As you will see by my use of the typewriter, I am busily engaged on my new book. There is no room to write at my desk once I’ve set up the Infernal Machine! I am now midway through the third chapter, and am – contrary to my expectations – Quite Enjoying Myself! I don’t think it’s too bad – in fact, I think that what I’ve done is Quite Good! Anyway, it is – to judge by Ronald’s chuckles! – quite amusing!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 8 November 1969

A huge bestseller

By 1969, Georgette Heyer was a household name. Her birthday was listed in the Times and her previous two novels: Black Sheep and Cousin Kate had each sold more than 60,000 copies in hardback in the first two months of publication. With her ever-increasing success also came an increasing number of letters from fans, along with an increasing number of requests for interviews, invitations to special events and requests for her to speak at various literary functions. In February 1969 she turned down an invitation from PEN to be Guest of Honour at a sherry-party in Edinburgh, holding to her lifelong rule that “I never make Public Appearances”. It was a rule that sometimes caused her a pang of regret – especially later in her life. However, she had no wish to attend a sherry-party with herself as the focus of attention. Despite her immense success as a writer, Georgette Heyer had no desire to be in the spotlight, preferring instead to live privately and securely behind the mask of “Mrs Ronald Rougier”. As her son Richard explained, she was not only intensely shy but she could also see no reason for anyone to be interested in her but only in her books. It was because of this that she asked her publisher’s secretary, the kind and efficient Belinda McGill, to reply to the Scottish arm of PEN on her behalf:

If you can refuse for me, without giving Grave Offence, I shall be Everlastingly Grateful to you! You could say (with almost complete truth) that I never make Public appearances; you could say (with COMPLETE truth) that since I refused, many years ago, to attend an English PEN club luncheon, I feel it would be most invidious of me to go to a sherry-party thrown by the Scottish Centre of the International PEN; you could say that I regard my Scottish holidays as Complete Escapes from my Literary Life; you could say that Miss Heyer has no desire to figure as a Guest of Honour at this or any other party

Georgette Heyer to Belinda McGill, letter, 6 February 1969

Though practically inconceivable in today’s publishing world, Georgette’s refusal to engage in personal publicity did not harm her sales. The money was rolling in and, with the Booker deal behind her, for the first time since her father’s death in 1925, she had allowed herself to completely relax – to the point of taking an entire year off from writing. She had written nothing since finishing Cousin Kate in April 1968 and months later told her publisher “I am enjoying my idle year”. 1969 would prove to be one of Georgette’s rare years without a book. It had been the Booker Brothers deal that had finally relieved her mind of financial worry. For the first time in her long career the absence of the “annual Heyer” was not due to a loved one’s death, her own poor health, or to War. This time she took a year off simply because she wanted to. Perhaps we should be grateful that Georgette Heyer worried over money as much as she did, because without that pressure (real or perceived) she may never have written so many enduring bestsellers!

Holidays and a new book…

IHer “idle year” was to end in August when she and Ronald were to go to Scotland as usual. This time they were to stay at the famous Gleneagles Hotel (which they did not like) and the Marine Hotel (which they did) while Greywalls underwent renovations. However, before that holiday took place, they were to go to Iceland. It was Ronald’s wish to see that beautiful country and he had convinced Georgette to accompany him. On the 8th July 1969 they left for Iceland for a fortnight’s holiday. She had enjoyed their last Scandinavian holiday and she found Iceland to be “a fantastic country – like nothing I’ve ever seen or dreamt of”. She loved the magnificent scenery and the bracing Icelandic air and told friends “I shall always be glad I’ve seen it'”. The Iceland trip proved to be exactly what she needed after suffering from another “ghastly throat” in the spring. The truth was that Georgette’s health had been indifferent for some time. She had been beset by various ailments, all of which had taken their toll on her both physically and mentally. Iceland did her good, however, and on her return she made a conscious decision to begin writing a new book once they had returned from Scotland.

“The thing to do is to start writing the book”

Back in London in September, it would be a little while before Georgette turned her attention to the new novel. But in late October she took her publisher to lunch and gave him the glad tidings. Max was delighted, promised to keep the title secret, and instantly began planning an autumn publication: “If you can let us have the book by the end of March or the end of April, it would give us all the time we need to do a good job of selling it and getting you the highest subscription you have ever had.” A week later Georgette had started writing and was able to cheerfully report that:

I am now midway through the third chapter, and am – contrary to my expectations –Quite Enjoying Myself! I don’t think it’s too bad – in fact, I think that what I’ve done is Quite Good! Anyway, it is – to judge by Ronald’s chuckles! – quite amusing!

