“Something far more Amazing”

Georgette Heyer was pregnant when she wrote to her agent in September 1931 to tell him that she ‘had something far more Amazing up my sleeve. What price a sequel to These Old Shades?’ The letter was a buoyant one full of enthusiasm and written with an energy that reflected her ‘insane rapture’ over the expected ‘addition to the family in February’. Georgette had a very happy and untroubled pregnancy and from the beginning was convinced that the baby would be a boy. It may have been this conviction and her ensuing thoughts about what having a son might be like that inspired her to write the story of the son of two of her best-loved characters: Justin Alastair, Duke of Avon, and his spirited wife, Léonie. They had become favourite characters with her growing audience and six years after its publication These Old Shades had already enjoyed fourteen reprints. The success of the first book coupled with her need for money inspired Georgette’s idea for the sequel and she happily told Moore that:

… It is a return to this author’s popular manner, & – discarding hyperbole – is a sort of “Twenty Years After”, for it is to be about Avon and Léonie’s son, Dominic. He is going to be quite remarkably like his father, with a bit of Ma’s hot temper thrown in, & her total disregard for human life. I haven’t thought out the whole plot, yet, but he’s to be a Bad Man (but Terribly Handsome and Attractive, of course) & he’s to be a Famous shot. One of those impossible people who shoot as well Drunk as Sober. There will of course be an Abduction, a villain (neither handsome nor Attractive), a cross-country Chase, hair-breadth escapes, etc. And I propose to give Léonie, Avon, Lord Rupert, & Co. good fruity parts in the epic.’

Georgette Heyer, letter to L.P. Moore, 4 September 1931.

