From house to flat – the move to Brighton

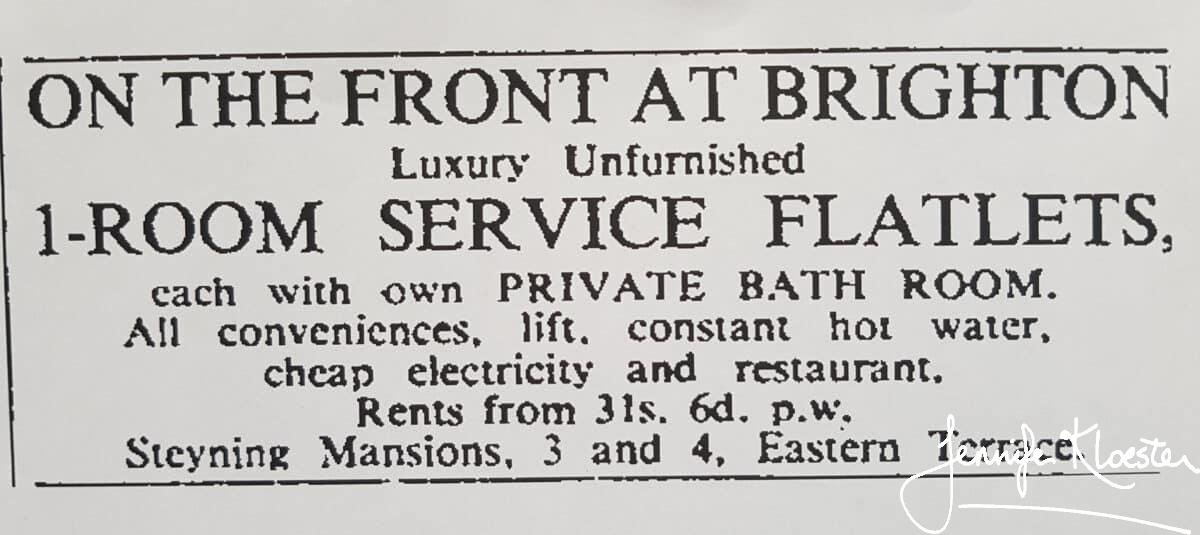

Just before Christmas 1940, Georgette and Ronald, with their eight-year-old son, Richard, left Blackthorns, their home for the past seven years, and moved to Brighton. Heyer had written a dozen successful novels at Blackthorns but the Second World War had changed many things and she and Ronald could no longer cope with such a large house. She had grown up in a world where domestic servants were an unquestioned part of life and, as an author and the mother of a young child, servants had been a vital support – allowing Heyer to write for as often and as long as she needed without having to think about cooking or cleaning or childcare. One of the most lasting changes brought about by the War was the dramatic shift in employment – especially for women. Many housemaids, cooks and housekeepers were easily tempted away from the drudgery of domestic service to the better-paid-with-better-hours work on offer in factories, public transport or on the land. With bombs falling on Sussex with nerve-wracking regularity, Georgette and Ronald had decided to send Richard away to the Elms, a boarding school in the much safer Malvern Hills. His absence during term time enabled them to move into a service flat with meals provided and regular cleaning. Georgette would be able to manage the household without the need for a maid or cook-housekeeper. On 19 December 1940, the Rougiers began the next phase of their life in a service flat at Steyning Mansions opposite the sea at Brighton.

A new historical romance…

By April 1941, Georgette was well settled into her new home with plenty of time to write. Meals were provided, Richard was safe at school and, when not performing his duties as ‘Gas Company Instructor, Bombing Instructor, & No. 1 Sniper’, Ronald was commuting daily by train to his chambers in London. She was now coming to the end of Envious Casca, her latest murder mystery for Hodder & Stoughton, and had already had an idea for her next book. A.S. Frere, her friend and publisher at Heinemann (now doing War work for Ernest Bevin), had recently been to stay and Georgette had told him that she would have a new historical romance ready for Autumn. Frere had been enthusiastic and urged her to have it ready by the ‘End of August, latest.’ Georgette had agreed, at which point he had immediately said, ‘What I really meant, was the beginning of August.’ Her reputation for producing quality work quickly had become well-known in the firm, but even for Georgette the beginning of August seemed too tight a deadline, and she firmly told Frere, ‘nothing doing’. Two weeks later, her idea for the new book had begun to crystallize and she wrote to her agent to say:

Must talk to you about my new book. No, not Casca – he’s nearly finished, & nothing to talk about anyway. The new one, I said. Do you recall a short I once wrote, & you or Norah sold to Woman’s Journal for a pittance? Well, it was a poor short, but it has the makings of a novel, & it is going to grow into a lovely romantic bit of froth for Heinemann. Title will remain the same – Pharaoh’s Daughter. Not Moses’ girl-friend, but a lady addicted to gaming.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 28 April 1941.

