Home from Africa

In April 1928 Georgette and Ronald returned home from Tanganyika. After eighteen months in East Africa prospecting for tin, Ronald still had not ‘struck it rich’ and had decided to try his luck elsewhere. After a brief holiday in Uganda, the Rougiers sailed home from Mombasa, stopping along the way at Dar-es-Salaam, Zanzibar and South Africa, before arriving back in England in early April,. The week before they arrived home, Georgette’s second contemporary novel, Helen, had appeared in the bookshops with a long review in the Times Literary Supplement which concluded with the gratifying statement that, ‘this is a story which contains some good work.’ Georgette had by now moved on from Hutchinson’s and it was Longmans who published Helen. They would publish three of Heyer’s modern novels as well as her earliest detective fiction. Returning from Africa, Georgette set to work on a new book, Pastel her second modern novel for Longmans and which would contain much that was familiar to her.

But not for long…

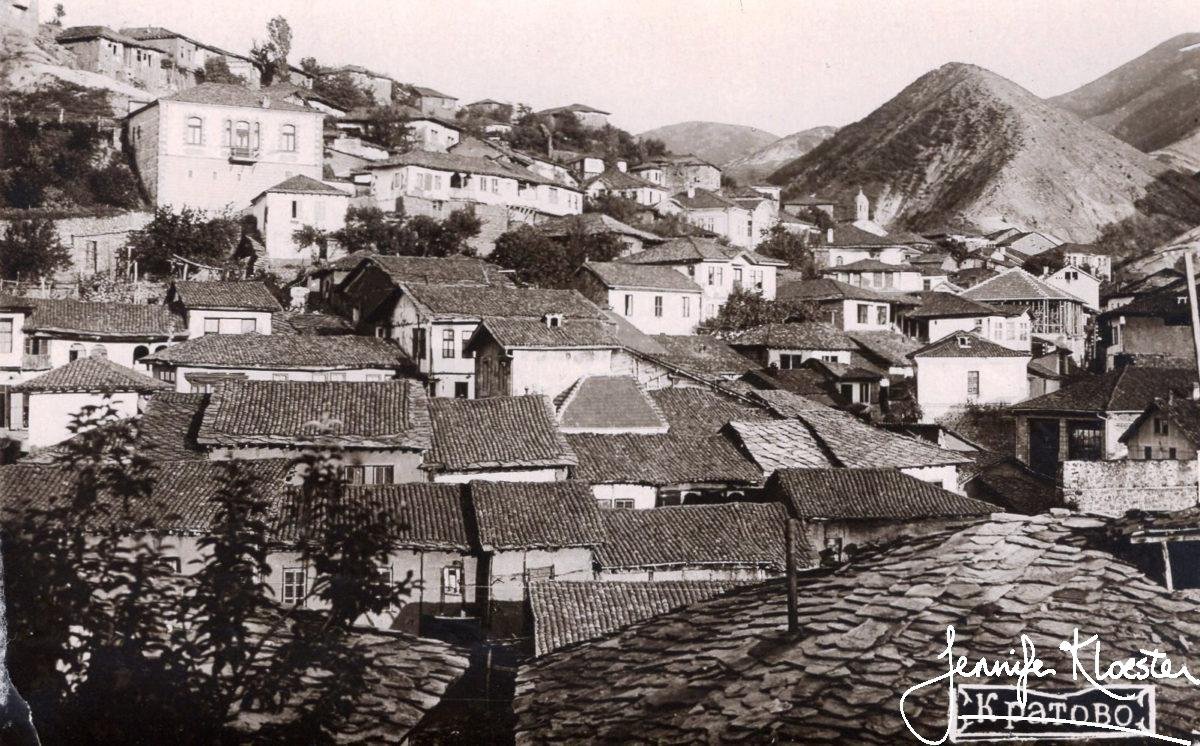

Once back in England, the Rougiers returned to London where Georgette’s mother was living in rented rooms at 44 Stanhope Gardens in South Kensington. It is not known if they lived with her or whether they found their own place to rent. Wherever they settled, however, it was not for long. Ronald was eager to obtain another overseas posting and that summer he found a job in Macedonia working for the Kratovo Venture Selection Trust Ltd. By August he had left London and made his way to the Macedonian capital, Skopje. From there he travelled by bus or car to their new home in Kratovo, a small village about an hour’s bus ride east of Skopje. As its name indicates, Kratovo lay inside the burnt-out crater of an ancient volcano. It was a small village but the surrounding area had been mined for its precious metals since Roman times. Ronald’s job would take him into the lead mines near the Bulgarian border where Georgette would later report seeing the names of slaves been carved into the rock centuries earlier.

44 Stanhope Gardens, South Kensington, where Georgette’s mother, Sylvia Heyer, was living when they returned from East Africa in 1928.