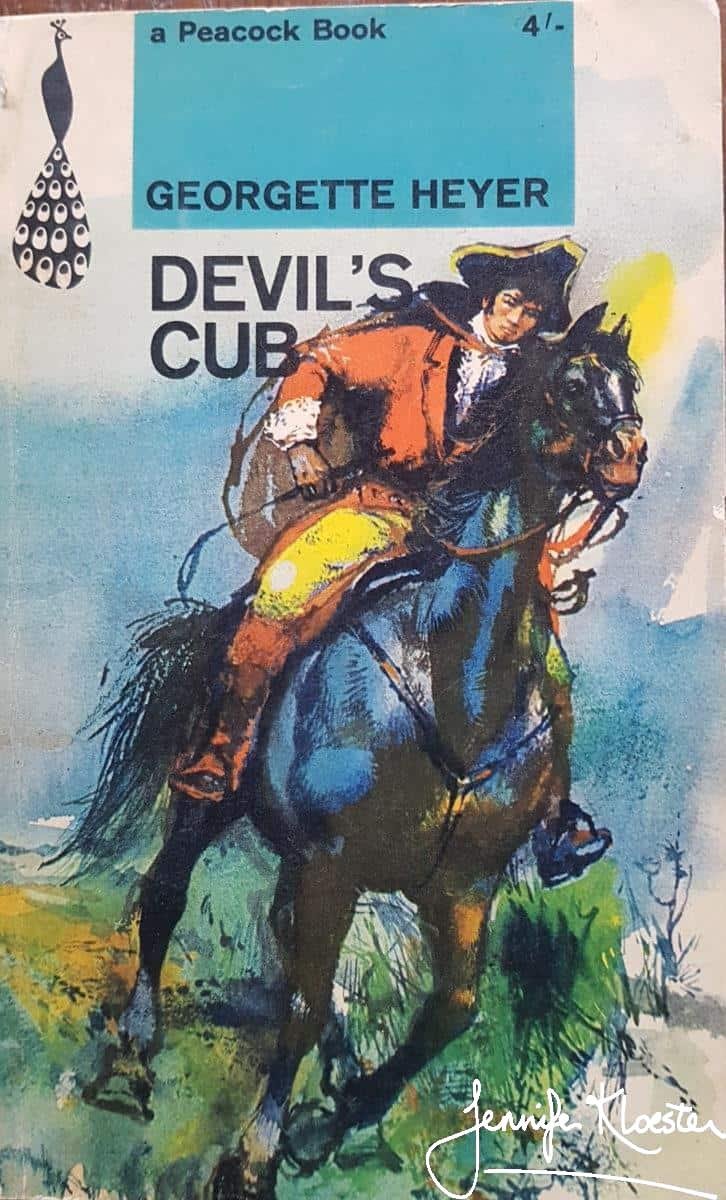

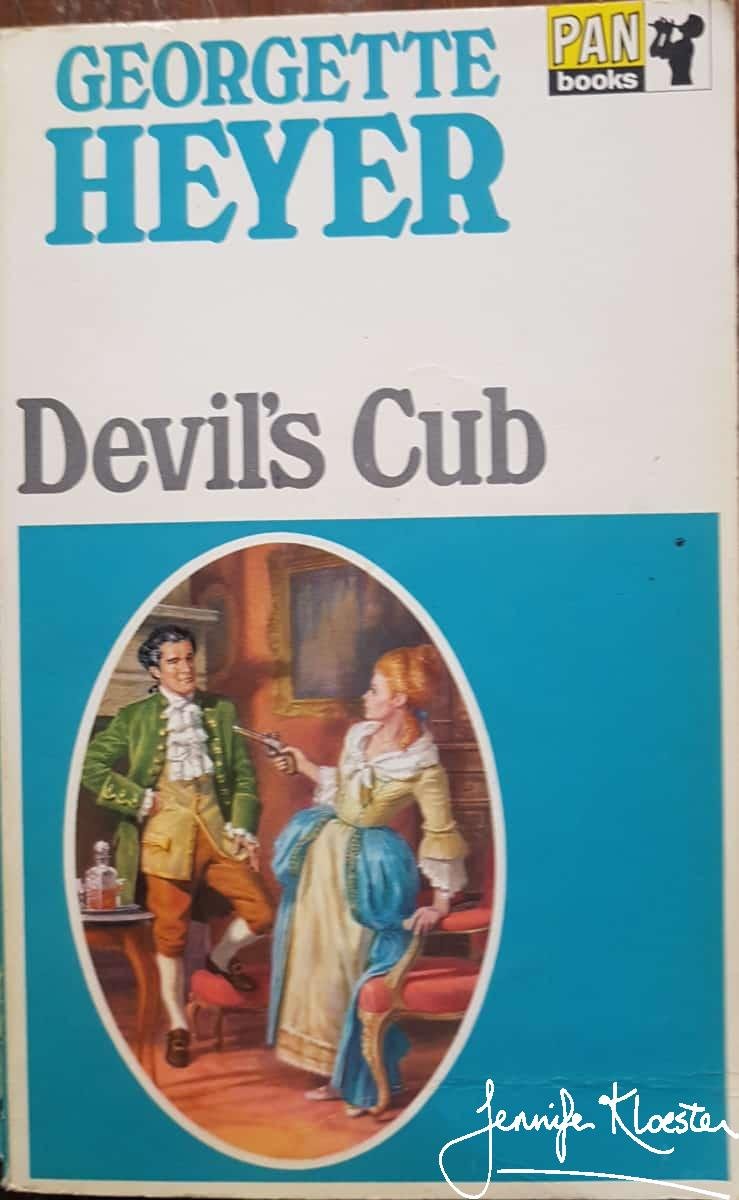

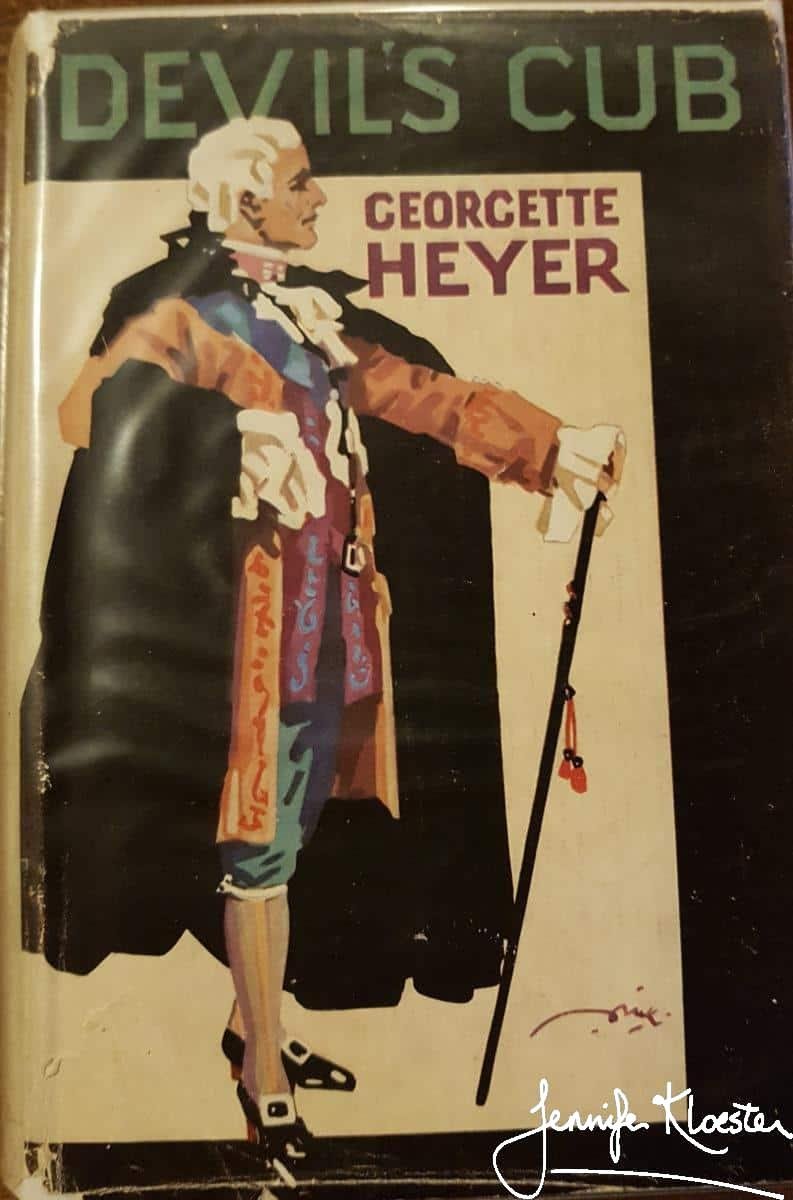

Devil’s Cub and Heyer’s first anti-heroine

The new book was Devil’s Cub and in it Heyer gave full rein to her love of humour, adventure and of inverting several of the romantic conventions. As one reviewer said, her ‘excellent, easy style developed early’ and she used it to great effect in this page-turning story. It features one of her most attractive heroes in Dominic Alastair, Marquis of Vidal, as well as her first anti-heroine in Mary Challoner. Mary is an intelligent, quiet, strong-minded female with neither beauty nor fortune to recommend her. Unlike Georgette’s earlier heroines, she has never had an adventure but lives quietly at home with her pushy mother and crudely ambitious, beautiful younger sister, Sophia. It is Mary’s attempt to save Sophia from becoming Vidal’s mistress that sees her ruthlessly abducted and carried off to France. The theme of abduction, threat of rape, submission and the victim’s inevitable falling in love with her captor was a common one and especially well-known to readers of bestselling author Ethel M. Dell’s overly dramatic but hugely popular novels. Georgette had read Dell in teens and drawn inspiration from at least one of her stories – though not in the way one might think. Whereas Dell adhered to and enlarged upon the tropes of male domination and female submission in Devil’s Cub (as