Learning to type

By May Georgette’s plans to start writing the new novel had been interrupted by one of the unexpected realities of war. For years, she had written her novels by hand and then sent the completed manuscript to a local typist. Once her manuscript was typed it would go to her publisher who would then return the proof pages to her for correction. Upon finalising the proofs she would send them back to the publisher to be prepared for printing. Once her latest book was ready for publication, Georgette would destroy her handwritten manuscript and start work on her next novel. This system had always worked well, but now the war had caused many typists to swap their usual employment for War work. Georgette tried to find a typist to handle Envious Casca for her, but was eventually compelled to report that

‘I have had hell on earth trying to find a typist able to deal with my book, & have been obliged to do it myself. No one in Brighton has ever heard of typing a novel in under a month, & I daren’t send it to town. It is a great bore, & such a waste of time, when I might be working on Pharaoh’s Daughter. I don’t quite know how long I’m going to be over it, but I hope not more than ten days

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 14 May 1941.

In the end, she did it in a week and, while it meant putting Pharaoh’s Daughter to one side for a time – which was frustrating – there was to be an unforseen benefit to typing up her own work. On 19 May 1941, she reported to Moore that she had not only typed 80,000 words in a week, but had also revised as she went. Georgette hadn’t particularly enjoyed doing it, but that was partly because she was itching to get on with the new novel!

I’ve got the most entrancing books out of the London Library, all about gamesters, for P’s daughter

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 19 May 941.

“The Muse is obstinate”

Over the next two months, other things interrupted Georgette’s attempts to write her new historical novel. One of these was an idea for a completely different kind of book which would eventually come to obsess her. But by mid July, she had put her distractions to one side and, determined to get on with Pharaoh’s Daughter, penned a long letter to Frere:

My dear Frere,

Such trouble as I have been having over that wretched girl, Faro’s Daughter! Or Pharaoh’s Daughter – which do you like? You needn’t bother to answer, if you’re busy: I shan’t pay any attention, anyway. And I haven’t unraveled it all yet, perhaps because there has been a Moon, which affects me strangely, so that I am not certain, and even my complexion shifts to strange effects – et seq. And perhaps because the Muse is just obstinate – you must, in your dealings with Inkies, have encountered this phenomenon before, and if you thought that this author was not dependent upon inspiration in all its more aggressive forms that is just where you are wrong …

Your razor-edged mind (copyright) has by this time leapt to the conclusion that all is not well with the child. Well, I wouldn’t go so far as to say that exactly. It’s just like you to go leaping to a lot of false conclusions: that’s what I always felt about you, Mr Frere: believing the worst, and goading me on to present MSS at idiotic times of the year, and then grumbling and cursing because they don’t turn up , and not listening to a word I say in my own defence, but going on interrupting like this, and reminding me that I said whatever you think I did say, which I couldn’t possibly have in any case, and very likely losing bits of it when you do get your impious hands on the rotten book, or even refusing to publish it out of sheer spite, which just shows that you can’t have any head for Business, because naturally it’s a very fine work, and immensely entertaining, absorbing, witty, scintillating and erudite. Well, what I mean is, it will be, when I get around to writing it. No, then, I haven’t started it, since you must know…

Elusive, that’s what it is. The plot, I mean. I see it up to a point – and damned silly, I mean damned good it is – but I don’t quite see what it’s all leading up to, or what to do with the ends, or why the hell I should make up such a lot of rot – make up such an ingenious story at all.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 16 July 1941.

A Hampton Court maze

Having ‘oiled her wrist’ so freely in the first half of her letter to Frere, Georgette then proceeded to write out for him an outline of her story insofar as she had worked it out. Her letter is not only a delightful summation of the story, but also a fascinating insight into just how much working out of her plot and characters Heyer had done in her head before she had written a single word!