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 6 November 1969

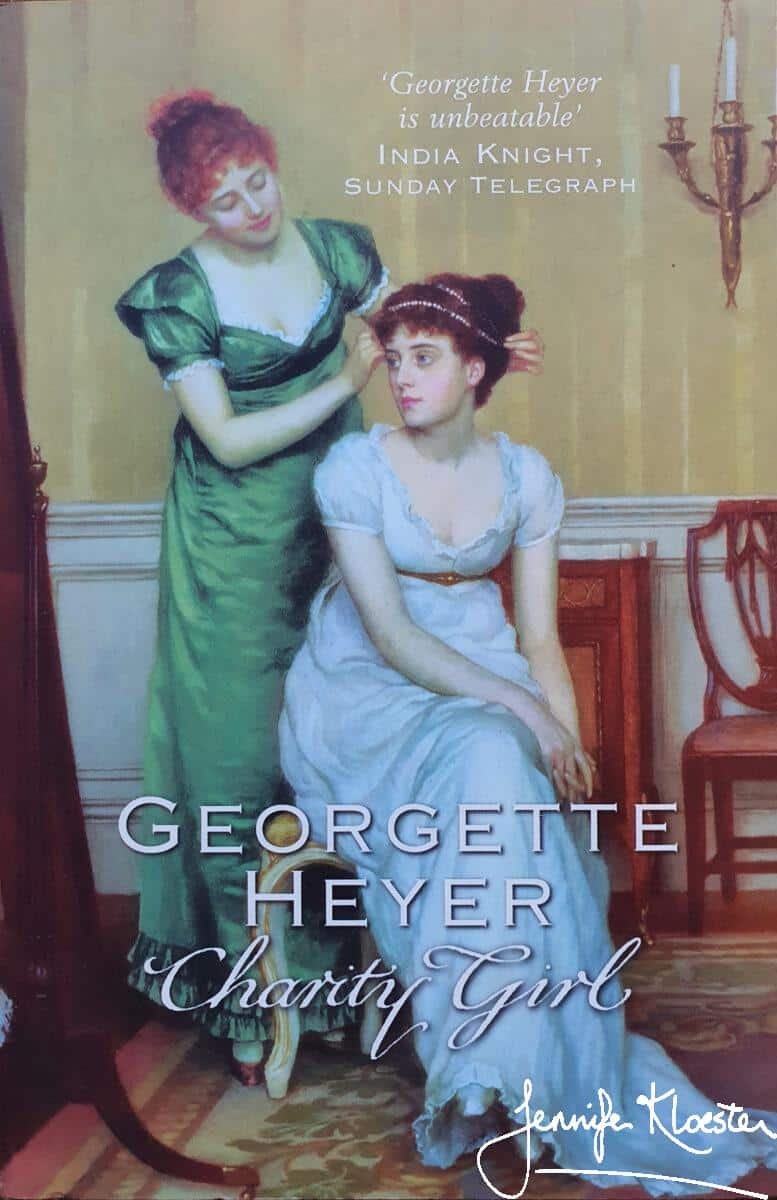

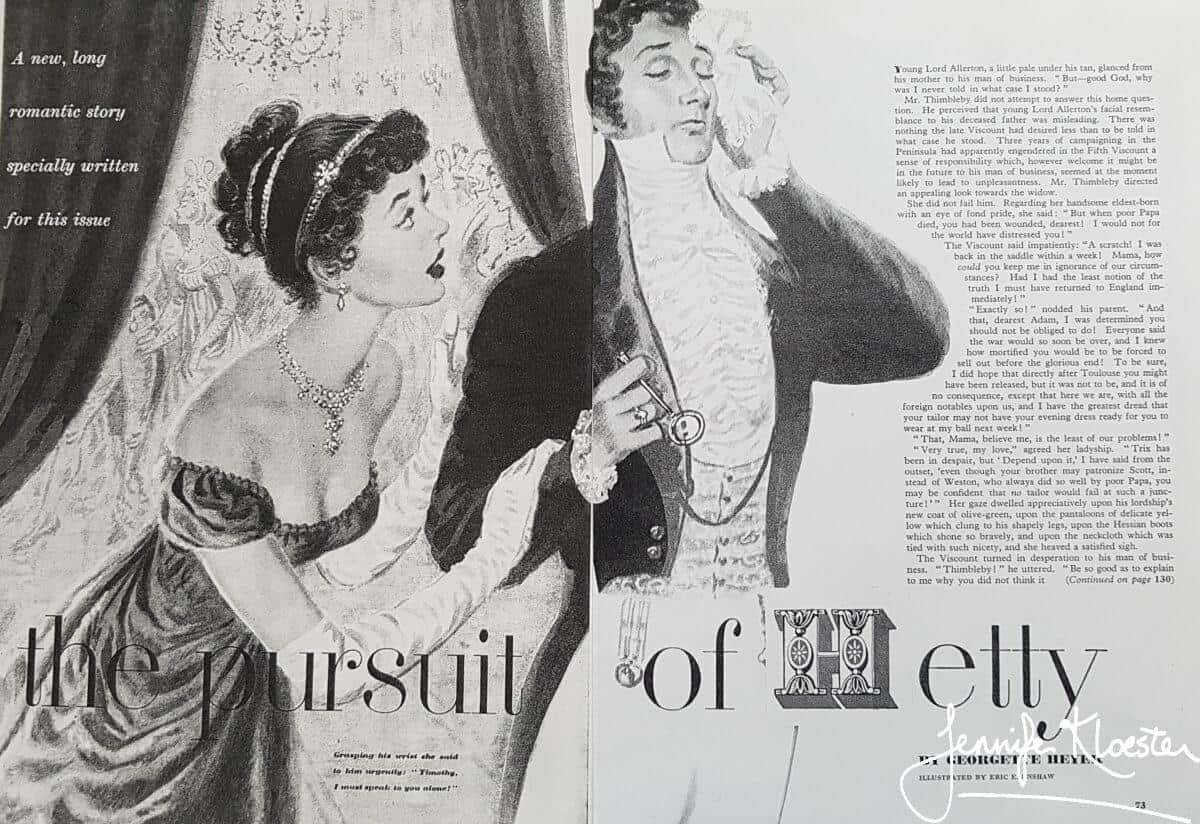

The new novel was to be very different from her last. Despite Cousin Kate‘s immense popularity – within a year it had earned Georgette almost £22,000 ($320,000 in today’s money) – she had taken a set against the book. She even told Max Reinhardt that it “must surely take a prominent position amongst the worst books I’ve ever written.” While some may agree with her, many do not. But there is no doubt that her new novel – to be called Charity Girl – would be quite different from Cousin Kate. A much more light-hearted tale than the previous book it would focus mainly on the hero – the kind and charming Ashley Carrington, Viscount Desford. His whose attempt to rescue sweet Charity “Cherry” Steane from her wretched life of dependence and charity would lead him a merry dance. The seed of the novel may be found in Georgette’s 1953 short story “The Pursuit of Hetty” (later renamed “To Have the Honour”), which Georgette had been commissioned to write for the special Coronation edition of Good Housekeeping magazine. Though there are decided differences between the two stories, it is the presence of “Hetty” in the first and “Hetta” in the second, the hero’s long resistance to marrying his “best friend” because he is blind to his true feelings, and the part played by his sibling in bringing them together, that are common to both stories. Heyer also plays with the theme of charity in the novel. Charity is not only the name of the young woman whom Ashley rescues, it is also the driving force that prompts him to spend much of the novel trying to solve her precarious situation. Ashley is one of Heyer’s kindest heroes and it is his charitable heart that compels him to persist in his quest when others urge him to abandon Charity (Cherry) to her fate.

A “more lighthearted book”

Despite continuing problems with her health, Georgette enjoyed writing Charity Girl and creating laugh-out-loud scenes for her readers to enjoy. Unlike some of her other books (The Convenient Marriage and Sylvester among others) she had not worked out the entire plot in advance of writing. As she explained to Reinhardt:

Certain developments are still undecided, but I have always found that when I can’t make up my mind whether or not to make this or that happen the only thing to do is to start writing the book, and allow the later events in it to grow on their own. Of course, this does sometimes lead to a ghastly period in the middle, when one can’t think what to do next; but it frequently leads to no problem at all, one’s characters deciding the matter without any assistance from their author. At all events, I hope (and even dare to believe!) that this will be a better, and certainly more lighthearted a book than Cousin Kate.

