Fun to write and fun to read

1948 proved to be another productive writing year for Georgette Heyer. She had not published a book the previous year (one of her rare years without a novel), but had written The Foundling, which appeared in April 1948. Although Ronald was encouraging her to “jack up the Regency” Georgette had her mind firmly in the period. They were now well settled in Albany in the heart of London and her books were selling well. That autumn she had two short stories – “Snowdrift” and “Full Moon” ready for November publication in The Illustrated London News and Woman’s Journal respectively. Early in October, having given up (for now) the idea of writing George, Lord Wrotham’s, story in which “Ferdy will figure largely”, she began a new Regency novel and told her publisher:

I am very busy with Arabella, who is a nice wench, and giving me a lot of fun. As for Mr Beaumaris, the fans will fall for him in rows, because he’s their favourite hero. I’ve done about 20,000 words, so it’s safe to say that the book will be in your hands well before Christmas.

Georgette Heyer to Louisa Callendar, letter, 21 October 1948.

The ease with which Heyer wrote her novels still seems extraordinary, especially given that decades later so many of her books remain as fresh and as endearing as the day they were written. As promised, just over three weeks later, Georgette finished her new novel and her publisher, Frere, wrote to “formally to acknowledge the (top, and beautifully typed) manuscript of ARABELLA.” Georgette had enjoyed writing the book with its delightful vicarage family that is a little reminiscent of Jane Austen’s family. Like the Austens, the Tallants are well-born but not rich, the father is a rector in a small country parish, both families have eight children (though the Austens had six sons whereas the Tallants have four) and both enjoy the lively and congenial life of a happy home. As Jane Aiken Hodge rightly observed, the Tallants are “one of Georgette Heyer’s rare happy families”. The novel opens with a delightful scene in the vicarage which shows Heyer utterly at home in the period and able to bring it to life with ease.

