In August 1937 Georgette Heyer completed the manuscript of her Waterloo novel, An Infamous Army. It had been a huge effort requiring intense research and long days of reading and writing and she had loved every minute of it. She had written the manuscript in “meticulous longhand” and then asked her agent to find her a typist who would come and stay at Blackthorns so that she could read her manuscript aloud – “complete with punctuation” – have her typist take it down in shorthand and then type it up ready for the publisher. The typist was Sylvia Gamble, a young north country woman who had declined the opportunity to study at Cambridge and chosen instead to become a literary secretary. Sylvia stayed at Blackthorns for a fortnight and, although she was only twenty-four to Georgette’s thirty-five, they became good friends. Sylvia later described her as having ‘a beautiful brain’ and an ‘ordered intellectual apparatus’ and was in awe of Georgette’s ‘meticulous historical research’ and impressed by how seriously she took her novels. In 1938, Sylvia would accompany Georgette on several of her research trips for her novel of Charles II, Royal Escape, but in late 1937, having dealt with the proofs of An Infamous Army, Georgette first turned her attention to her next detective novel.

“By far the best, wittiest” detective story”

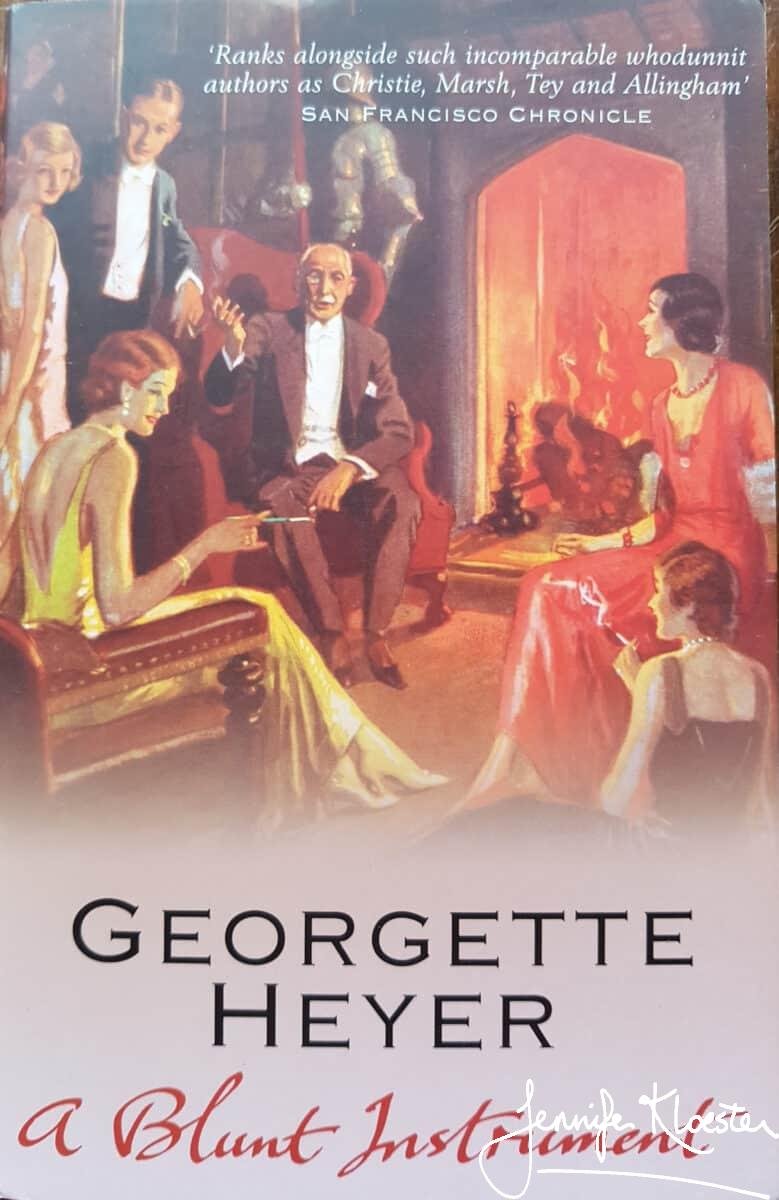

On publication in May 1938 A Blunt Instrument was described by the famous reviewer, Torquemada, as “by far the best, wittiest and, for want of a better term, truest detective-story that Georgette Heyer has yet written”. It was a glowing compliment and Georgette later confessed that she “almost let it go to my head”. Though increasingly self-deprecating about her writing and sometimes asserting that she did not keep reviews, Georgette certainly read and cared about them. She was appreciative of a good review and complimentary of any reviewer she thought perceptive but she was alsowriting accepting of criticism if she thought the reviewer fair. Contrary to popular belief, Georgette Heyer was often reviewed in the major and minor British papers and regularly in the papers in America and Australia. By the late 1930s she had already developed a loyal following for both her historical and her detective fiction.

