Myths and legends are pervasive things that, once they take hold of the public consciousness, are almost impossible to remove. For those who read and love Georgette Heyer’s many novels there a couple of myths that have proved very difficult to shatter. One of these is the idea that she did not want her books made into films (so wrong!) and the other is that her 1942 detective novel, Penhallow, was deliberately written as ‘a contract-breaking book’ when it was actually a book she believed in utterly and which she felt compelled to write. Originally called Family Affair, the novel that became Penhallow would be a book that, not only obsessed Georgette Heyer, but was also a book that she, her agent and her eventual publisher believed to be a tour de force. She held the highest hopes for a great success with big sales and excellent reviews and told her agent that ‘if obsession counts FAMILY AFFAIR ought to be amongst my best books.’

Struck with the idea

Georgette had first been struck with the idea for the novel in May 1941 when she should have been writing the book that became Faro’s Daughter. As she explained to her agent:

The most amazing & unexpected thing has happened! While I was meditating on Pharaoh’s Daughter, a wholly unwanted saga about a preposterous family called Pendean, who live at Cressy Hall, crept into my mind, & grew, & grew, & grew. Finally, the family tree spread so, & such ramifications grew up that I set it all down, with a genealogical table attached. My dear L.P., I don’t know yet all the details, but Ambrose Pendean was murdered, poisoned, & he was a roaring, Rabelaisian old man, a real patriarch, with roaring Rabelaisian sons, & two who are Lilies of the Field, & a brother who has soft white hands, & collects jade, and a widowed sister with a wig, & foul language, trailing dirty skirts through the vast spaces of Cressy Hall … It seems to me that the thing is called Family Affair, & possibly set in Cornwall. Only you don’t hunt much in Cornwall,* do you, & the Pendeans obviously do. It will be long, obviously, & more of a problem in psychology than in cold detection.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 28 May 1941.

She continued in this vein for another two full pages, describing the rest of the extraordinary family to Moore, before ending her letter with a message for Percy Hodder-Williams, her publisher at Hodder & Stoughton:

Next time Uncle P. gets restive, tell him that this thing burst on me, willy-nilly. I even dreamed about the Pendeans last night! I shall have to keep a note-book for them, as fresh imbroglios keep cropping up, & mustn’t be forgotten.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 28 May 1941.

She was eager to get the book on paper but was committed to writing Faro’s Daughter for Heinemann first. Frustratingly, it would be some months before she began the only one of her novels to ever psychologically obsess her or raise her hopes of extraordinary success. She could not know that Penhallow would change the course of her writing career.

Another new home

In September 1941 Georgette and Ronald moved again – this time to 27 Adelaide Crescent in Hove, a few miles further west along the Brighton waterfront from Steyning Mansions. Their new home was a small service apartment on one floor of an elegant, curving row of three-storey white terrace houses with views across the sea. Their building belonged to the famous Sassoon family and had a beautiful black and white marble hall with an elegant wrought iron staircase and a handsome drawing room. To Georgette’s great relief there were no cooking facilities. Instead, all the tenants’ meals were brought up to them by staff overseen by Mr and Mrs Banton, who ran the building. Isabella Banton admired Georgette tremendously and later told Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, that she was a ‘marvellous person’ and that ‘there was nothing she didn’t know’. The two became great friends and on one occasion during the War, when there was alarm that Hove was going to be cut off and all of the staff left the building, Mrs Banton took Georgette’s dinner up to her. Unfortunately, she dropped the lot, but Georgette took it all in her stride, helping to clear up the mess and replace it. Long after Georgette and Ronald had moved to London, she and Isabella continued to correspond and would sometimes have lunch together in town. Georgette’s last letter to Isabella Banton was written only a few months before her death in 1974. Years later, Mrs Banton vividly recalled those months in Adelaide Crescent, when Georgette would sit ‘at the side of the fire writing on her lap and living with real people’. These were the Penhallows.

Penhallow

Penhallow, the novel Georgette would eventually write in 1942, would be unlike anything she had written before or would ever write again. It stands alone in the Heyer canon. Part murder mystery, part family saga, part pschological experiment, when she finally came to write the book about which she had thought for months, Penhallow poured from her pen.