With a little realism thrown in

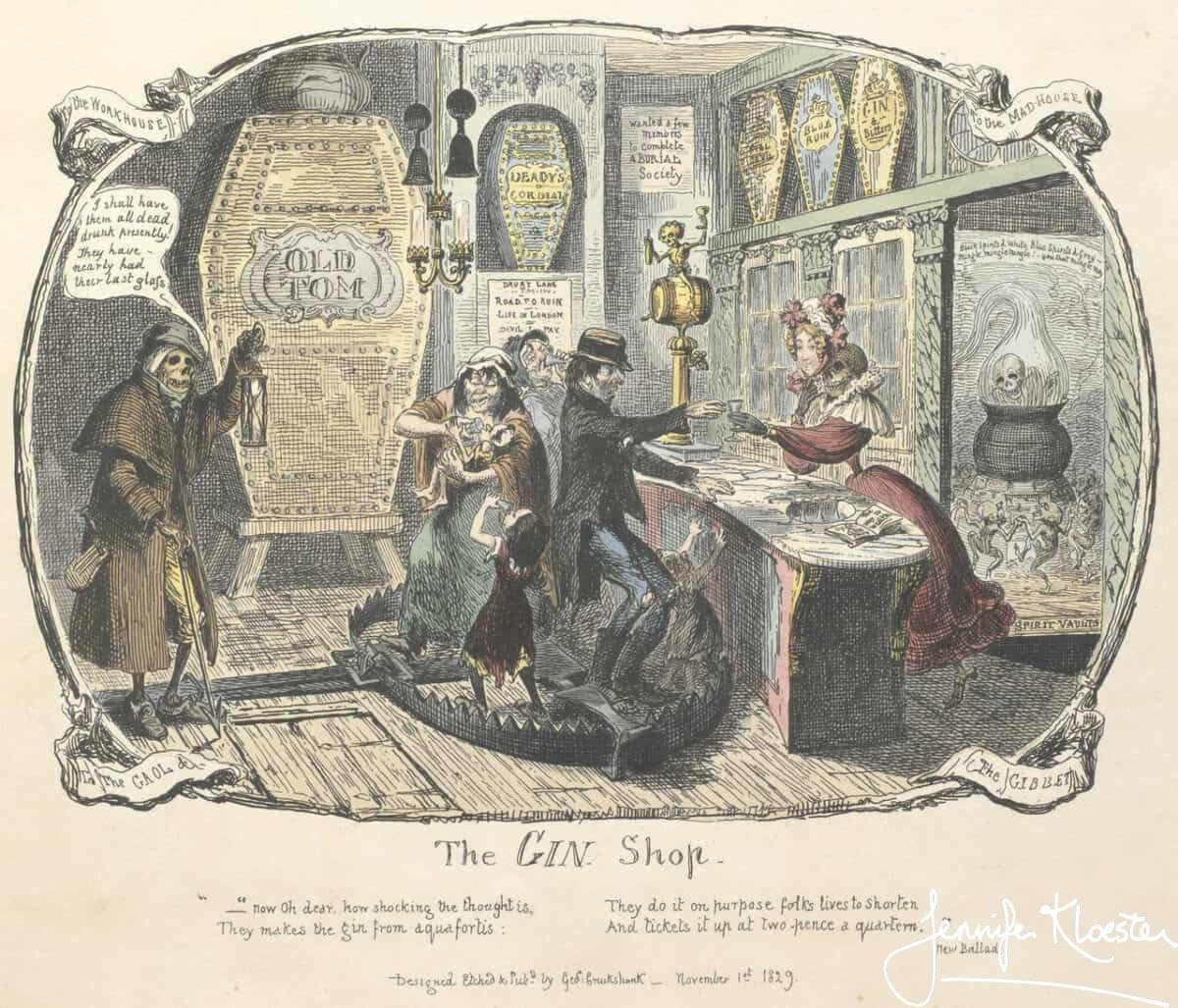

It has sometimes been said that Georgette Heyer’s novels do not reflect the seedier side of life in Regency England. This is generally true, but, while she did not often write about it, her reading of primary sources had made her aware of the harsh reality of life for many people at the time – especially those of the working and poorer classes. Occasionally Heyer’s awareness of the horrors of early nineteenth-century life for the poor comes through. In Arabella she offers the reader some genuine insight into one of the cruellest practices in British history – that of using children as chimney sweeps. Halfway through the novel a young chimney-sweep named Jemmy falls down the chimney into Arabella’s bedchamber. Aghast at the obvious abuse Jemmy has suffered at the hands of his brutal master, “Ole Grimsby” – himself one of London’s poor – Arabella sets about saving the boy from his life of misery.

This is Heyer’s most detailed account of life at the opposite end of the social spectrum. After 1666 and the Great Fire of London that so devastated the city, chimneys were designed to be narrower. Unfortunately, they still needed to be cleaned lest the build-up of soot and creosote cause a fire inside the chimney. For over two hundred years it was the job of small boys (and sometimes girls) to climb up the inside of the chimney holding a brush above their head while letting the soot fall down over them into the fireplace. Only once the chimney was cleared were they allowed to slide back down into the fireplace where their master would gather up the soot to sell to farmers for fertiliser. After the Great Fire, new chimneys were designed to be narrower – often no more than eighteen inches wide – which is why children between the ages of five and ten were deemed best for the horrific task of cleaning them. Indentured to Master Sweeps and often plucked off the street, taken from orphanages or sold by their poverty-stricken parents into slavery, these poor children were forced into the chimneys, there to endure the horrors of a difficult and often dangerous climb, encounters with rats, and lung-choking soot.