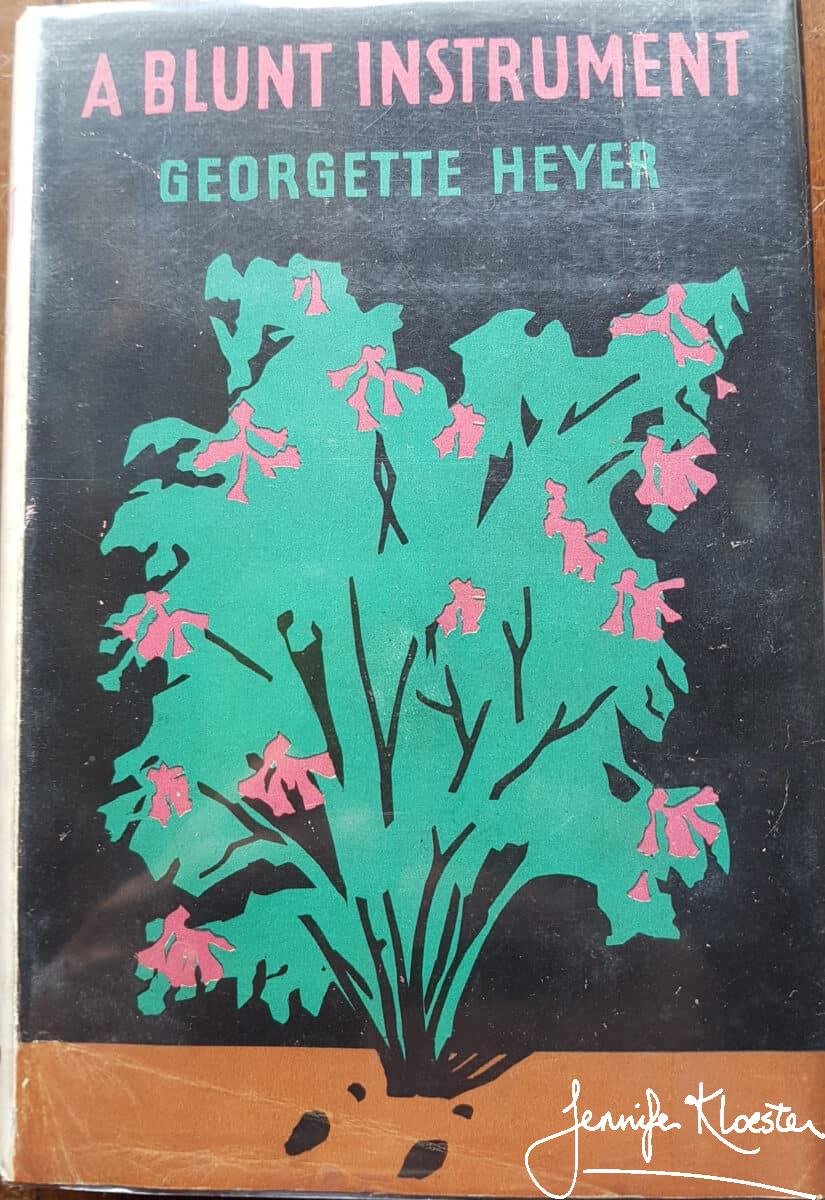

The 1940 H&S “Cheap edition”