Mr Ravenscar is a winner from the word go. I won’t hear a word against him, and if the schoolgirls don’t like his being tied up and dumped in the cellar they will just have to put up with it. I think myself that Miss Grantham took rather an extreme view of his delinquencies, particularly when you consider that she was in love with him at the time, but she’s so strongminded that it’s no use arguing the matter. And if more men – particularly publishers – were dumped in cellars – but I’m sure I’ve no wish to be offensive. Treat me right, and – I seem to have wandered. Where – oh, yes! Well, as I said, Mr Ravenscar (Max to his friends) is a winner, and no trouble at all. Nor I fancy shall I have much trouble with young Lord Mablethorpe. He seems too big a simp to bother anyone, and can be provided for nicely. Hence Phoebe Blandford. But what, I ask you, is the precise role of the Earl of Ormskirk? Yes, yes, of course he’s villainous: that’s obvious. But what does he do? Did he really want to marry Phoebe? It seems frightfully unlikely to me, and I would rule it out of court if it were not for the fact that someone objectionable wanted to marry her. Max? Yes, I admit that’s an idea, but there would be certain difficulties. Still, I’ll think about it. But if that were so, what do I do with Lord Ormskirk? It’s no use saying jettison him, because you don’t suppose, do you, that I’m going to abandon a lovely name like that? He’ll have to have Worse-than-Death designs on Miss Grantham, and buy up the bills, and mortgages and things. Then he can call her his Cyprian in public, and Mr Ravenscar, who’s been calling her a lot of much worse names, can knock him down, and then they can have a duel –guess who wins! And Max can buy the mortgages and things off Ormskirk, and –Gosh, yes! I’ve got it! Eureka! Must write up Mr Lucius Kennet, soldier of fortune to make him look like possible hero, so that Mr Ravenscar (outsize in cads: women love cads) can go on being objectionable, and use the mortgages and things not as deus ex machina, but as persecutor. No, no! Not, I think, improper designs on the poor girl: just to get her to relinquish young Mablethorpe, who is Max’s cousin, and starts off by being in love with Miss Grantham. I really can’t go into it all now, because it’s very complicated, Miss Grantham never having had the least intention of marrying Mablethorpe, and the whole imbroglio having arisen out of the idiotic way in which Max handled the situation.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 16 July 1941

By the time she had enlightened Frere about these various plot points and written to him as though he were actually sitting beside her, the book suddenly fell into place. Georgette thanked him for ‘listening’ and told him triumphantly that ‘I really think that’s done it. After weeks of fretting around in a sort of Hampton Court maze, too!’

Straight to the typewriter

Now that she knew who her characters were and had worked out her plot, Georgette was ready to start writing. With no typist in the offing, for the first time in her life, she decided to write her new novel – now called Faro’s Daughter – straight to the typewriter. This was no easy task for, as she told Moore, she only used three fingers and had to type single-spaced on account of the wartime paper shortage. But just three days after writing to Frere, Georgette was already well into chapter two and her hero, Max Ravenscar, had encountered the lovely Miss Deborah Grantham in her aunt’s gaming house and was ‘punting heavily at E.O.’ Faro’s Daughter is one of Georgette Heyer’s clever, witty novels. It sparkles, but it also has an edge. The sparring between the hero and heroine is intelligent, sardonic, emotional and, at times, brutally honest. There are misunderstandings galore but they are believable because they are so well crafted. As Jane Aiken Hodge observed:

Faro’s Daughter has one of her most elegantly worked out plots, with surprise piled on surprise at the end. Having read it once, at speed, the conoisseur will re-read it more slowly and enjoy noticing the delicate stages by which Deb and Ravenscar fall into love. He “began reluctantly to feel interested in the working of Miss Grantham’s mind,”‘ while Deb’s increasing rage with him is equally suggestive.

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Pan, 1985, p.65.