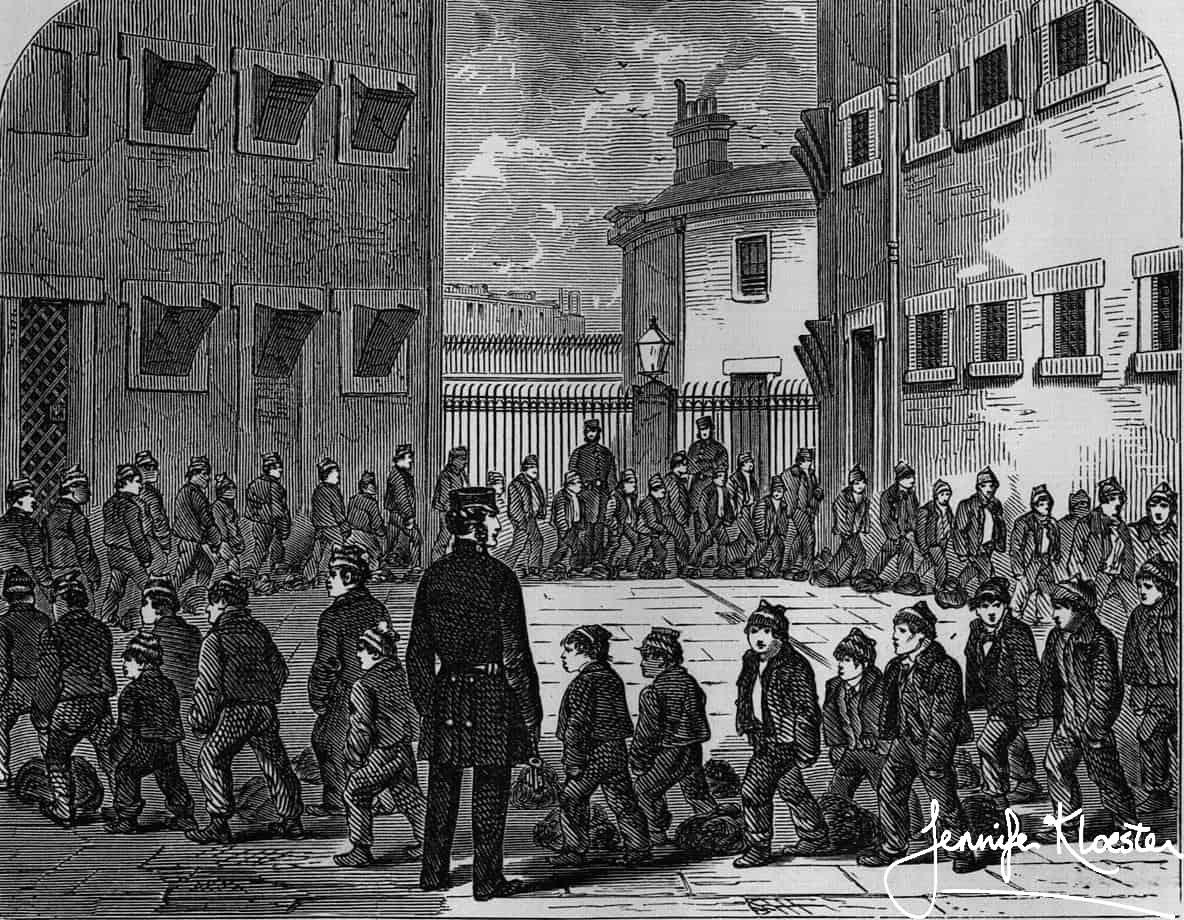

In the London Slums by Gustave Doré 1872 User:Igrimm12, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Boys exercising at Tothill Fields Prison from Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor 1851 via Wikimedia Commons

Jemmy

In Arabella Jemmy’s Master forces him to overcome his fear of “going up the chimbley” by lighting a fire beneath the six-year-old’s feet; it is from this ghastly but all-too common practice that the phrase “to light a fire under someone” originated. Young sweeps endured a life of continual suffering, with dreadful health issues including lung disease, cancer and deformities and far too many suffocated or died in the chimneys. It was eventually the death of a twelve-year-old sweep, George Brewster, who became stuck in a chimney at Fulbourn Hospital in 1875, that finally brought the heinous practice to an end. Heyer devotes almost an entire chapter to Jemmy’s story and Arabella’s passionate response to what she sees as an outrage against these unfortunate children is as welcome to the child as it is unexpected.

[Jemmy] told her, with a certain distorted pride, of the violence of one of ole Grimsby’s associates, Mr Molys, a master-sweep. Who, only a year before, had been sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for causing the death of his six-year-old slave.

“Two years!” cried Arabella, sickened by the tale of cruelty so casually unfolded. “If he had stolen a yard of silk from a mercer’s factory they would have deported him!”

Arabella, Pan edition, 1965, p.111.

Championing Jemmy against the protests of her benefactors, Arabella reveals her true nature. Her unexpected depth of character and her willingness to risk scandal and social ostracism is a turning point for the hero. But Arabella’s passionate act of kindness is not the last in the novel and Heyer takes great delight in making Mr Beaumaris the recipient of more than just a six-year-old climbing boy.

“At sight of Mr Beaumaris, seeking solace from his favourite poet in a deep winged chair by the fire, he uttered a shrill bark of delight, and reared himself up on his hind legs, his paws on Mr Beaumaris’s knees, his tail furiously wagging, and a look of beaming adoration in his eyes.”

Georgette Heyer, Arabella, Pan edition, 1965, p.140.

