‘Though like Ronald, you don’t know Anything about Anything, I feel your instinct may inform you that this is just the sort of nonsense which suits my particular brand of humour’

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 1963

Heyer moves to Bodley Head

In 1963, Georgette Heyer left Heinemann, her publisher for nearly forty years, and moved to the Bodley Head. It was a move that she had come to see as inevitable after her close friend and publisher, A. S. Frere, had been pushed out of any active role at the firm. In 1961 the company had approached bankruptcy and Frere was one of several people who wanted to sell Heinemann to the American publisher, McGraw-Hill. The deal fell through, however, (it was strongly felt by some in the company that Heinemann should remain an English publisher) and Frere lost his position as chairman. He was appointed president instead and “kicked upstairs” into what amounted to little more than a token role. He was no longer in charge and his direct relationships with authors he had nurtured and befriended over many years were effectively severed. In late 1962, fed up with no longer having an active role at Heinemann, Frere resigned as president and moved to the Bodley Head which was owned and managed by his friend, Max Reinhardt. With Frere went Georgette Heyer, Graham Greene, Eric Ambler and George Millar. Their departure was a serious loss to Heinemann and both Georgette Heyer and Graham Greene expressed sadness at the way things had unfolded:

“Very many thanks for your letter – & for my enjoyable lunch! The occasion was a gloomy one, but I am so glad to have met you; & I hope that my secession from the ranks won’t preclude our meeting again. You were very persuasive, but my decision wasn’t reached without a great deal of thought. In fact, to be asked to think any more about if almost makes me drum with my heels: Frere has been preaching Thought, Consideration, & Caution ever since I told him that I should leave the firm when he did. I don’t doubt I should get on beautifully with you, but there is more to all this than the personal friendship angle. A lot of very murky water has been flowing under the Heinemann bridge, & I don’t like it. It can serve no useful purpose to enlarge upon what I said to you yesterday, so I will merely say that I am sorry, but my mind is made up.”

Georgette Heyer to Derek Priestley, letter, 9 January 1963.

“…after thirty-two years with Heinemann, it has taken me many months to make up my mind, but a publishing firm to an author means a personal contact, a personal sense of confidence reciprocated, and this I can no longer find in a company of whom the directors are nearly all unknown to me.”

Graham Greene to A.S. Frere, letter 16 October 1962.

