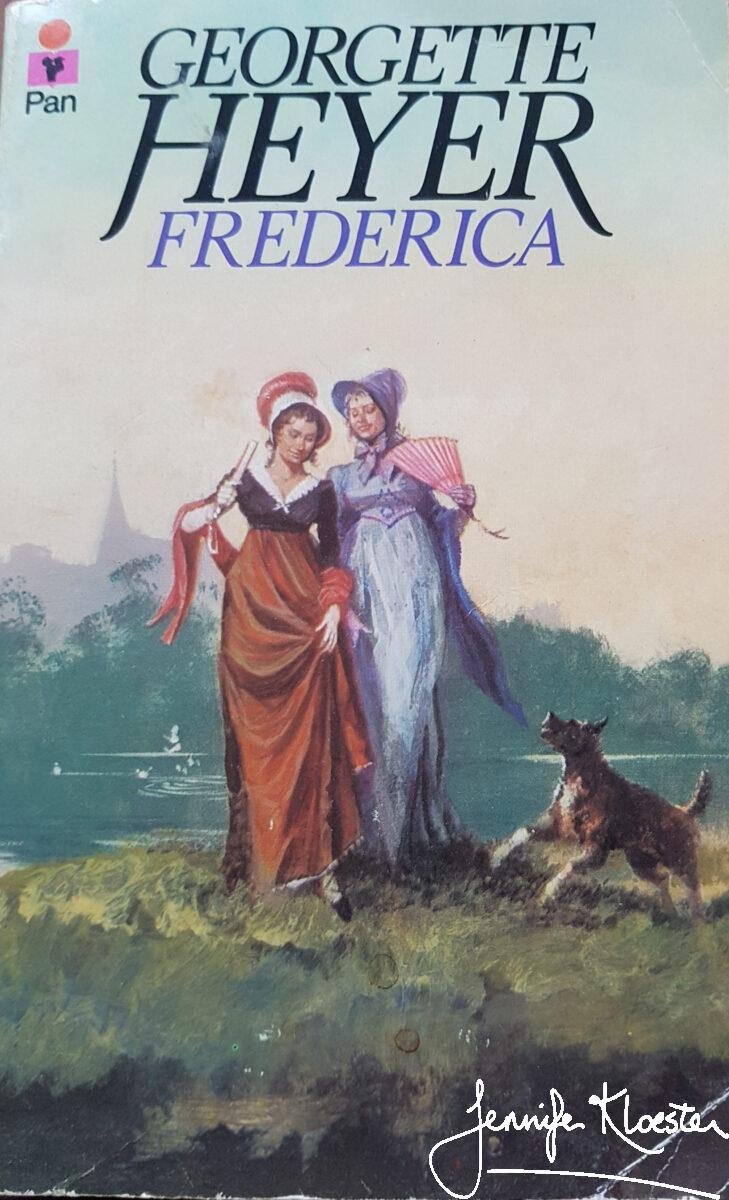

Frederica was a huge success. It came out in September 1965 with a subscription in excess of 50,000 copies and shot straight to the top of the bestseller list. A few weeks later Max returned from a business trip to Scotland and wrote gleefully to his star author to say: “I was feted by all the booksellers entirely thanks to the success they were having with Frederica.” In typical Heyer-fashion Georgette ended her reply to him with a characteristic comment: “I envy you your Scotch trip, but really, Max, I wasn’t born yesterday! Feted because of Frederica indeed! Now I’ll tell one!” Reinhardt was right, of course. Georgette had become a huge success and her novels were selling thousands of copies a week. She was also a hit in America where Georgette’s US publisher, Dutton, were keen to promote her. Drawing on her UK success they placed a large advertisement extolling Frederica‘s virtues in The New York Times. While the two major paperback publishers, Penguin and Pan, offered Georgette £3000 and £4500 respectively for the right to publish Frederica two or thee years after its release.

A very special Christmas edition

Dear Georgette

We shall have sold 60,000 copies of Frederica by Christmas, when the third reprint will be available. Our sales of Frederica are already higher than thos of False Colours. We are all delighted and so, I hope, are you. Frederica has been the great best-seller this Christmas and maintained its lead as a best-seller in the trade papers. Smiths alone have now bought 8,000.