The medieval town of Kratovo where Georgette Heyer lived from 1928 to 1930. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kratovo,_North_Macedonia

Two books a year!

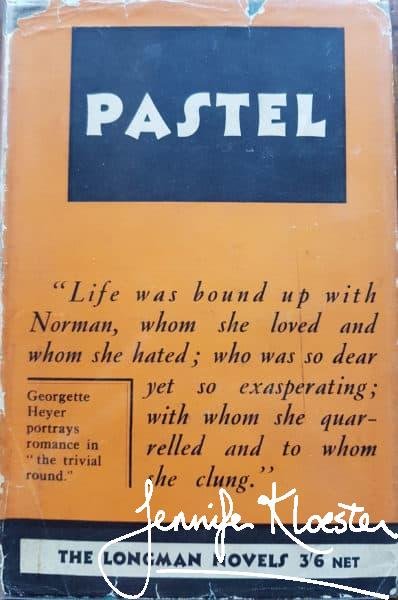

Perhaps because she was busy working on Pastel , Georgette did not travel out to Macedonia with Ronald that August but instead joined him there later in the year. She may also have wished to be in England for the release of her second novel, The Masqueraders, which came out in early September. It was a remarkable achievement to have two books out in a single year, but 1928 would mark the beginning of a a prolific period for Georgette Heyer. In the fourteen years between 1928 and 1941, she would write twenty-four novels with a average of two a year for all but three years (1931, 1933, 1939). Her publishers must have loved her! Heyer was unusual in having two different publishers for her work but the arrangement seemed to suit her with Heinemann publishing her historical fiction and, Longmans publishing her contemporary and detective fiction. For over a decade, Georgette alternated between writing historical novels and her modern or detective novels and it is a mark of her extraordinary skill that she was very successful in all three genres.

Published by Longmans in April 1928

Published by Heinemann in August 1928

‘Here is a book for Mummy’

In her previous contemporary novel, Helen, Georgette had created a fictional life-story for her heroine that at times drew on her own life and experiences to the extent that her brother, Frank Heyer, always said that Helen was her ‘most autobiographical book’. In Pastel Heyer would again draw on her experiences, though it is impossible to know just how much. A very telling and somewhat startling aspect of Pastel is revealed in the personal dedication which Georgette wrote in the front of her mother’s presentation copy:

‘Here is a book for Mummy, which is sent with love and the hope that She will like it. Some of it she may disagree with; some of it is designed to make her laugh; but whether she laughs or whether she frowns, this book should, on the whole, please her since it contains so much that is Really and Truly her – Dordette – Kratovo, April 1929’

Georgette also formally dedicated to her mother and it is tantalising, though not always easy, to try to discern Sylvia Heyer within the pages of the book. Pastel is the story of two sisters, Frances and Evelyn Stornaway, who live with their parents in quiet, suburban, middle-class “Meldon” – a thinly disguised version of Wimbledon where Heyer grew up. Frances is the elder of the two and a sensible, reliable young woman who ‘could look almost beautiful’. She is often in the background, however, because Evelyn is so vivid and vibrant and always the centre of attention. The two sisters actually look a lot alike, but Frances is the ‘pastel’ version of her sister – ‘a pale edition of Evelyn’ is how Heyer describes her. At a weekend house party, to which Evelyn is not invited, Frances meets Oliver Fayre and falls in love with him. He is the handsome romantic ‘hero of Asgard’ of her dreams, but when he meets her sister Evelyn it is love at first sight. No one but her mother ever suspects Frances’s passion and at every turn Mrs Stornaway fails to comfort her lovelorn daughter. Though she loves her mother, Frances struggles to find solace in Mrs Stornaway’s prosaic, practical advice that it is often ‘the dull things [that] turn out to be the most satisfactory’ nor is she helped by knowing that her mother hasn’t ‘much faith in the lasting qualities of a grand passion’. Neither statement gives Frances comfort as she struggles to suppress her envy when Evelyn wins Oliver’s heart and hand. Like Sylvia Heyer, Mrs Stornaway is Victorian, conservative, and unable to perceive her daughter’s deeper emotions. She wants Frances to marry Norman Acre, ‘who was such a dear boy and whom they had known for so many years’ and when Frances finally manages to confess something of her feelings for Oliver her mother tells her:

You know, dear, it isn’t always the first man you fall in love with who turns out to be the right one.’

‘And if Oliver wants Evelyn, don’t feel bitter about it. I like him very much, and I know just how his type attracts you. But he isn’t the sort of man I would choose for you, darling. I think you’ll realize that yourself one day.’