Graham Greene left Heinemann in 1962 photo Fortepan Wikimedia Commons

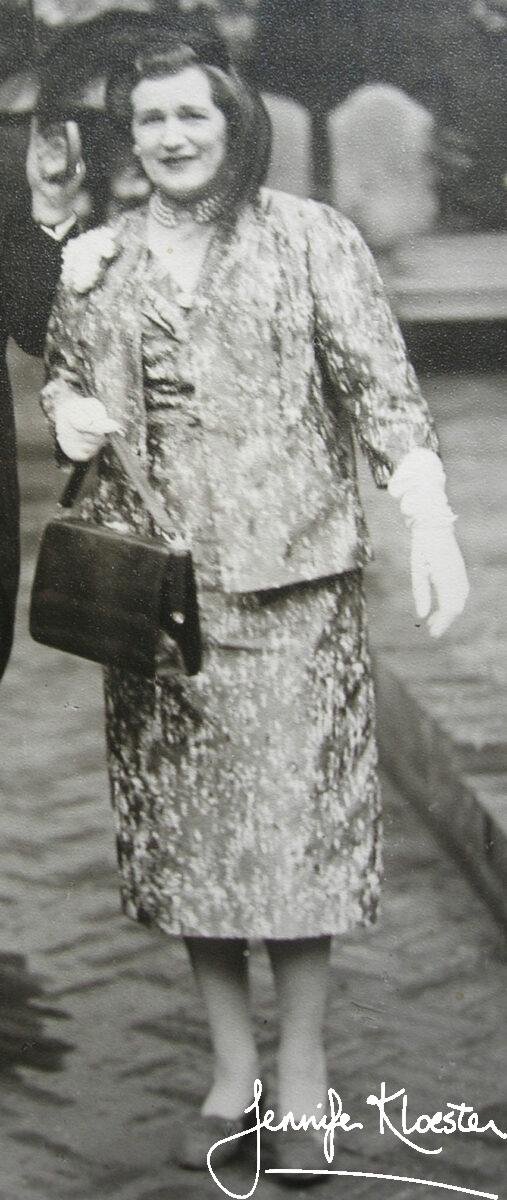

Georgette Heyer left Heinemann for Bodley Head in 1962.