Barbara Bywaters explains) Heyer ‘twists features of the romance plot to expose the myths behind the story’ and takes great delight in turning readers’ romantic expectations on their heads; instead of the classic scene where the macho hero arrives to ravish his captive and she – a helpless female – eventually succumbs to the passionate heat of his kisses, Heyer’s Dominic finds his ruthless intentions thwarted:

“And now,” said Vidal silkily, “and now, Miss Mary Challoner…!”

Miss Challoner made a heroic effort, and raised herself on her elbow. “Sir,” she said, self-possessed to the last, “I do not care whether you go or stay, but I desire to warn you that I am about to be extremely unwell.” She pressed her handkerchief to her mouth, and said through it in muffled accents: “Immediately!”

His laugh sounded heartless, she thought. “Egad, I never thought of that,” he said. “Take this, my girl.”

She opened her eyes once more, and found that his lordship was holding a basin towards her. She found nothing at all incongruous in the sight. “Thank you!” gasped Miss Challoner, with real gratitude.

Georgette Heyer, Devil’s Cub, 1932

Heyer loves to make us laugh and such is her skill that in just two sentences she makes the reader aware of Mary’s intelligence and of her calm, rational approach to flattery:

‘in my eyes,’ declared Joshua, ‘you are the prettier.’

Miss Challoner seemed to consider this. ‘Yes?’ she said interestedly. ‘But then, you chose puce.’