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 6 November 1969.

Unfortunately, and despite her “idle year”, ill-health disrupted Georgette’s writing yet again. Used to writing her novels quickly – usually in six to eight weeks, it was frustrating to find herself laid up and unable to work on the new novel. Charity Girl was progressing, however, and the interruptions do not seem to have affected Georgette’s ability to finish her book before her own self-imposed deadline. A few days after Christmas, however, she wrote to her publisher to express her regret that:

“I’ve done no work since this scourge knocked me for six, so that I’m not as far advanced as I’d expected to be. However, I’ve done between 30 & 35,000 words, so provided I don’t take too long to recover my form I don’t think this ought to matter much. At the moment my head swims when I try to get down to the job, but I am going to get my doctor to give me a strong tonic.”

Georgette Heyer to Max Reinhardt, letter, 30 December 1969

Her publisher, knowing the worth and work ethic of his most successful author, instantly wrote back to reassure her:

My dear Georgette,

We were so sorry to hear from the letter that you sent to Joan that you haven’t been too well over the last fortnight. I am relieved that you are better. I don’t know how you managed to write 35,000 words of the new novel in this short time and with all your discomforts. It is a great achievement.

Max Reinhardt to Georgette Heyer, letter, 31 December 1969

.

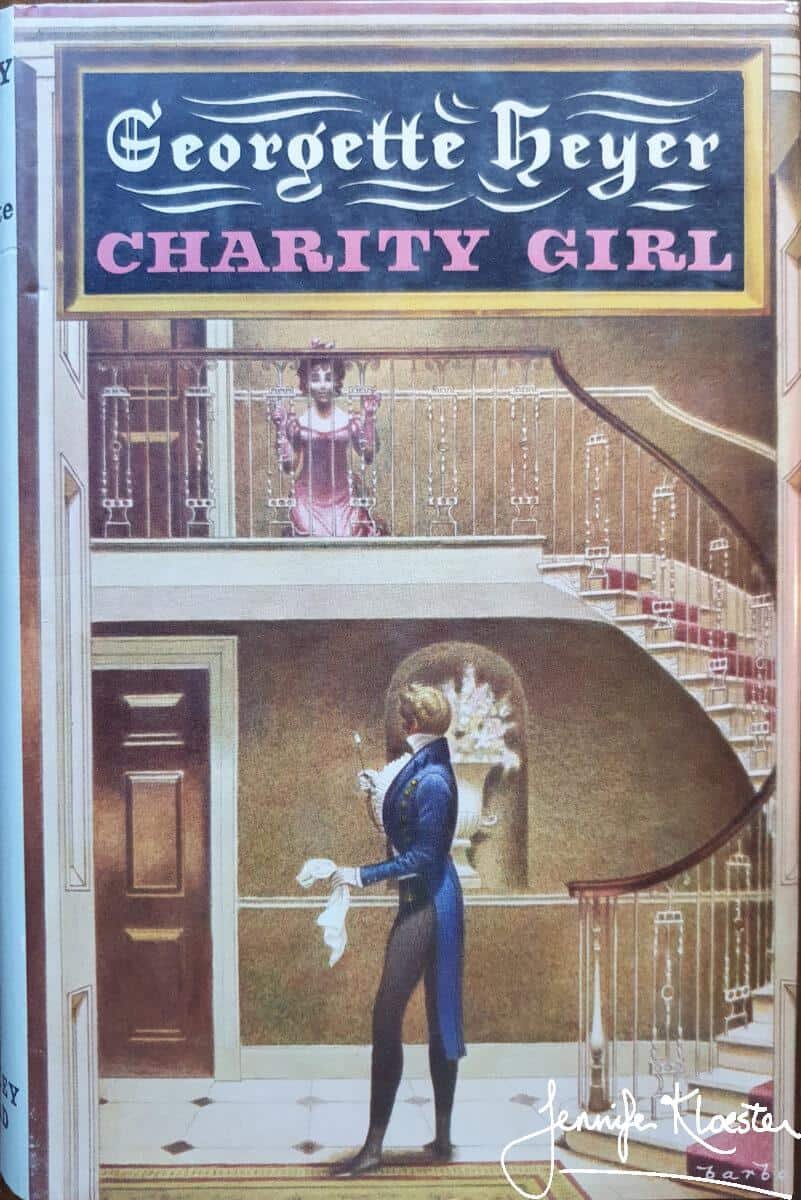

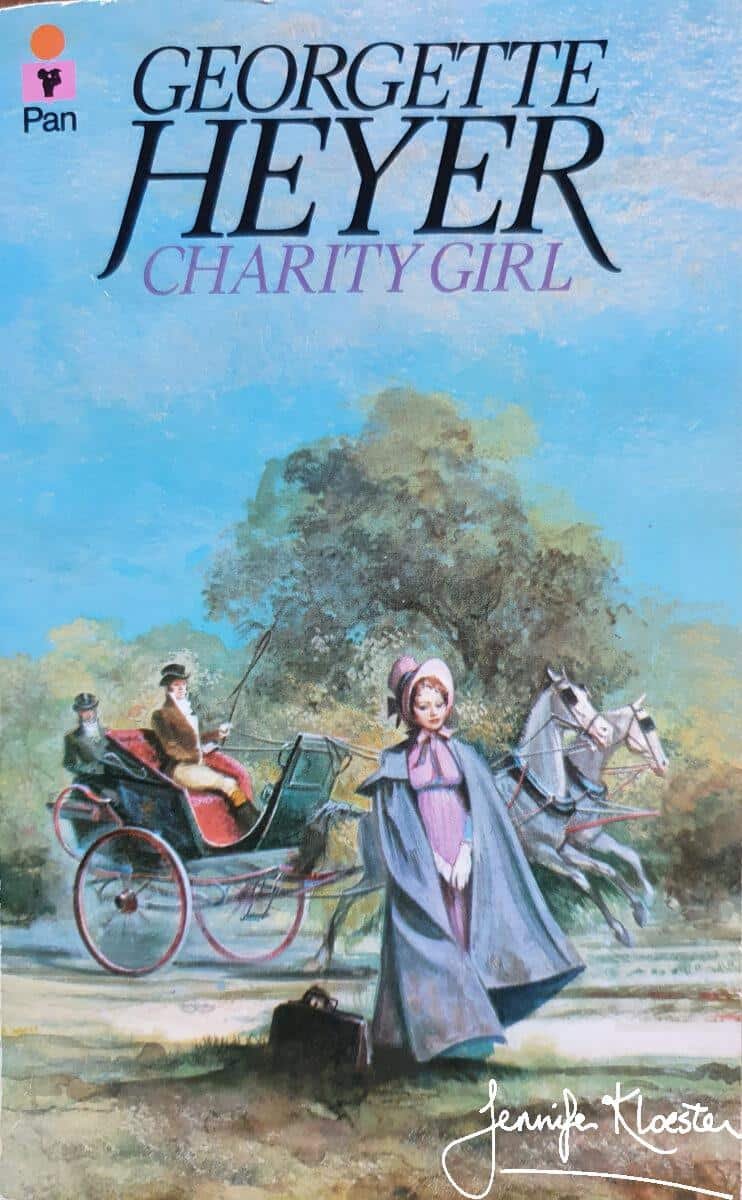

Early in the new year she was back on her feet and issuing instructions about proofs, blurbs and not wanting to see her illustrator, Barbosa, about the jacket until she was ready. By the end of January 1970 she had written 60,000 words and told Reinhardt that: “I hope to deliver the typescripts into [your] hands before the end of March. Provided I don’t succumb either to ’flu, or to one of my Queer Turns, this should be safe enough.” Remarkably, and contrary to her expectation that she would not finish it until March, – “because my health is a bit precarious, and I find I get tired much more quickly than I used to” – Georgette completed the manuscript in mid-February! It seems incredible that even under duress and beset by colds, coughs and “Queer Turns”, as she called them, she could still write a book in just over three months. She proudly told her publisher the title was Charity Girl and the period: “towards the end of the second decade of the XIXth century” Max wrote to her from Barbados to congratulate her, and in her usual style, Georgette simply replied: “I hope the Fans will like the book, but one never knows.”