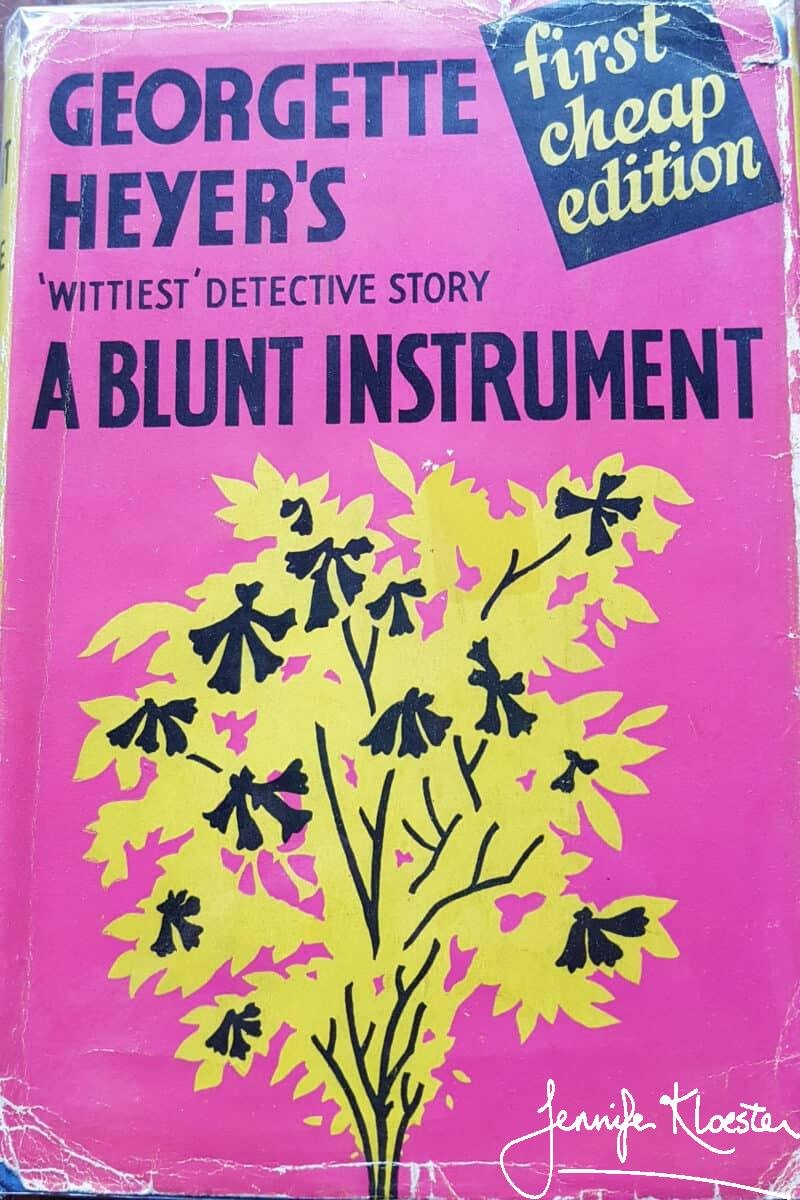

The 1940 H&S Yellow Jacket edition

Ronald “largely responsible for the plot”

Though she had finished writing An Infamous Army in August, Georgette was unable to immediately begin writing A Blunt Instrument because Ronald was busy studying for the next round of Bar exams in October. According to Georgette, it was Ronald who was ‘largely responsible for the plot’ and, athough she had the “general outline” of the novel in her head, she couldn’t send her agent a synopsis until her husband was free to discuss the murder with her. It must have been an interesting and at times challenging collaboration because Ronald and Georgette were so very different in both brain and temperament. While there is no doubt that Georgette Heyer was perfectly able to contrive a murder plot for herself and to execute the detective elements without assistance – after all, Ronald had had no hand inThe Talisman Ring or Death in the Stocks and they were both clever and successful books – he had been a keen supporter of her writing since their marriage in 1925. He obviously took delight in “hunting up” unusual details, finding elusive bits of research, making suggestions and he always read her manuscripts. It was Ronad’s response to the drafts of whatever she was working on that told Georgette whether she was on the right track or not. The challenge, however, in having Ronald devise the murder method for her detective novels lay in his having no idea about character or relationships. According to their son Richard, Ronald would say something like: “A does this and then B kills him and then A does that” only to have Georgette say “Oh no, A would never behave like that” . In her 1984 biography, Jane Aiken Hodge asserted that:

‘Harnessed to his plots, however technically sound, her genius was inhibited, and it showed. There is a failure of homogeneity in these books, with character too visibly giving way to plot.’

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, p.50.