Georgette Heyer, Devil’s Cub,

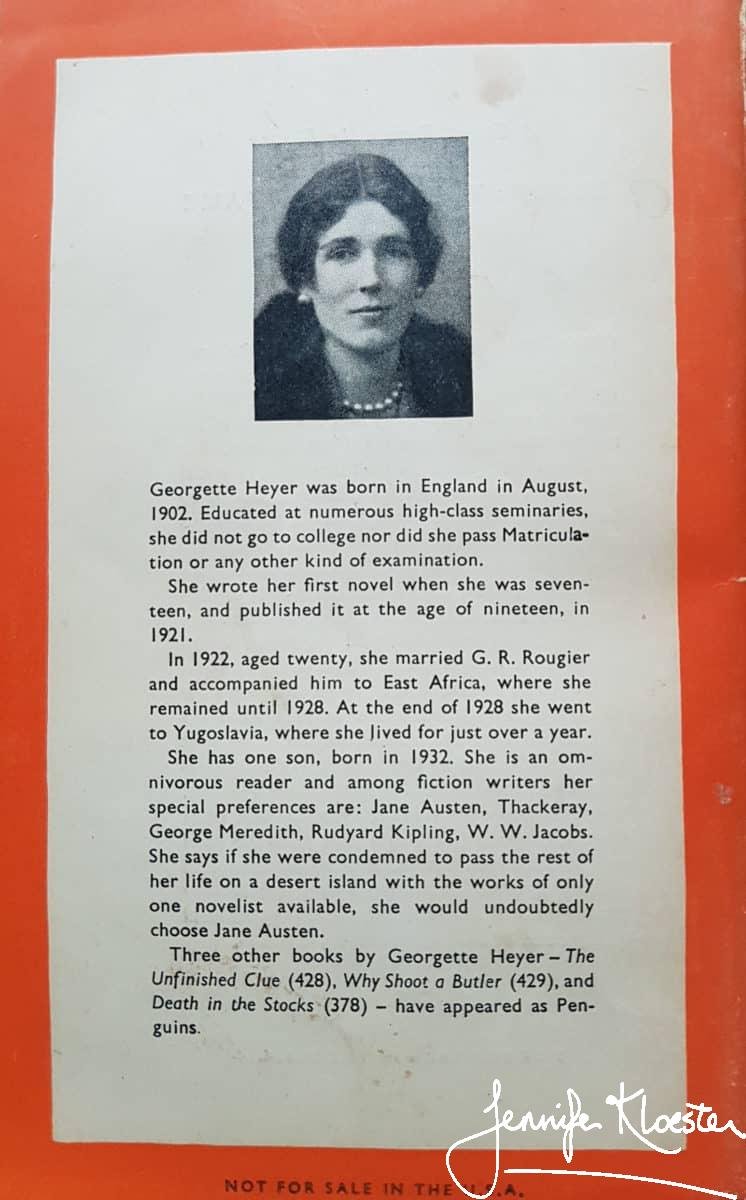

The 1953 Penguin edition

Georgette Heyer’s bio (with errors) on the back of the Penguin edition

Mary takes charge

From that moment on, Mary repeatedly takes charge of the wilful man with whom she has long been in love. She is rational where he is hotheaded and impulsive; she is calm and self-assured, while he is erratic and (in the presence of his father) nervous and uncertain; she is determined to resist him (and is mostly successful), just as he is determined to win her. Throughout Devil’s Cub – as in all of Heyer’s novels – both protagonists learn and change in attitude and understanding. This is the genius of Heyer: her characters live and even her most dramatic novels are replete with wit and humour. And, for all they are romantic, they are also infused with a remarkable dose of very unromantic, practical insight. It is one of the reasons why her books make her readers laugh aloud – for Heyer delights in turning things on their head. She is, as Carmen Callil wrote of her, ‘a subversive Sybil’ and one who ‘used their power and influence to change the way women view themselves’. Mary Challoner was one of the first among Heyer’s many memorable heroines to achieve this.

No conscious message

Heyer, of course, had no conscious message to push. She was not an avowed feminist, although she clearly believed in a woman’s right to work and to use her creative powers and she believed strongly in her own ability to write excellent books. She was not, however, above poking fun at herself or her work as this tongue-in-cheek passage about her new novel reveals:

If Heinemann advertized after the manner of the talkies they would puff the tale I meditate after this manner:- “Read this dynamic story of love in the 18th century!! You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll thrill!!! Don’t miss it!!!! It is a story of how a wicked young rake found love after hair-raising adventures, & poignant heart-searchings!!!!! You will adore Dominic Alastair and his beautiful bride, Helen!!!!!! A Romantic Yell! The finest thing published for years!! Laughs on every page!!! A riot of Fun!!!! An all-talking, all-laughing, all-fighting Furore!!!!! The Book the World has been Waiting For!!!!!!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 4 September 1931.

(I love her use of exclamation marks – she begins with one, then two, three, four, five, six, before she does it all over again.. Georgette loved exclamation marks and used them to good purpose in her chatty stream-of-consciousness letters.)

