By August 1933 Georgette And Ronald had moved into their new home, Blackthorns, in Toat Hill near Slinfold, Sussex. The house was a large and comfortable one and the Rougiers had at least two servants to help with the domestic work and a nurse for Richard. He was a bright, exuberant child and his parents were proud of him, although in the typical English style of the time, they were not tactile parents and did not encourage overt displays of emotion. Georgette’s main outlet for her emotions was always her books and Blackthorns proved to be ideal for writing. It was very private and it had a large garden and woods in which to walk. Georgette always enjoyed gardens and often found respite in them from her busy writing life.

Georgette picking sweet peas in the garden at Blackthorns.

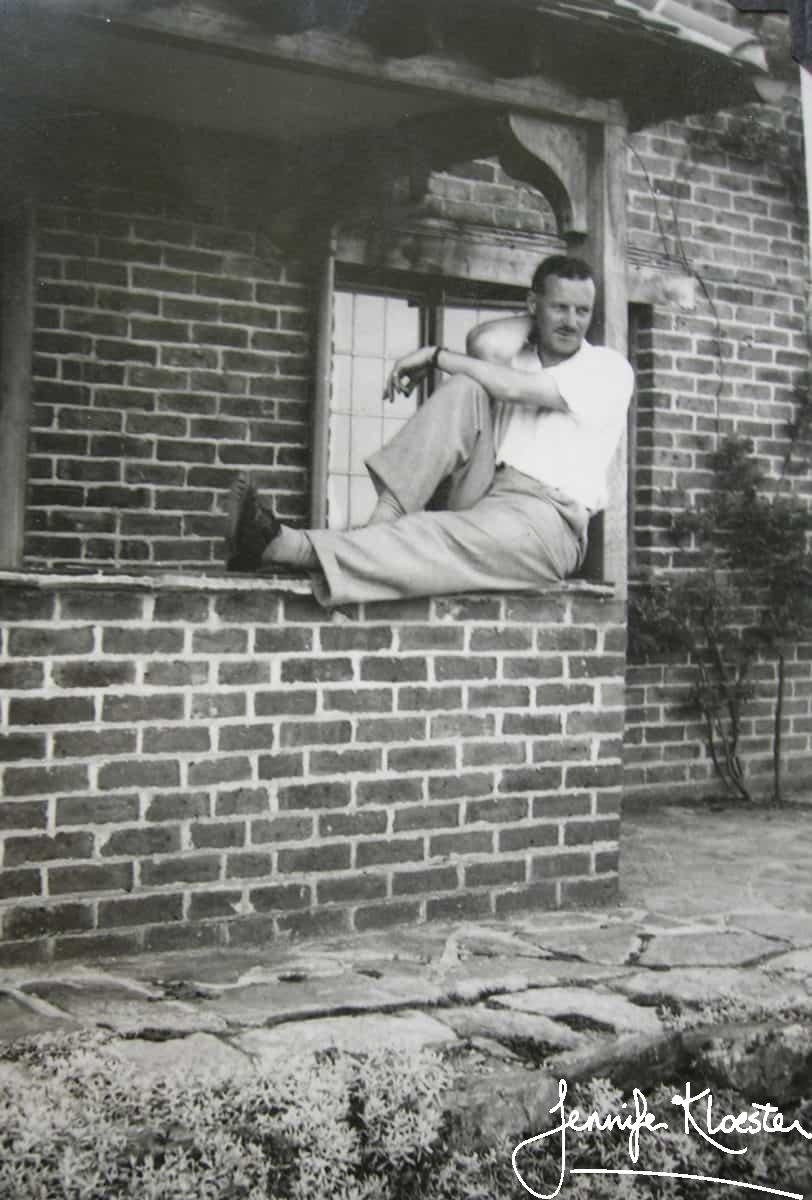

Ronald relaxing on the front porch at Blackthorns.

Georgette began writing her third detective novel soon after the move to Blackthorns. Originally called Murder on Monday, Longmans would publish the book in March 1934 as The Unfinished Clue. As with her previous detective-thriller, Why Shoot a Butler? the setting was an English country house and once again Georgette introduced a one-off detective. Inspector Harding is a charming policeman and a gentleman and, if she had not chosen to marry him off to the novel’s very intelligent heroine, Dinah, by the end of the novel, Georgette might well have made of him one the genre’s iconic detectives. Harding is an engaging young man who deals admirably with the novel’s difficult characters. These are many, beginning with the unpleasant and belligerent Sir Arthur Billington-Smith, his weak-willed, nervous wife, Faye, her strong-silent-type lover, Stephen Guest, Sir Arthur’s angry and rebellious son, Geoffrey, and, best of all, Geoffrey’s marvellous fiancée, Lola de Silva, a Mexican cabaret dancer who is utterly oblivious to the protocols and etiquette of an English country-house party! It is Lola who sets the house by the ears and Lola who inspired the great Dorothy L. Sayers to write of The Unfinished Clue:

‘I said last week that good writing would often carry a poor plot, and here is a case in point. Reduced to its main outlines The Unfinished Clue has the stamp of stereotype all over it. Here is the same old week-end party: the disagreeable rich man, who is stabbed in the study, the down-trodden wife, the rebellious son with the undesirable fiancée, the hard-up nephew, the wife’s lover, the husband’s petting-partner and her husband — all the stock characters, including the mysterious widow out of the victim’s past and the gentlemanly detective with the sugary love affair, together with a solution which had grown whiskers in the sixties [1860s!] and is as preposterous now as it was then. And yet, simply because it is written in a perfectly delightful light comedy vein, the book is pure joy from start to finish. Lola, the fiancée, by herself is worth the money, and, indeed, all the characters from the Chief Constable to the Head Parlourmaid, are people we know intimately and appreciatively, from the first words they utter. Miss Heyer has given us a sparkling conversation-piece, rich in chuckles, and all we ask of the plot is that it should keep us going until the comedy is played out.