Regency argot

There is a good deal of quiet humour in Charity Girl and the real heroine of the story, Hetta, is one of Heyer’s clever young women: perceptive, tolerant, kind to her difficult mother, and fully alive to the realities of her situation. Of course, she has been in love with the hero – her “best friend” and co-conspirator -for years but, aware that Ashley does not share her sentiments, she has (for now, at least) accepted the role of spinster daughter, living at home and managing the household to the best of her very considerable ability. Her family is not easy, whereas in Ashley’s family, the Carrington’s, Georgette created one of her truly happy families. These are very real people and the relationship between the siblings is a delight. Even Ashley’s father, the Earl of Wroxton, laid up with gout and in the very first scene irascibly ringing a peal over his eldest son’s head, is, behind all the bluster, a kind and caring parent. It is easy to see why Georgette confessed to enjoying these first few chapters. The conversation between father and son is a delight and replete with some of the glorious language that was one of the hallmarks of her Regency novels. Given that Charity Girl was Georgette’s twenty-fifth book set in the era, it is almost surprising to find the novel so replete with Regency slang. It seems she has been having fun “digging up” some more delightful Regency argot – perhaps dipping into The 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue or Eric Partridge’s A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English or re-reading contemporary Regency sources. Some of the phrases are new to Heyerdom and all of them are delicious as we may see from just a few examples:

- A skitterbrain, a slibberslabber here-and-thereian, a rubbishing commoner! A damned scattergood!, a shuttlehead, p.6

- A jerry-sneak p.39

- A rake-shame p.67

- Conflabberation, bedoozled, a jack-adams p.67

- Easy over the pimples, a spoon p.67

- A scattergood p.68

- A lobcock p.69, a non-plus

- Comfumbuscated p.74

- A great gun, true as touch, a right one, brass-faced p.77

- Mingle-mangle p.91

- Rather of the ratherest, a stretch-halter p.93

- A snippety thing, a regular go-by-the-ground p.104

- A purse-leech p.105

- Surly-boots p.114

- A pigeon-fancier p. 133

- A gull-catcher, a slip-gibbet, a nail, p.134

- Jackanapes, rush-buckler p.143

- Hog-grubber! A flea-mint! P.184

- Noddicock, a souse-crown p.186

- Snivel-nose p.187

- Gripe-fisted, a muck work, a lobcock, a spill-good p.188

- From Charity Girl (Pan 1976)

Masterly portraits

Although it does not achieve the heights of Heyer’s superior plotting or one of her brilliant imbroglio endings, there are many moments that make Charity Girl worth reading. Among these are some of Georgette’s masterly character portraits, including the patriarchal Earl of Wroxton, his younger son, Simon, poor Cherry’s awful father, the flamboyant Wilfred Steane, and his dreadful father, miserly old Lord Nettlecombe. Georgette is one of those rare authors whose secondary characters are as vivid and fresh as her heroes and heroines. Narcissistic Lady Silverdale is one example of a character whose personality is perfectly depicted in just two lines:

.”..since she had never previously encountered Lady Silverdale’s like she did not for a moment suspect that that lady’s plaintive voice and caressing manner concealed a selfishness and a determination to have her own way far more ruthless than the cruder methods employed by Aunt Bugle.”