“Delicately pointed wit”

“Georgette Heyer, in A Blunt Instrument, gives a brilliant display of the most delicately pointed wit: she can be guaranteed to keep you in fits of laughter…”

Nicholas Blake, “Romance of Detection”, The Spectator, 17 June 1938

Ronald finished his Bar exams and in mid-January 1938, Georgette began writing her seventh detective novel. She originally called it “Blue Murder” and easily produced the first 10,000 words, telling Norah Perriam that ‘some of it [is] quite funny. You’ll be glad to hear that the corpse is discovered on the first page, & there is no assembly of characters to be sorted out.’ On finding that “Blue Murder” had already been used, Georgette changed the title to A Blunt Instrument – a remarkably apt title though the blunt instrument remains genuinely elusive for much of the novel. Another three chapters quickly followed the first 10,000 words and by 10 February she had finished the book. She sent the manuscript off to her agent and, in a style that was becoming increasingly self-deprecating, told Norah Perriam that she was sick of the book.

‘That’s all – DO your best for me! I make it about 72,000, but better get the typist’s estimate. Let me have it back to correct as soon as you can! I’m sick of it

Georgette Heyer to Norah Perriam, letter, 10 February 1938

Incredible

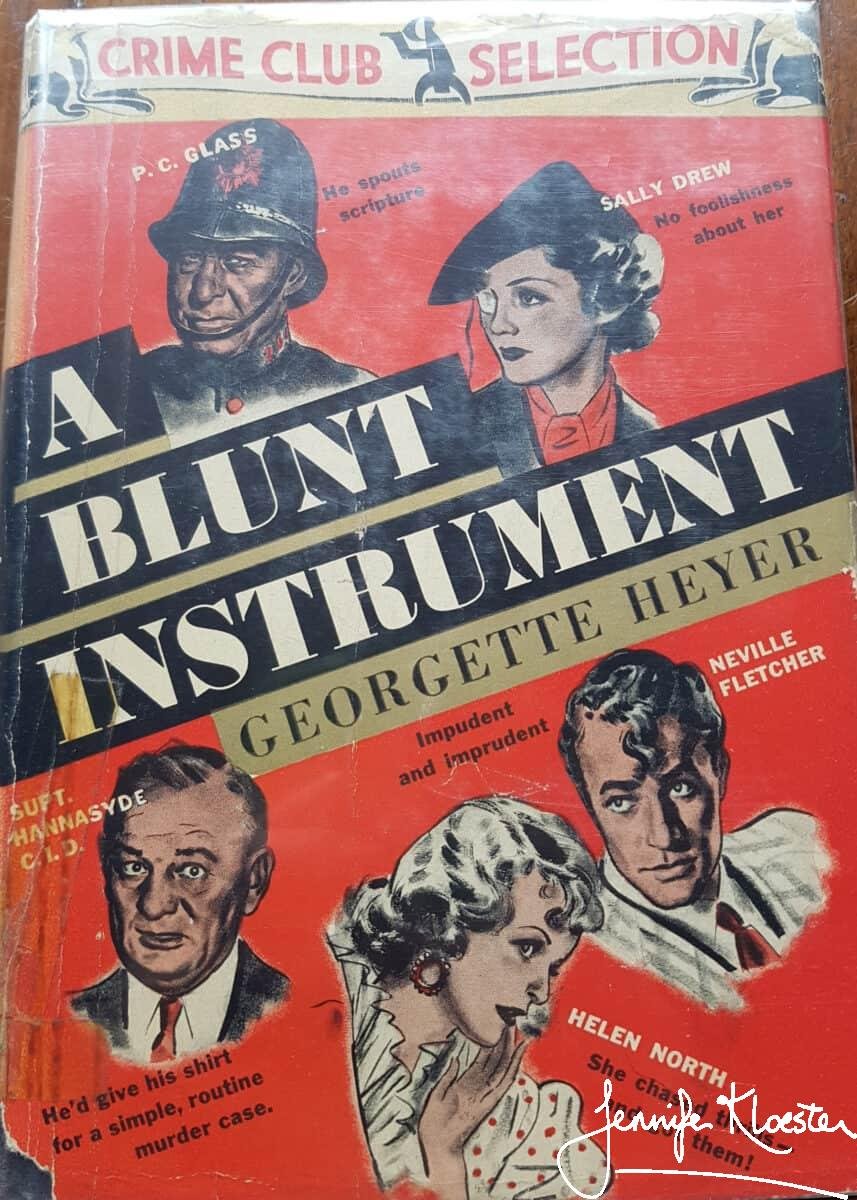