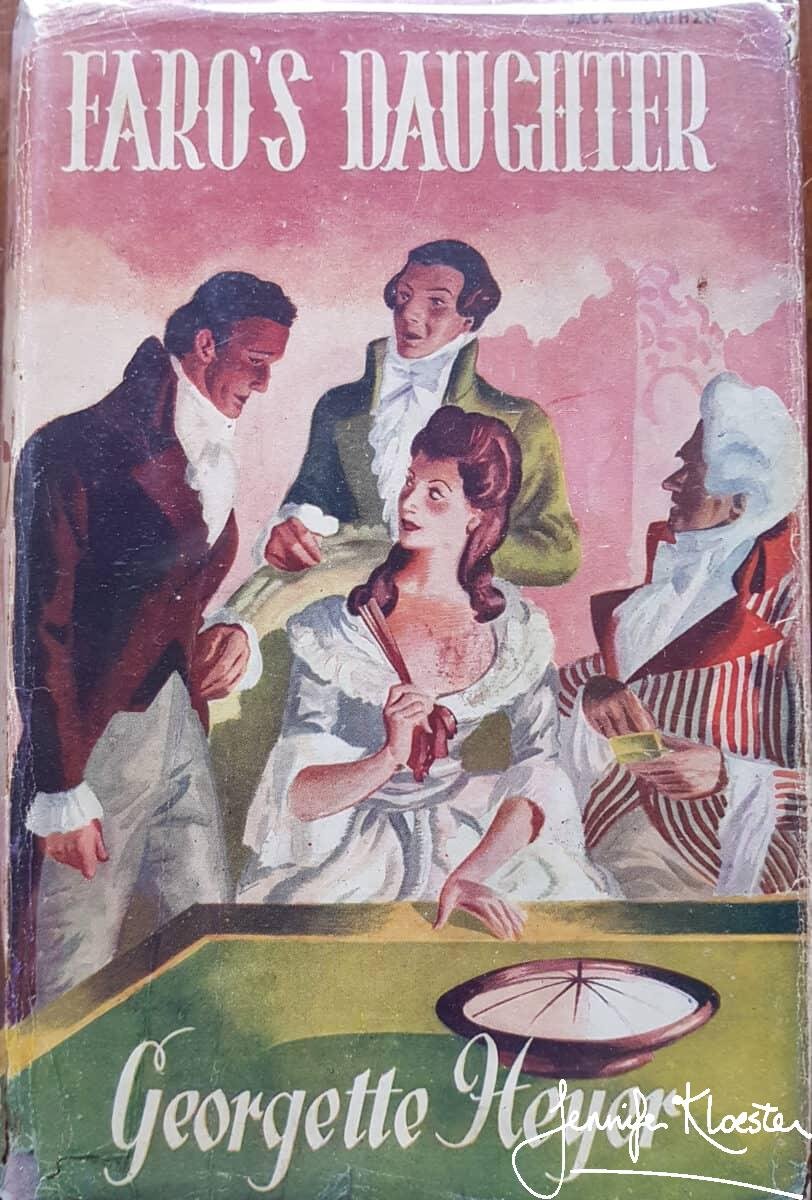

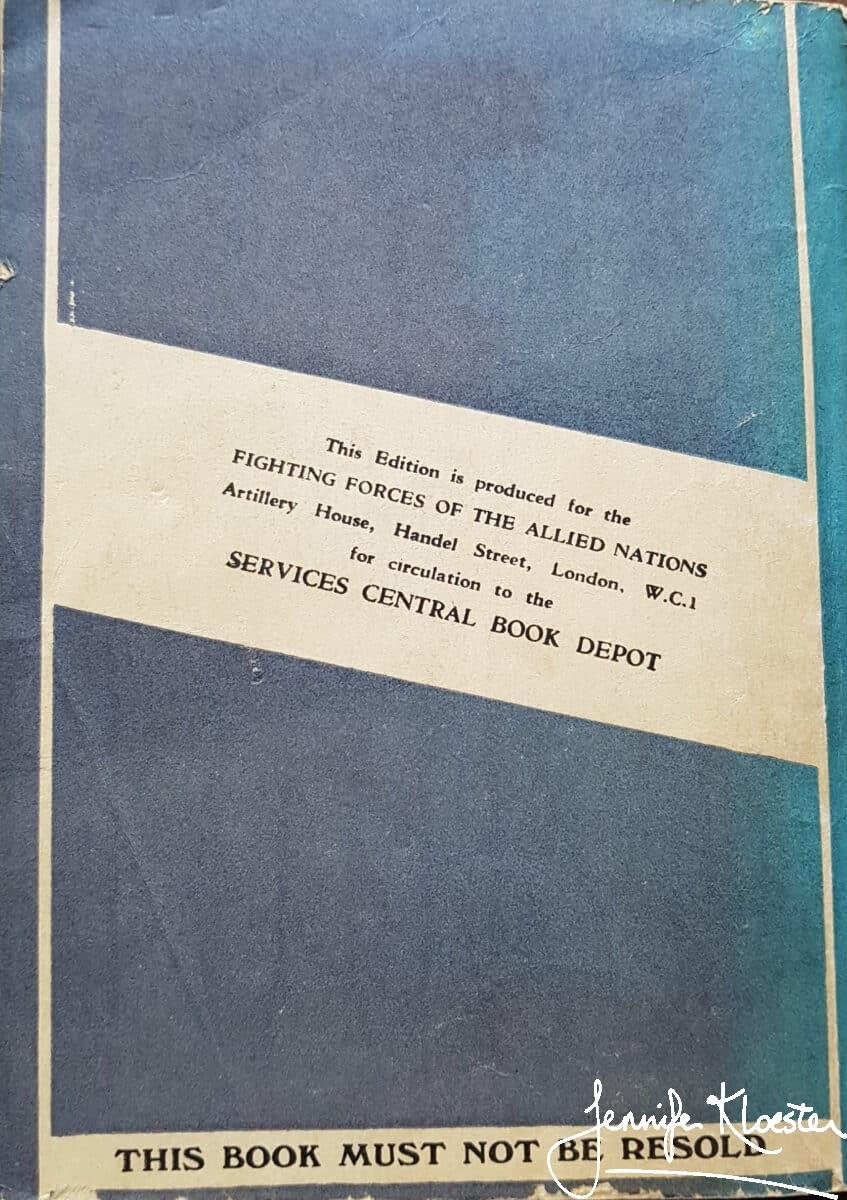

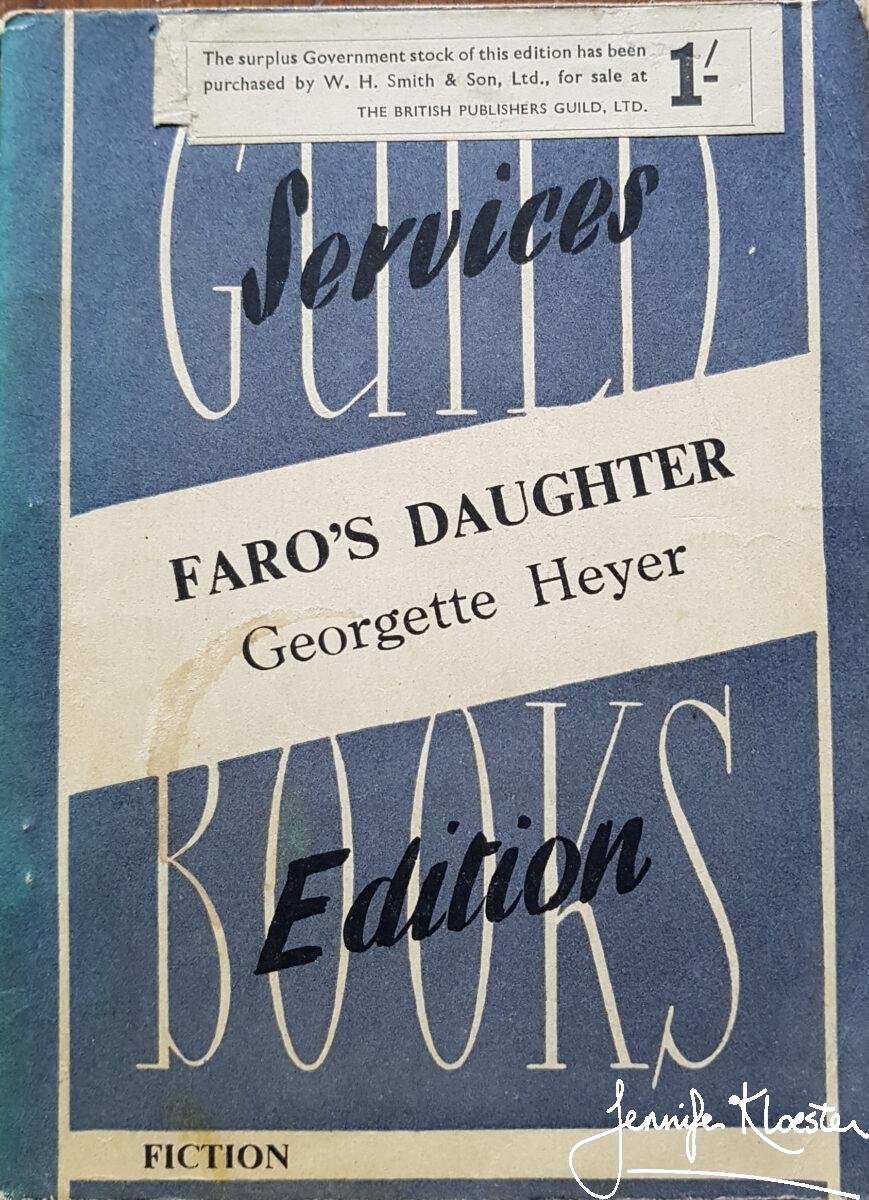

It seems incredible that Faro’s Daughter was written in less than a month! But, as Georgette herself reported, she typed it ‘straight from her head to the machine!’ On 19 July she had written a chapter and a half, by 25 July she had written the first 20,000 words, resisting every temptation to ‘pick up a pen, ana spare sheet of paper’ when reaching an ‘obstinate passage’. Although she made many mistakes in her typing and confessed that the manuscript ‘would probably make Heinemann’s pass out’ when they saw it because of the single-spacing and corrections, Georgette was proud of her progress. On 10 August 1941, twenty-two days after she had begun it, Georgette finished Faro’s Daughter! Typing it as it came out of her head, she had written 88,000 words in under four