Let me tell you that with the exception of a handful of passages first jotted down in pencil in a rough note-book, as you see it, so it came out of my head.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 29 May 1942

It is a dense, wordy novel, rich in description and alive with the sounds, smells and scenes of Trevellin, the great, ramshackle house on Bodmin Moor in which her large and ‘preposterous family’ – the Penhallows – live. These were the people who came alive for Georgette while she wrote her strange, and strangely compelling, novel. Each servant and family member is fully-fleshed out with all of their anger and resentment, their worries and secrets forming the complex core of the book. One of the things that sets Penhallow well apart from Heyer’s other novels is the sense of unpleasant realism. Today, we would describe the family as ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘toxic’ and it is a testament to Heyer’s skill that this visceral book is not without its humour.

Penhallow is a fascinating psychological study, not only because of its characters, but also because of the way in which it possessed Georgette Heyer’s mind as it did. Jane Aiken Hodge described Penhallow as ‘a strange, grim book’ and that it showed

more signs of strain than can be accounted for by war and trouble with agents or publishers. This was a bad time in Georgette Heyer’s life, the nearest she ever came to a breakdown.

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Pan, 1985, p.66

Aiken Hodge was wrong about Heyer’s mental state – her breakdown had occurred ten years earlier – but she was right in thinking that Georgette had been under strain – at least in the months leading up to her writing of Penhallow.

Arsenic!

Although she had promised Hodder that she would get to work immediately on Family Affair and the novel was burning in her brain, the book languished through November and December 1941. Georgette had been suffering from an unpleasant skin condition and towards the end of October had begun a treatment prescribed by her doctor. Unfortunately, it had only made her worse:

‘Herewith the contract. I haven’t read it, being too ill to care! I have been taking a cure for a skin-complaint – increasing quantities of arsenic. I cannot describe to you the horror–! I have been in bed for a week, wholly unable even to sign my name. Better now, having jettisoned the cure.’

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 31 October 1941.

It took time to recover from the arsenic treatment and she remained ‘under doctor’s orders’ for some weeks, describing herself as ‘suffering from Aftermath, which includes such oddments as weakened heart, abnormally low blood-pressure, and blurred sight’. Things were no better in the new year, and Georgette still had not begun the novel she longed to write. Ronald’s mother died on 31 December 1941 and the final weeks of her life had caused Georgette deep emotional anguish as she watched her mother-in-law grow

steadily weaker, lying in a coma, and altering under our eyes. You may imagine what sort of time we went through. She died in her sleep, but not before Ronald had been sent for – the day before – on a false alarm, and not before he, I, and her sister were worn to shreds with the anxiety, and the strain of waiting for an end which was inevitable from the start. None of this exactly helped me to recover my health, and I am today a sort of semi-invalid, but beginning at last to feel a little more alive, and able to cope.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 7 January 1941

By March 1942, she still had not begun writing her Cornish saga and told her agent that ‘the Penhallows are seething in my brain, and if only I could have a month’s peace and quiet I could get them down red-hot onto paper.’ Unfortunately, Georgette had not long recovered from an attack of shingles when her young son, Richard, contracted whooping cough, to be followed only a few weeks later by Ronald who succumbed to a nasty case of ‘flu-cum-tonsillitis’. A month’s holiday at Cleeve Hill saw Georgette and Ronald in better health but Richard had not recovered and would not return to school for the rest of term. There is no doubt that these sorts of health and domestic challenges put a strain on Georgette, but I believe that something else drove her to write Penhallow. Years later, her son Richard would suggest that the novel was ‘a catharsis of her family’. It is an interesting idea. Georgette was in her fortieth year and Penhallow may have been a symptom of what has come to be called ‘a mid-life crisis’. She herself often puzzled over the book, not knowing why it obsessed her as it did. She once described the novel as ‘a very peculiar, long and unorthodox story’ and wondered ‘Why on earth did I have to write this disturbing book?’ She had no clear answer. All Georgette knew was that even if it were a ‘mistake’ she had ‘got to write it’.

It’s no use begging me not to write this book: these astounding people have been maturing in my head for months – a sort of saga, which gets added to, and embroidered every day. I know everyone of them intimately. You’ll have to assure Uncle Percy that however repulsive my characters may be, my treatment of them is Pure as Driven Snow. It will be damned funny, too, particularly when Hemingway gets going in the midst of this Cold Comfort Farm circle.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 14 March 1942.