It seems incredible to me (who takes a year to write a novel and took four (!) years to write Jane Austen’s Ghost) that Heyer was able to write so many of her novels in a matter of weeks. What a mind she must have had and what a memory! And her detective novels are so often funny. And in A Blunt Instrument her humour is no less evident for the speed with which she wrote it. Reviewers were quick to acknowledge that Georgette Heyer was a crime writer whose sense of humour set her novels apart from most detective fiction. A Blunt Instrument is a very funny book in places with some brilliant characterisation and dialogue and for many readers the murder is a genuine mystery. James P. Devlin described the novel as her “masterpiece” and there is no doubt that her creation of Malachi Glass, the mournful, bible-quoting policeman, who turns up at all the wrong moments, is masterful. His encounters with Sergeant Hemingway are a delight and the contrast between PC Glass’s insistence on quoting reproving Old Testament scriptures and Hemingway’s fascination with modern psychology is great fun.

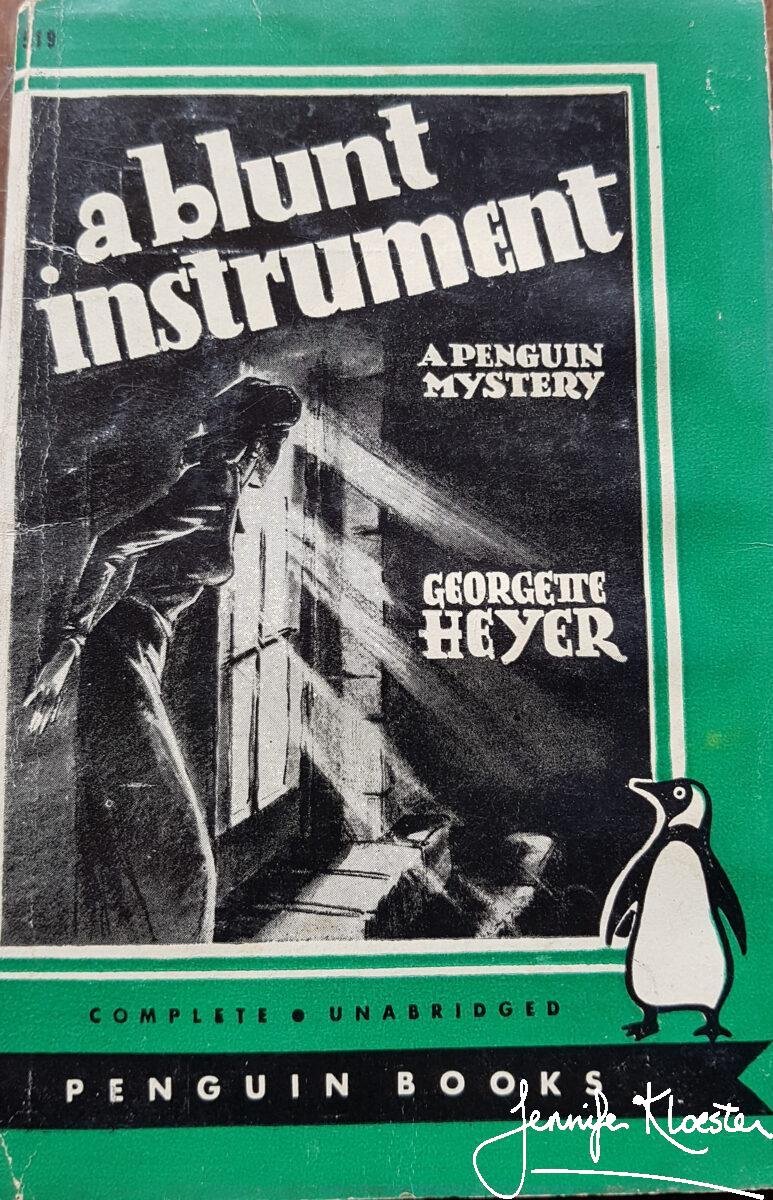

First published in April 1943 in the Penguin edition

It had already been reprinted twice by March 1944

“Spirited dialogue”

“The pleasure of reading her spirited dialogue and meeting her enterprising characters is not affected by an early guess at the solution.”