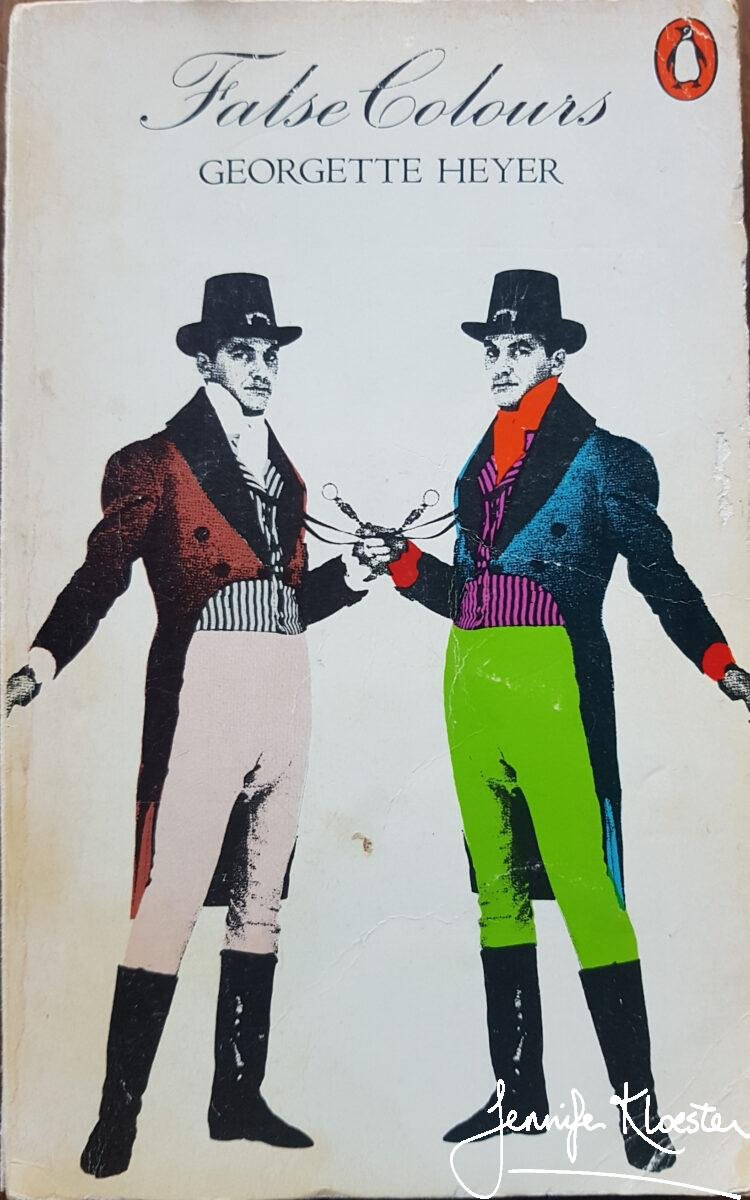

A new novel for her new publisher

Two days after writing to Derek Priestley to assure him she would not resile from her decision to leave Heinemann, Georgette wrote her first letter to her new publisher. Max Reinhardt was the part owner and Managing Director of the Bodley Head. A tall, solidly-built man and very charming, he was also a talented bridge-player, a member of the Savile and Garrick Clubs, had lived at Albany and was a good friend of Frere’s – all things guaranteed to win Georgette’s approval! In time she and Ronald would become good friends with Max and his American wife Joan. Although her first two letters to her new publisher began with the formal “Dear Mr Reinhardt” Georgette soon abandoned the practice and by April her third letter told him frankly: “on second thoughts I’ll alter that to Dear Max, because now we have entered into what I hope will prove an enduring association the sooner we abandon formality the better it will be for both of us.” A congenial publisher (and likely advised by Frere), from the beginning Reinhardt knew just how to respond to Georgette. In February 1963, shewrote to him with news of her new novel: “at the moment I can only give you the title, which is False Colours, & my assurance that I do know what it’s going to be about!”

Georgette was intensely loyal to her adored friend, A.S. Frere and followed him to Bodley Head..

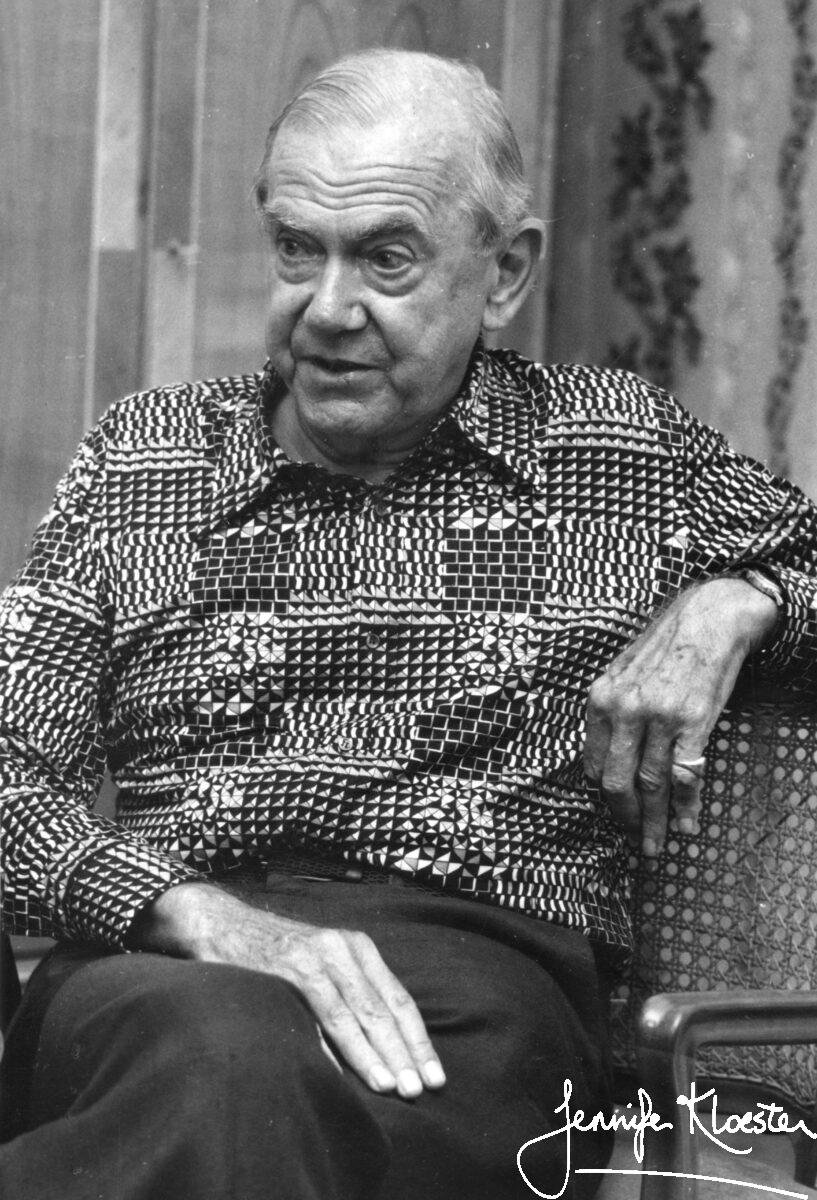

In 1963 Max Reinhardt became Georgette’s publisher. They would remain good friends until her death in 1974.