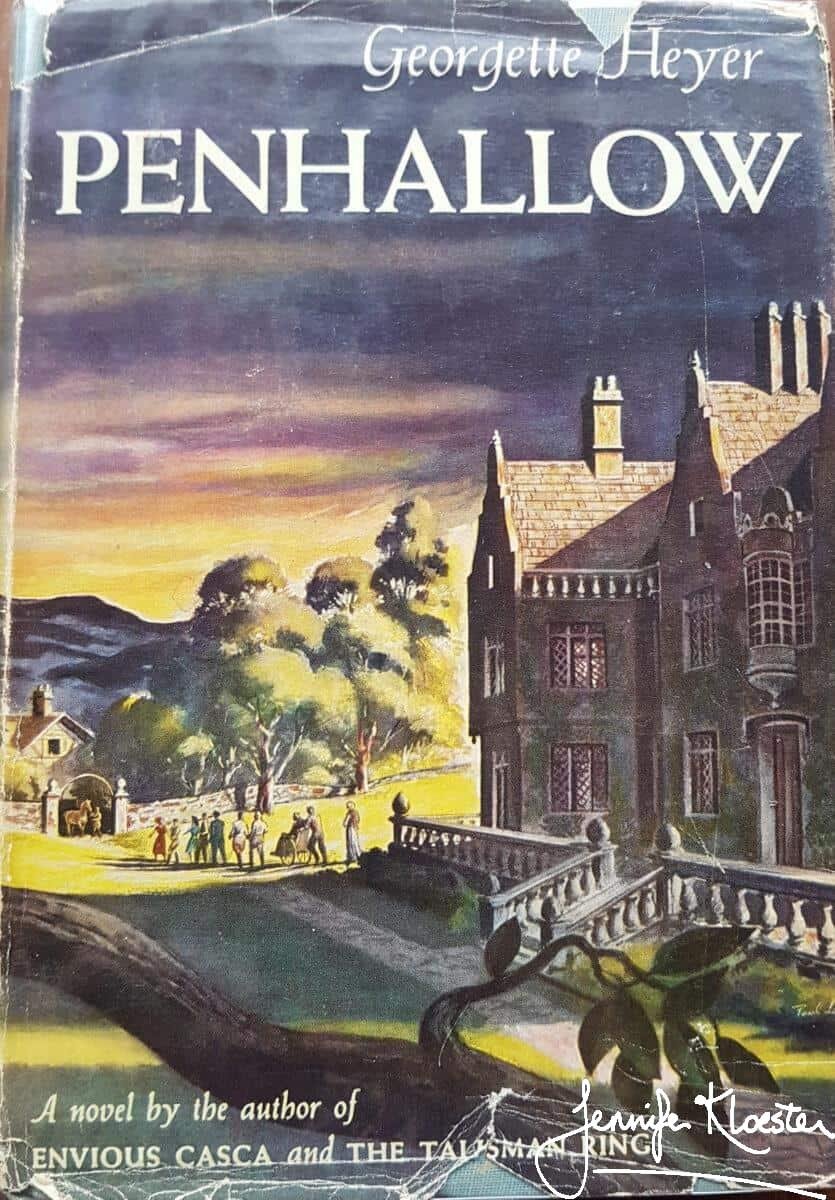

The 2006 Arrow edition of Penhallow

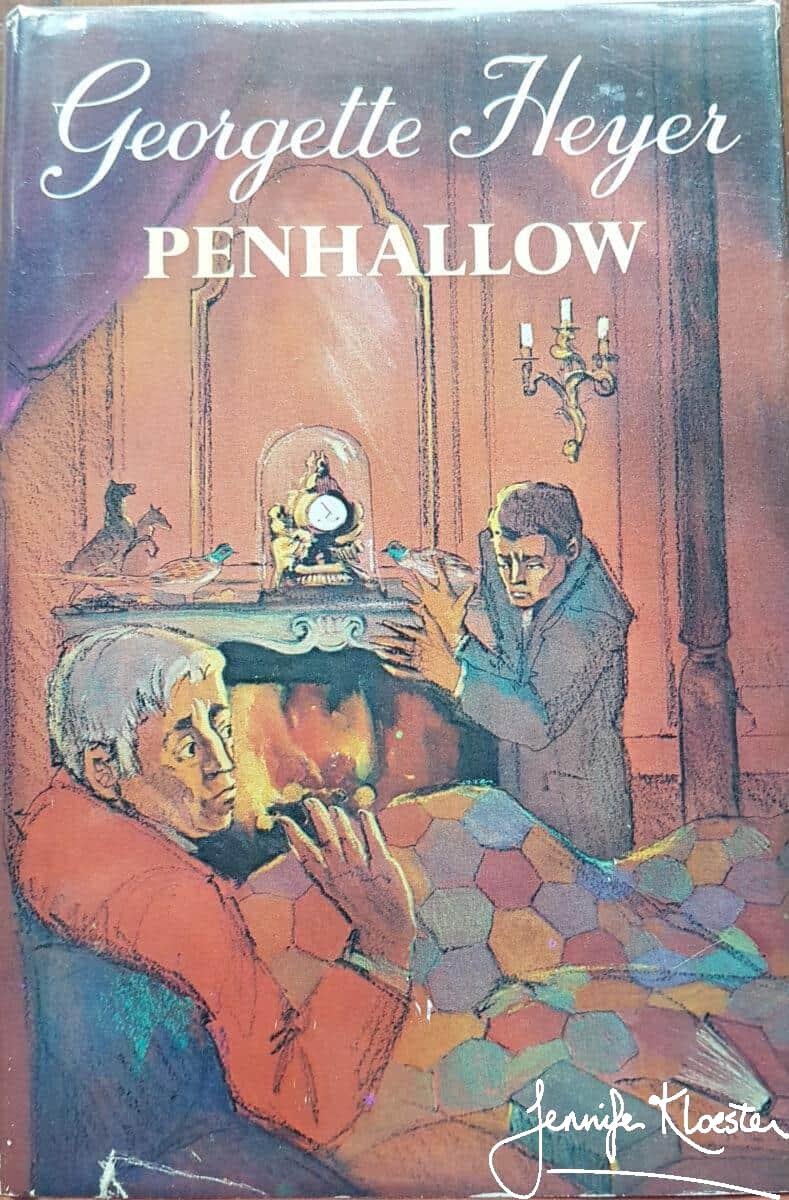

The US 1971 Dutton edition of Penhallow

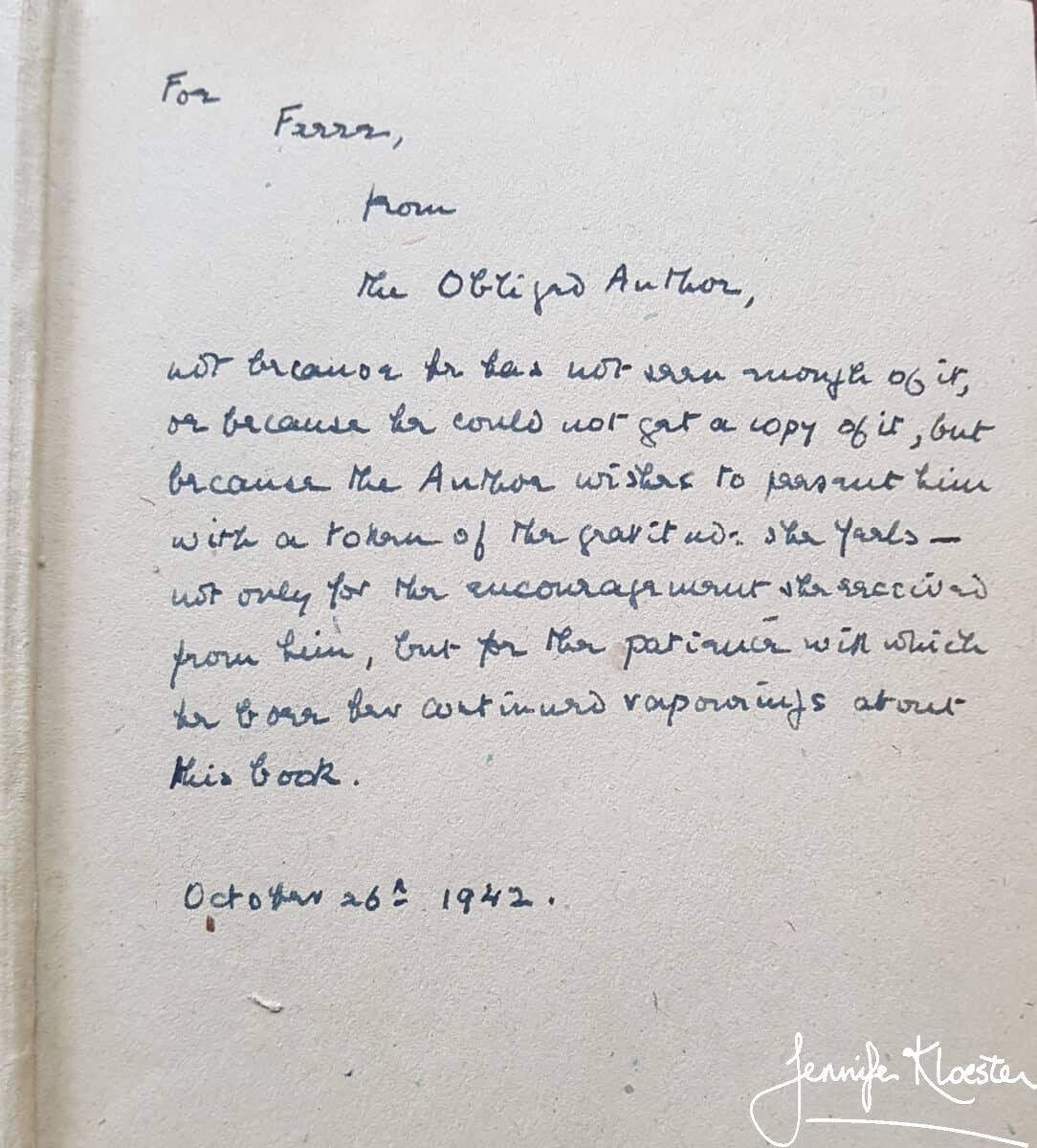

“For Frere”

In the end she did not use Inspector Hemingway in the novel but created Inspector Logan, a character she would never use again. The element of detection in Penhallow is in many ways a distraction from the real story and Georgette herself said that ‘Of course, I ought to have given it an eighteenth-century setting, and have ruled out the element of detection, but I can’t do it now: these people ARE, and it’s not a bit of good trying to alter them to fit another period.’ This was not going to be one of her usual country house murder mysteries. In fact, there is no actual mystery for the reader to