Eric Partridge, “Deteection”, The New Stateman and Nation, 25 June 1938.

My favourite character in A Blunt Instrument. is Neville Fletcher, nephew of the murdered man. Neville is one of those delightful characters who would perform as well in a Wodehouse or Sayers’ novel. He is deceptively vague, unintentionally charming, an adventurer, and a suspect in his uncle’s murder. While not loving everything about A Blunt Instrument., I do love Neville, and with her usual expertise, Georgette gives him some very funny as well as very perceptive lines:

“As well as one person may know another, did you know your uncle?”

“No. Interest being the natural forerunner to understanding.”

“You’d none in him?”

“Nor anyone, ‘cept objectively. An’ I’m not sure of that either. Do you like people?”

“Don’t you?”

Neville spread his hands out, slightly hunching his thin shoulders. “Oh, some—a little—at a distance.”

Superintendent Hannayside speaking to Neville Fletcher in A Blunt Instrument, H&S, 1938, p.57.

Perceptive

This delightful comic exchange is both very funny and perceptive. I have also wondered if it offers readers a moment where Georgette Heyer is revealing a little more of herself and giving us a tiny insight into her fierce proclivity for privacy. She did not always deal well with people. Nor did she suffer fools gladly. She was also intensely shy and, despite having a formidable presence, underneath she often struggled in company, once telling her aunt that

“I am a total loss at social functions, being ready to run a mile (almost) rather than go to a party, especially a literary one.”

Georgette Heyer to Alice Bowden (nee Heyer), letter, 20 April 1940.

Whether it reveals something of the deeply personal Georgette Heyer or not, A Blunt Instrument, is an easy read with a clever murder mystery and another of her satisfying Hannayside and Hemingway detective stories. Years after writing it, even Georgette remembered good things about the novel:

‘”Torquemada”, who used to review the [’til] fiction for the Observer, went all out for A Blunt Instrument, and headed a five-column patch in the paper, in fat, black Caps, “The Heyer Direction”, putting me at the top of his list. I never preserve reviews, but I do remember that this one stated: “This is the best, and for want of a better adjective – the truest of Miss Heyer’s detective novels.” I almost let it go to my head!’

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callender, letter, Heinemann Archive, 27 January 1954.