weeks! She was delighted and triumphantly told Moore how she had gone ‘on and on and on, with only one hitch, lasting for an hour, when I sat back, and wondered what was going to happen to the various persons assembled in the book.’ It is worth reading (or re-reading) Faro’s Daughter with this remarkable achievement in mind. There are not many authors who can write such an entertaining and enduring classic so quickly! (I wish I were one of them!) Despite its rapid creation Faro’s Daughter is a book to savour and enjoy; its author’s enjoyment in writing it permeates every page!

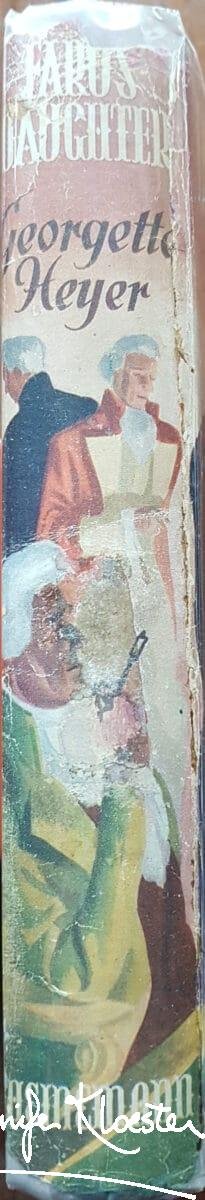

The 1967 Pan edtion

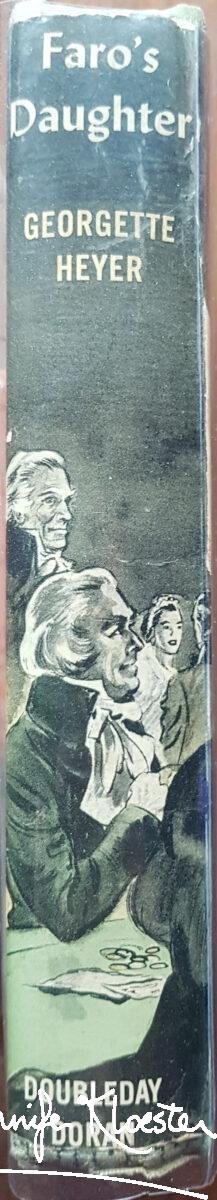

The 1971 Pan edition

2 thoughts on “Faro’s Daughter – written straight to the typewriter!”

Another of your excellent pieces for me to read when I am wondering what on earth to do! Of course, I do have things to do, but reading about Georgette Heyer from your own most excellent ‘pen’, always trumps anything else!

I know we talk about Heyer as a ‘genius’, but that much work, persistence end energy must surely be that of a really strong character as well. And writing during war time and all that entails for her, Ronald and young Richard… well, accomplishments indeed.

I live near Ish to Brighton (30 miles west along the coast) and know the place they moved to. I wonder if they had a good view over the sea to help her creative juices?

Thank you again Jennifer – I smiled all the way through reading Ms Heyer’s letters and imagining her as she wrote them. Best of wishes, Sharman

That’s so lovely of you Sharman. I like to think that she had a view of the sea. She certainly had one for her next novel, Penhallow. I hope you will enjoy that post which will be posted tomorrow. Thanks for commenting. Warm wishes, Jen