solve. We watch the murderer commit the crime and see how the tyrannical old patriarch’s death changes everything. Penhallow is intentionally Shakespearean in showing how a desperate act intended to bring about good consequences instead brings only more tragedy in its wake. It is not surprising that Georgette uses a quote from Measure for Measure at the beginning of the book.

She finally began writing Penhallow at the end of March and finished the book two months later at the end of May. Georgette wrote more letters aboutPenhallowi than any other book. Before, during and after its composition she wrote frequently to her her agent and to her friend, A.S. Frere of Heinemann. the letters reflect her growing conviction that Hodder & Stoughton – the publisher to whom she was meant to give this latest book – would not want to publish Penhallow. The opening line alone – ‘Jimmy the Bastard was cleaning boots – she felt would be enough to put off the devout Christian, Percy Hodder-Williams. She was right. H&S rejected Penhallow and Georgette triumphantly offered it to Heinemann. Frere had long been a fan of the novel and eager to publish it, assuring her that it was ‘her best yet’.

For Frere,

From the Obliged Author,

Not because he has not seen enough of it, or because he could not get a copy of it, but because the Author wishes to present him with a token of the gratitude she feels — not only for the encouragement she received from him, but for the patience with which he bore her continued vapourings about this book.

October 26 1942

Georgette Heyer, hand-written dedication on the fly-leaf of Penhallow,, October 1942.