Dorothy L. Sayers, The Sunday Times, 1 April 1934

The Unfinished Clue received several good reviews, but it would not appear in America until 1937, three years after its UK publication. By then Doubleday Doran had already published three of Georgette’s detective novels, changing the name of Death in the Stocks to Merely Murder for the benefit of those Americans unfamiliar with the sight of stocks on the village green and which would feature so prominently in that particular novel. An astute publisher, Doubleday designed a series of excellent dustjackets for half a dozen of Heyer’s mystery novels, including the “cast of characters” jacket for The Unfinished Clue in which four of the main characters each have their own logline to hook the reader. Her novel’s delayed sale to Doubleday and belated appearance in the USA may have been one of the reasons for Georgette’s growing dissatisfaction with Longmans’ handling of her books. In 1930, Georgette had been appalled by the publisher’s jacket design for her final contemporary novel, Barren Corn, and unimpressed by the firm’s head, Willie Longman, whom she once described as ‘vapid’. In March 1934, shortly after the publication of The Unfinished Clue, Georgette met her agent, Leonard Moore, at her club to discuss her future with Longmans.

Here’s an elegant buy in smart, streamlined bafflement by the author of Merely Murder [Death in the Stocks], Why Shoot a Butler?, and Behold, Here’s Poison. Clever gabble, malicious characterization. fool-proof plot and high excitement are among the treats.

Will Cuppy, describing The Unfinished Clue in his article “Mystery and Adventure”, New York Herald Tribune Books, 21 February 1937

Although she was not really a ‘club’ sort of person, early in the 1930s Georgette had joined the Empress Club in Dover Street in central London. Established in 1897 as a club for women, its subscribers were a mix of upper-class, educated and professional females. Purpose-built and well-designed, the club

‘boasted two drawing rooms, a dining room, a lounge, a smoking gallery and a smoking room, a library, a writing room, a tape machine for news, a telephone, a room in which servants could be interviewed, dressing rooms, and one of the best orchestras in London.’

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928, Routledge, New York, 2001, p.120.

- The Empress Club was an elegant and sophisticated environment which entirely suited Georgette and enabled her to play host to her agent or friends at lunch when she visited the capital. She and Moore met there late in March 1934 to discuss her books. Georgette had begun a new book about which she was very enthusiastic, but she also wanted to complain to him about Longmans. She was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the firm’s handling of her detective novels and had been less than impressed when, after sending back the page proofs of The Unfinished Clue, she had received ‘frantic and numerous telephone messages desiring me to inform them where are the proofs?’ This sort of inefficiency was something she loathed and enough to make her think of leaving the firm. Over the years and as evidenced in her many letters, once Georgette’s displeasure or disapproval was incurred it generally marked the beginning of the end. She was very protective of her books and of her creative life and could be very stubborn where they were concerned. It usually took her a long time to change direction or make a decision to change a long-standing arrangement, but once she had made up her mind the decision was nearly always irrevocable.

It was an easy commute from Blackthorns to London as, in the 1930s, Horsham had its own station on the Guildford branch of the Southern railways. Georgette visited London to shop, lunch at her club or meet her agent who, before the Second World War, had an office in the city. She had a busy life and her writing took up a great deal of her time. During her research for the Private World of Georgette Heyer, Jane Aiken Hodge spoke to locals who remembered Georgette, in particular:

‘The old lady who lived at the end of the drive remembers Richard as a lonely little boy who would come and see her and tell her that Mummy was busy writing. His father would drop in and pick him up on his way home from work. His grandmother, Mrs Heyer, had moved to Horsham and she, too, was apt to complain that her daughter was always busy.

Jane Aiken Hodge, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, Pan, p.45

It must have been hard for Georgette being the main family breadwinner, attending to Richard and to her mother whenever she could, keeping the house running smoothly, and writing two books a year as she would throughout the 1930s (she published only one book in 1931 and 1939). Georgette’s creative powers were remarkable but she did pay a price for her productivity, an experience with which many male writers of her era were far less familiar. In these modern times, it is easy to be critical of her apparent neglect of Richard but for a woman of her class it was not so unusual to have one’s child attended to by a nurse or a nanny. Georgette loved Richard and he always knew that although there were times when he longed for a closer emotional tie with his mother. The Unfinished Clue was the next step in Georgette’s evolution into a writer with a growing reputation for writing detective stories that were not only clever, but also witty. She had a penchant for writing characters with a propensity for making jokes about the corpse and doing their best to infuriate the police. This would bear fine fruit in her very next book, Death in the Stocks.