A detailed synopsis

Georgette knew exactly what the story was to be about and on 15 April wrote out a detailed synopsis of the planned novel. She had originally intended to send the blurb to Reinhardt, but – perhaps feeling a little unsure of her new publisher – changed her mind and instead sent it to Frere with a humorous explanation:

I have had a shot at writing a précis of the book for M.R.’s perusal, but I thought the result would very likely cause him to suffer a stroke, so I didn’t send it to him. Instead, I will favour you with an account of What this Book is About. An Easter Treat, ducky! Perhaps, in addition, you would like me to come & read my first chapter aloud to you?

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter 15 April 1963.

At almost 1700 words the précis is a remarkably detailed account of the book that would become False Colours. Georgette had an extraordinary ability to see her story and characters in full before she even put pen to paper (or, by now, fingers to typewriter!). While she might have doubted her new publisher’s reaction to her plan for the novel, Frere had no such qualms. He immediately sent her synopsis to Max, exactly as Georgette has written it. A week later her new publisher sent her a proposed blurb for the book cover based on her outline. Heyer was impressed and, assuming that he had written it himself, told Max that he had made her book “sound positively scintillating”. It is perhaps unlikely that Reinhardt wrote the blurb himself although he does seem to have actually read False Colours. In later years his former secretary, Belinda McGill, reported that Max “was not a great reader and that it was Joan who probably read the novels and told her husband about them”. By mid April Georgette had written 40,000 words and despite “a sticky start” told Max that:

“I seem to be getting on fairly well with False Colours – should be getting on much faster if I would overcome a bad bout of insomnia. I did sleep for 4 hours last night, so perhaps this scourge is on the wane. A week ago it was so bad that I came very close to breaking what has so far been an inflexible rule: No Drugs.”

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 15 April 1963.

No Drugs

Now in her early sixties, Georgette could no longer maintain her old regimen of staying up all night to write. Twice in the 1950s a doctor had prescribed Dexedrine for her influenza and she had discovered to her surprise that the medication had a useful side effect. If she took a tablet in the evening she could once again stay up and write all night. Heyer had no knowledge of what we would today call “uppers” and (despite some reviewers’ incorrect assertions) she did not rely on drugs to write her novels. Only two of her fifty-six books fell into those two short-lived dexedrine weeks. In what was to be the final decade of Heyer’s life her work would be interrupted by various episodes of ill-health, but her love of writing and telling wonderful stories always prevailed.

Remarkably, despite having written 49 novels in 40 years, False Colours and the two books that would come after it would each have new plots. This time the story was to be about identical twins – Evelyn and Kit Fancot – whose delightful but utterly impecunious mama is the cause of their problems. Heyer based Lady Denville on the historical Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (1757-1806). While her husband is alive, Lady Denville (like her historical counterpart’s) must try to keep her extravagant lifestyle and enormous gambling debts from her husband. After Lord Denville dies, it falls to her sons to try and save her from financial disaster. In creating Lady Denville, Heyer had in part been inspired by a request from actress Anna Neagle who had asked Georgette if she would “write a nice middle aged part for her”. Neagle’s husband, the producer, Herbert Wilcox, hoped to turn False Colours into a television series with Anna in the starring role. Though she would have been perfect as the entrancing Lady Denville, the projected series didn’t happen. The book, however, was a huge success, with a second printing ordered even before it was published. Released in October 1963, within two months False Colours had sold 50,000 copies and Georgette had another hit on her hands. (Next week’s blog will include parts of Heyer’s synopsis for False Colours)