Georgette’s mother, Sylvia Heyer, to whom Georgette dedicated Pastel. Though Georgette loved her mother, she and Sylvia had a complex and sometimes difficult relationship. (Used with permission)

The formal dedication to her mother but the personal dedication is a far more tantalising inscription to ‘Mummy’.

Norman Acre vs. Ronald Rougier

The parallels between fictional Norman Acre and real-life Ronald Rougier are many – both men are strong, good-looking and sensible, they both smoke a pipe, play rugby (rugger) and ride a motor-bike with a side-car in which Norman takes Frances to watch football matches just as Ronald took Georgette before they were married. Both are quiet men, ‘hard to ruffle’ and each is sufficient in himself. In Pastel Georgette describes Norman as:

‘Phlegmatic, stolid: these you might call him; dogged, in the style of your true Rugby football player; dull, that you might call him if you were Frances Stornaway.’

Georgette Heyer, Pastel, Longmans, 1929, p.3.

It seems unlikely that Georgette found Ronald dull, but the fictional and the real man have other things in common: both have known the woman they want to marry for several years and each is looked on with approval by the ladies’ parents, neither is ‘a hero of Asgard’ like Oliver Fayre and neither invokes in Frances or Georgette the kind of grand passion that Frances, at least, dreams of attaining. It is impossible to know whether Georgette Heyer ever dreamed of a ‘grand passion’, but Heyer’s first biographer, Jane Aiken Hodge, always believed that there had been someone in Georgette’s life whom she had passionately loved and who for some reason she could not marry. In Pastel Mrs Stornaway assumes that Frances’s feelings for Oliver are something from which she will quickly recover but Frances admits to herself that:

‘it went deeper than that. If it were no more, very pride would have nipped it in the bud. The love she felt had not died when Oliver turned to Evelyn: it consumed her still, and she knew that Oliver was the one man who could give her happiness ideal. If he had cared she would have found herself capable of treading the heights Mrs Stornaway seemed to disparage. He did not care, and Frances felt that the one chance given to each person in life had slipped by her.

Georgette Heyer, Pastel, Longmans, p.72.

A better choice

Eventually Evelyn marries Oliver and Frances settles for Norman who, like his name is very ‘normal’, but who in the end – just as Frances’s mother predicted – is a much better choice for her. Reading Pastel it is hard not to think that the novel reflects many aspects of Georgette’s own relationship and marriage.

‘He was not Romance, but he was her husband, and she did care for him. If she was not passionate that was the fault of her temperament. She thought of the man who might have meant Romance, and awaked passion obtruded for an instant. She banished it swiftly. Norman must never know that he was second-best. All thought of Oliver Fayre faded; best or second-best. Norman was her man, and she felt for him something of that protective, maternal love that decreed that nothing should worry or distress him. She got up and went to him. It was not pretence that made her eyes soft and bright with tears; passion might be lacking, but she had love for Norman. He was a dear, and so good to her, and when she saw his face set, and a little anxious, something smote her heart, and she wanted to comfort him, and to kiss him too, though not in that desperate, hard way that he seemed to require of her.

Georgette Heyer, Pastel, Longmans, 1929, p.186.

Telling too much… ?

Pastel is interesting not only for its autobiographical elements and account of middle-class life in 1920s England but also for its intimate portrait of Frances and Norman’s marriage. It is easy to think that the conversations between the newly married pair, as well as the passages of introspection in which Frances tries to work out her feelings about Norman, are a direct reflection of Georgette’s own experience of marriage to Ronald. I think that Pastel is the closest we will ever come to understanding the young, married Georgette. She is not Frances in all her incarnations, but her descriptions of Frances’s feelings – especially in in the last part of the novel – seem to align with what we know of Heyer from her early letters and from her attitude to Ronald as her first reader and counsellor. It may have been because the novel revealed too much of her life and attitudes that in the late 1930s Georgette Heyer firmly suppressed Pastel.

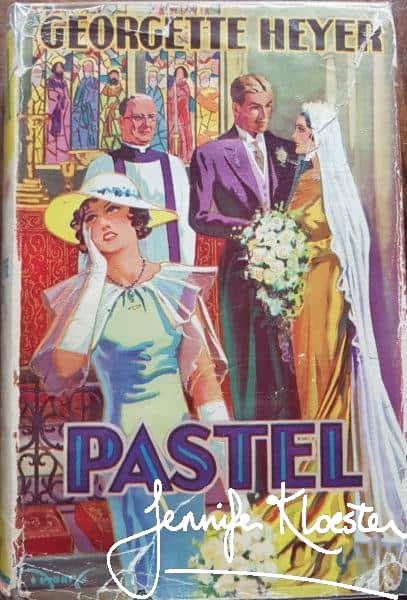

The later 1934 edition published as part of a uniform set of her modern novels with the logo: ‘A Love Story by Georgette Heyer’. She would have hated the cover and the logo.