Max Reinhardt to Georgette Heyer, letter, 7 December 1965

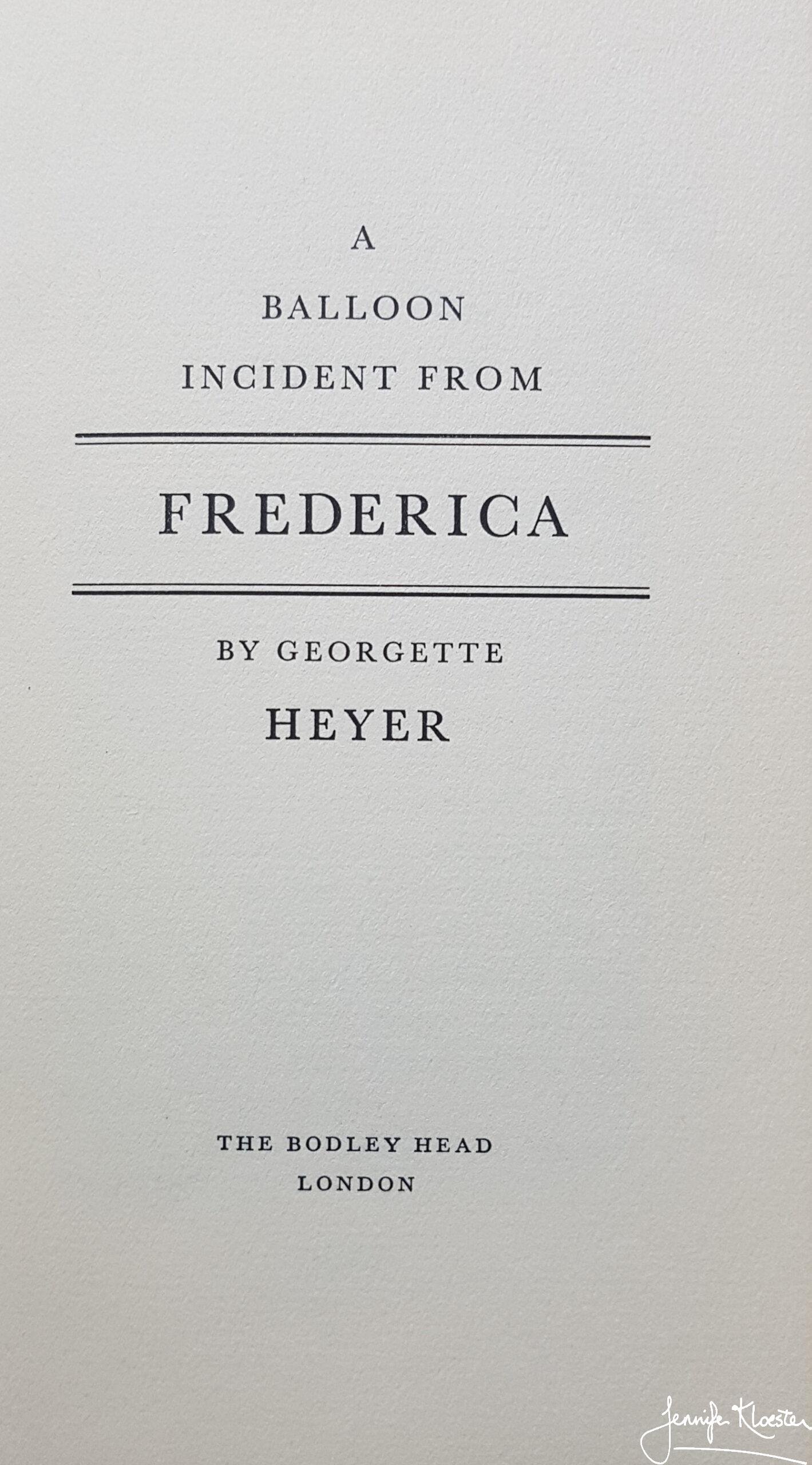

Given Frederica’s enormous success, it is not surprising that the Bodley Head chose to use an excerpt from the novel for their special Christmas booklet. Beginning in 1961, the Bodley Head produced one of these delightful booklets each Christmas in an edition of 200 copies for private distribution. The practice continued for over twenty years until 1984 with the publisher choosing a passage from one of the most prestigious of that year’s publication list. Georgette must have been delighted (even if she didn’t show it) to have been chosen for the 1965 edition. “A Balloon Incident from Frederica begins with the words: “And, indeed, the silken bag, which had previously been spread on the ground, could now be seen, rising above the heads of the crowd” and ends with Jessamy – greatly relieved to have the Marquis taking charge of the rescue mission – exclaim: “You’ll go with me yourself? Oh, thank you! Now we hall do!”