Already written

It was fortunate for Georgette Heyer that what would become her sixth published novel was mostly written when, on 16 June 1925, her father died from a massive heart attack. Only the day before she had signed her first contract with Heinemann for Simon the Coldheart – already published in the USA – and for a second, unnamed book. Struggling with the devastating loss of her adored father, friend and mentor, but determined to fulfil her contract, Georgette tried to write. Five months later In November she told her agent: ‘I haven’t yet started another book but I’m trying to. I think it will be modern.’ But, despite her good intentions, the ‘modern’ novel would not appear for another two-and-a-half years.

A ‘sequel’

It may have been desperation that caused Heyer to return to the manuscript she had begun three years previously in 1922. In January 1923 the book was almost finished and she had written gleefully to her agent, L.P. Moore, to tell him about this planned ‘sequel’ to her first novel, The Black Moth.

Dear Mr Moore

Here is the Black Moth – a very juvenile effort. I do hope you’ll like it! At the risk of earning a dubious headshake from you, I will tell you that sometime ago I began a sequel to it, which one day I shall wish to publish … It isn’t finished yet, but it will be one day. I’d like to make a success, then to get the Moth out of Constable’s hands and to induce another publisher to reprint in a cheaper edition, and lastly to bring out the sequel!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 23 January 1923, University of Tulsa Archive

‘Designed to catch the public’s taste’

It was a very clear plan and required only that Georgette ‘make a success’ before putting the finishing touches to her unnamed manuscript. She knew exactly what the story was about and was confident that she understood what readers wanted and how to please them. With rare youthful candour and an exuberance that would diminish after her father’s death, she told Moore:

‘The sequel is naturally a much better book than the Moth itself, and is designed to catch the public’s taste. I have also tried to arrange it so that anyone who reads it need not first read the Moth. It deals with my priceless villain, and ends awfully happily. Tracy becomes quite a decent person, and marries a girl about half his age! I’ve packed it full of incident and adventure, and have made my heroine masquerade as a boy for the first few chapters. This, I find, always attracts people!

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 23 January 1923, University of Tulsa Archive

Masquerade!

Georgette was familiar with many books and plays in which young women disguise themselves in male attire and thereby throw off the restraints and restrictions of their gender. Several of the Shakespearean plays – which Georgette knew and loved – featured heroines masquerading as men and the character of Britomart in Spenser’s Faerie Queen dons armour and has adventures in her male disguise. Georgette was also familiar with modern writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Berta Ruck, and Ethel M. Dell who also used the masquerade device.

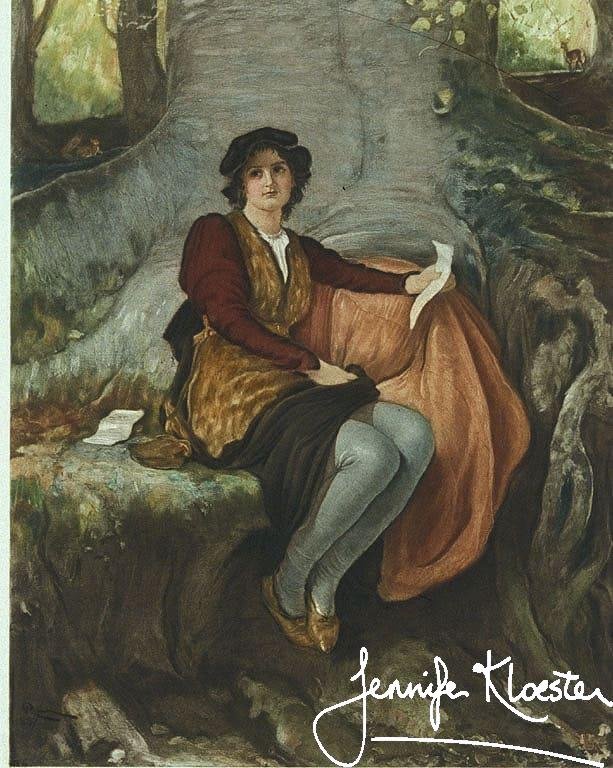

Fair Rosalind (1888) by Robert Walker Macbeth (1848-1910)

Portia by Henry Woods (English, 1846-1921])

Shakespeare Illustrated Public Domain

Struggling to write

But, despite her early enthusiasm, her father’s death stopped Heyer in her writing tracks and by November 1925 she had written nothing new. That month she told her agent, ‘I don’t think I have the heart to write a period novel.’ But Georgette had a contract to fulfil and, throughout her life, only serious illness would prevent her from meeting her contractual obligations. With no new book to offer Heinemann, she retrieved her unfinished manuscript and set about preparing it for publication.

‘I will try once more…’

Georgette returned to the unfinished sequel to The Black Moth and slowly began writing again. She later described the experience of returning to an unfinished manuscript in her most autobiographical novel, Helen. At the very end of the book, her heroine, the eponymous Helen, returns to her unfinished novel months after her father, Jim Marchant’s, sudden death. For those who know Heyer’s own story, these paragraphs from Helen are a poignant reminder of what she had lost and her struggle to return to the writing she loved:

‘She unearthed the manuscript from the bottom of her trunk, and sat down to read it. It was very hard to do this; Marchant’s pencilled corrections occurred again and again; and again: more acutely than ever did she feel the need of him; she had to force herself to continue.’ But at the end she said:– “I must re-write a lot of this. I know more than I did when I wrote it. I think quite differently.” …

She had set herself this difficult task; she persevered with it, and conquered at last her shrinking, her spells of hopeless depression, and the unreadiness of a pen so long laid by. At first there seemed to be no purpose in the writing fof this book, since Marchant would never read it; a score of times she was on the point of relinquishing the attempt to write, but each time she thought:– “I will try once more,”‘ until gradually the old facility came back, and a little of the old joy of writing. It was a different pleasure she had in it now, lacking the exuberance she had felt before, but she was relieved to find that there was still pleasure in her work.’

The book was finished at last, and sent to the typist. The spring came back into Helen’s step, and the light into her eyes. “There are still things to do,” she said.

Helen, Georgette Heyer, Longmans, 1925, p.325.

Like Helen in her novel, Georgette completed her manuscript and sent it to Heinemann. They published These Old Shades on 21 October 1926 with a first printing of 4500 copies. From the very first These Old Shades sold well, with a second printing of 4500 in March 1927 and another 4500 just eight weeks later in May. In its first ten years, These Old Shades would be reprinted almost thirty times. It was a phenomenal result for its twenty-five year-old author.