Georgette Heyer, Charity Girl, Pan, 1976, p.102

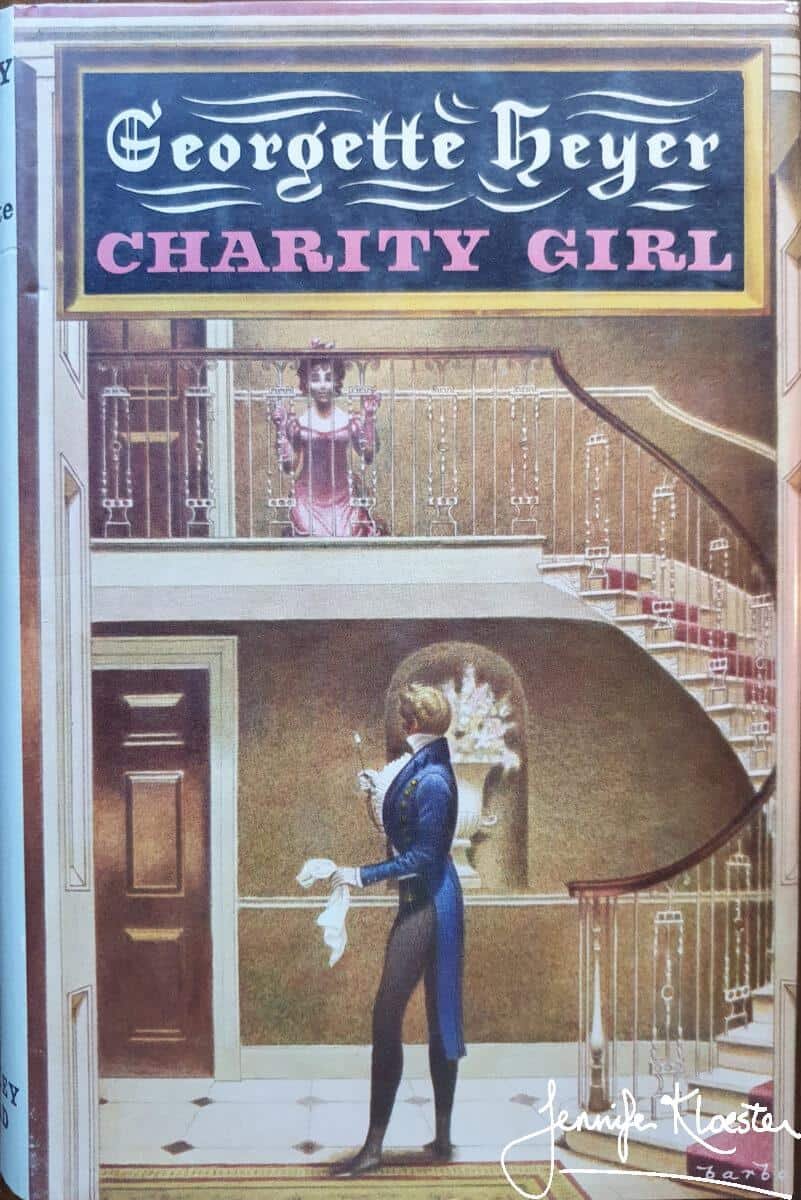

With Charity Girl finished Georgette declared herself ready to see her favourite illustrator: Arthur Barbosa. She had told Reinhardt that “For once in my life I’ve got an idea for a jacket!” It wasn’t quite true, for she had suggested a “sylvan scene” for Cousin Kate and had had ideas for Black Sheep, but this time she had a detailed vision of what the jacket for Charity Girl might look like. Barbosa came to Georgette’s flat in Jermyn Street and they happily discussed her ideas for the wrapper over lunch. She was excited by her proposal and pleased to find that, although Barbosa had his own very distinct style, he was not averse to suggestions. He was pleased to approve her design and a few weeks later sent a draft sketch which only confirmed Georgette’s view that “his work is so exactly right for my stories”.

Belinda McGill

In March, Reinhardt’s former secretary Belinda McGill (née Westcott) sent Georgette a draft blurb for Charity Girl. Belinda had left The Bodley Head soon after her marriage, but in 1970 had been recalled to fill in temporarily for another staff member. She had once written a blurb for Cousin Kate which Georgette had rejected as “too revealing” but Belinda’s synopsis for Charity Girl met with unqualified approval. Georgette happily told her publisher: ‘She’s a clever gal, your Belinda!”. She had always liked his secretary and Belinda admired and respected Georgette – although she also recognised that The Bodley Head’s bestselling author was not infallible. Georgette had never had an editor, but in the later years of her writing life there were occasions when her novels would have benefited from a clear editorial eye. In 1968 The Bodley Head had employed the theatre historian and editor, Phyllis Hartnoll, as a reader for Cousin Kate. She had made several minor suggestions for the novel and told Belinda that “I don’t think I have ever seen a book so peppered with commas.”‘ On reading Charity Girl Belinda herself noted that “the original circumstances described in the first few chapters are very similar to other things she has done, but the climax and the dénouement are different. Of course it will sell, but it’s not one of her greatest, –– and for God’s sake don’t tell her I said so!” Belinda knew better than to suggest changes to Miss Heyer.

On publication in October 1970, Charity Girl went straight to the top of the bestseller charts and Georgette Heyer had yet another huge hit on her hands.