Attitudes to class

Another aspect of Devil’s Cub that reflects Heyer’s attitudes was her ideas about class. Georgette was very much a product of her time. Raised by Victorian parents and born into an Edwardian world she imbibed the idea of a social hierarchy via osmosis, personal experience and books. The idea that ‘breeding will always tell’ and ‘class will out’ was a common one in early twentieth-century England and what may seem abhorrent to us today, was largely unquestioned in the world in which Georgette Heyer lived and wrote. It was due to her unquestioning belief in class that in Devil’s Cub it was important that Mary be a ‘suitable’ bride for her Marquis. Though Mary’s deceased father was well-born, her mother’s vulgarity and middle-class origins made marriage to a Marquis unlikely – if not impossible. It is only the existence of a well-bred, paternal grandfather in General Sir Giles Challoner (who is also a friend of VIdal’s father) that makes Mary an acceptable wife. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the upper classes placed enormous emphasis on birth and breeding and such attitudes were still prevalent throughout Georgette’s lifetime. She knew only too well, both historically and in her own time, that unless there was a fortune to be gained, for the most part the aristocracy only married where there was an acceptable lineage or family connection. This rule of acceptable birth was one to which Heyer adhered throughout her writing life. Jane Aiken Hodge described her as creating a ‘private world, with its private rules, and birth is important’; it is an apt summation, but she was also reflecting the historical reality – however snobbish and abhorrent it may seem to twenty-first century readers.

“Wolf of Avon”?

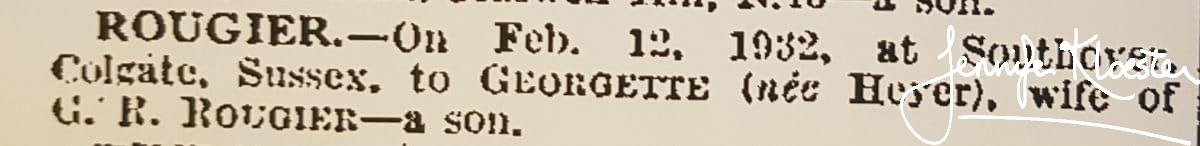

It took Georgette a little while to decide on the ideal title for the new book and she told Moore of several semi-humorous ideas for it, including The Son of the Duke, Wolf of Avon and an ironic suggestion from her brother Boris, who suggested calling it These Old Shadows. In the end she chose Devil’s Cub as one which would appeal to readers generally while conveying to those in the know that this was a book about the son of ‘Satanas’, her much-loved hero, the Duke of Avon. Heyer originally planned to finish the book in time for spring publication but did not complete it as hoped and so Devil’s Cub did not appear until November 1932. The delay in publication was hardly surprising, for in February she became a mother. Richard George Rougier was born at 3.40 on 12 February 1932 weighing eight pounds. Georgette and Ronald proudly announced his arrival in The Times and she soon learned to adjust her writing life around his needs, often sitting up all night to write. Two months after his birth on 21 April 1932, Richard was christened by the Reverend Arthur Maister at the local parish church of Colgate St Saviour. Several of Ronald’s and Georgette’s friends and family attended the service and Joanna Cannan (Pullein-Thompson), Dr Charles E. Harris: ‘the child-specialist’, and Boris were each named as godparents.

Baby Richard’s baptismal certificate, carefully filled out by his proud mama using two different coloured pens.

Richard, aged about six months.

Devil’s Cub gave Georgette new scope for her growing skill as a humorous writer. It was a genuine sequel to These Old Shades and she took great delight in bringing back Leonie, Rupert, Fanny and Justin Alastair for her readers’ enjoyment and wrote a clever comic dénouement that continues to give fans of the first book enormous satisfaction. Devil’s Cub was also the first of her historical novels to feature one of her serious young men in the character of Frederick Comyn whose ‘prosaic bearing’ and extreme propriety masks his penchant for romance; yet another example of Heyer’s skill in inverting the romantic tropes. It is not surprising to discover that nearly ninety years later Devil’s Cub, remains a firm favourite among fans and its bad-boy hero, Dominic, the Marquis of Vidal, one of their most adored men in all of Heyerdom.

In these two books Miss Heyer comes her nearest to playing with her readers’ sexual fantasies. She is so successful because she avoids coming very near … In Devil’s Cub Miss Heyer uses one of the stocks-in-trade of the romantic novel: the characters are in close proximity and without a chaperone almost from the beginning. This provides a sense of danger and drama and heightened expectation–the declarations of love, and the bedding, are of course delayed by the points of honour and twists of the plot until the end.’

A.S. Byatt, “Georgette Heyer is a Better Novelist Than You Think”, Nova, August 1969.