Love or hate Penhallow

Time has proven that Penhallow is not Georgette Heyer’s best book, but it is a novel worth reading – especially when one knows just how powerfully it obsessed its author. In Madeline Paschen’s brilliant essay, “The Mystery of Penhallow” she gives the reader a kind of ‘before and after’ view of the novel in light of the longstanding myth of it being a contract-breaking book. It was not a contract-breaking book, but perhaps the story became a useful rationale for the only novel to so deeply disappoint its writer after publication. Penhallow had held its author in thrall. She fervently believed it would ‘sweep the board’; that it would make people sit up and take notice. It did not. Penhallow was successful in that it sold well, but it was not the huge bestseller she had believed it would be. She had held such high hopes and had written such eager, confident letters full of ideas and feelings about the book that its ‘failure’ must have hit her hard. Madeline Paschen sums it up well:

I do believe that something crucial happened to Heyer as a writer in that year between the two books [Penhallow and Friday’s Child]. Penhallow, regardless of its critical failure, was a passion project for Heyer, and showed her flexing her writing muscles outside of the genres where she’d already established herself. Whether you love or hate Penhallow (and arguments can be made for both interpretations), what cannot be denied is that it represented a crucial turning point in Georgette Heyer’s career. It deserves much more recognition and acclaim – certainly more than the “contract breaker” role in which it has been unfairly placed in the popular consciousness.

Madeline Paschen, ‘The Mystery of Penhallow’, in Heyer Society: Essays on the Literary Genius of Georgette Heyer, Overlord Publishing, 2018

* People do hunt in Cornwall, though not as much as in some other counties. Today there are four main hunts in Cornwall: the Four Burrows Hunt at Carn Brea, the Western Hunt at Madron, the Cury Hunt at Helston and the North Cornwall Hunt at Camelford.

4 thoughts on “Penhallow – NOT a contract-breaking book”

I would agree with Richard’s comment of Penhallow being a ‘Catharsis of her family’: all that ill health, bereavement, changes in home, his mother’s commitment to her writing (and it’s financial benefit to the family). The obsession with writing the book, the ‘have to do this’, and the way the story and characters inhabited Heyer’s dreams seems a giveaway of the turmoil inside her.

I have written as a form of ‘getting it out of my head’ for years. I liken it to getting my whirling thoughts, confusions, worries and emotions off the hard drive of my mind’s computer. Particularly good release when one saved documents on those old floppy disks, you could physically take them out and store them in a container, and you saw your RAM level increase.

By the way no best seeking novel has arisen from all those journals of mine… as yet anyway 😉

Interesting that Ms Heyer was so pleased there was no kitchen in the new home – she didnt have to pretend about not wanting to cook, she could get on with the business of getting those books out of her head and on to paper.

Thank you very much once again, Jennifer.

Years ago I tried–and failed–to read PENHALLOW. Never having made a second attempt, I can’t discuss its merits or demerits. But as a writer I can sympathize with GH’s obsession with a book. My first novel (fourth to be published), STOLEN WATERS, was based partly on tales of my mother’s ancestors in Grand Cayman and partly on a vividly disturbing dream. I literally felt compelled to put it down on paper. It’s different from anything else I’ve written: dark, ultra-romantic and occasionally starkly realistic. The setting on a regency-era sugar plantation in the Caribbean is only one of its quirks. I definitely would not attempt anything similar again, and more than one reader has found it disturbing or offensive. A reviewer commented that none of the characters are likeable–which I took as a backhanded compliment! The genesis of such books is often highly personal, as is the response of readers. With PENHALLOW, I must admit that had it been the first Georgette Heyer novel I picked up, it would almost certainly have been the last as well!

Hi Paul

What a fascinating story and I can definitely see the parallels with Heyer’s Penhallow. It’s interesting how for some authors a book can pick them up by throat and not let go until the last word is written! As you say the genesis of such books can be highly personal and I suspect often very deep-rooted. I believe this was the case with Heyer too. I’m so glad that Penhallow wasn’t your first Heyer or you would have missed out on so much! Thanks for posting.

Such a fascinating post, I love how you’ve clarified the details about Penhallow and its place in literature. It’s always interesting to see how different books are perceived, especially when there’s so much historical context and personal influence behind them. Your insights into the book’s themes and its importance really shed light on why it’s so impactful. Thanks for sharing your thoughtful perspective.