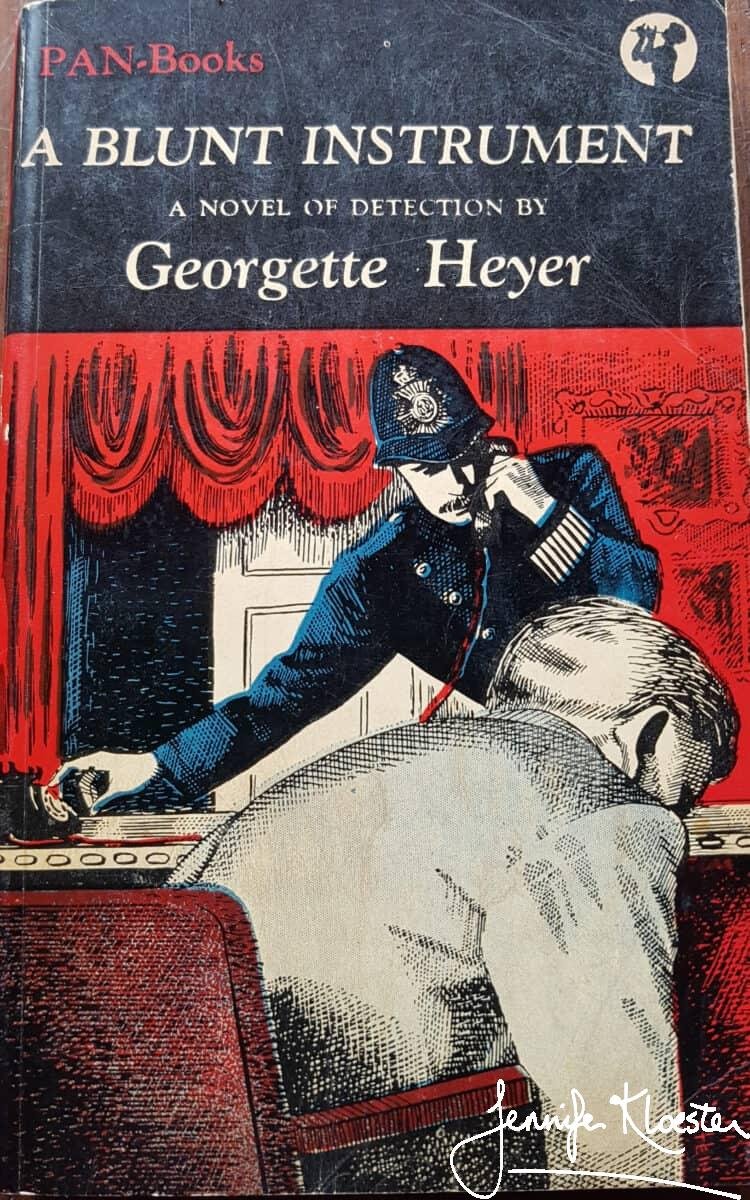

The 1949 Pan edition

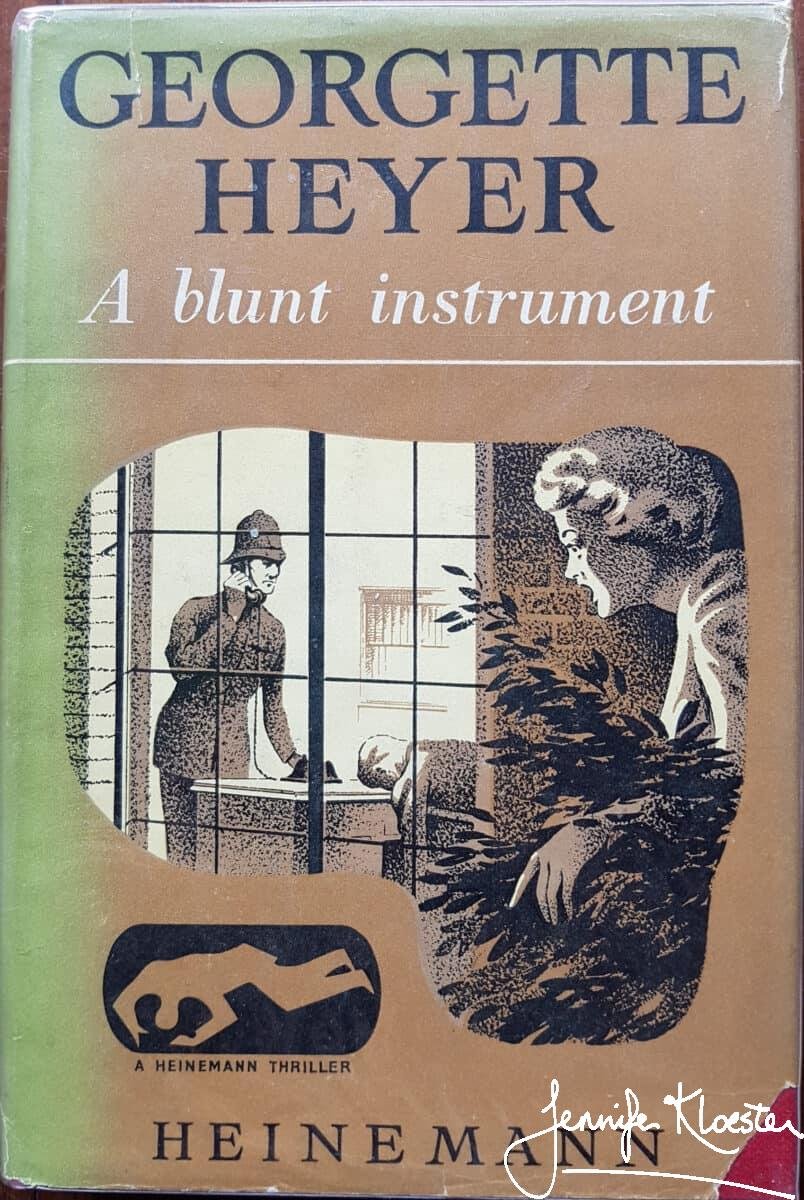

Number 5 in the 1954 Heinemann Numbered Series edition