Ulysses

Georgette Heyer loved dogs. Her mother had always had dogs and in her youth Georgette had her own handsome Pekingese. As an adult she had had a pet Sealyham, followed by a pure-bred bull-terrier and a magnificent Irish wolfhound (as well as a Siamese cat named Puck). Dogs can be found in several Heyer novels and short stories and are much loved by fans. In The Reluctant Widow it was the glorious Bouncer – half lurcher, half mastiff – who captured readers’ hearts, and in Arabella it is the reprobate mongrel, Ulysses. Arabella saves the dog from being tortured and is determined to keep him until she realises that her hostess, Lady Bridlington, is unlikely to welcome a mongrel stray into her elegant townhouse. Once again, Arabella turns to Mr Beaumaris for aid and once again he allows her to foist the object of her compassion upon him. It is her propensity for impulsive acts of kindness that most clearly reveal Arabella’s character and it his response – albeit at times reluctant – to those that reveal so much of his.

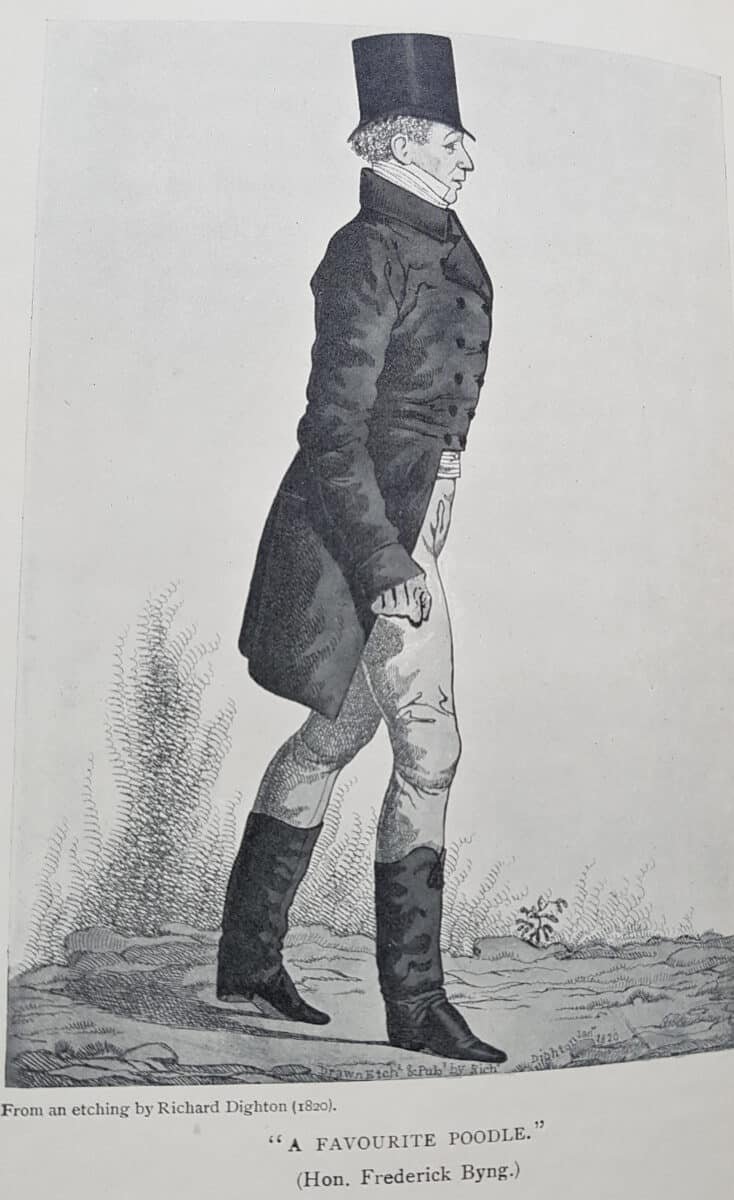

Poodle Byng

Named by the hero because his mongrel dog “seemed, on the evidence, to have led a roving life, and judging by the example we saw it must have been adventurous”, it is through Ulysses that we more fully discover Mr Beaumaris’s sense of humour, his kind heart and his deep appreciation of society’s many foibles. Ulysses is utterly unsuited to the role of gentleman’s companion and Heyer obviously derived enormous enjoyment from writing about him. Ulysses turns his fastidious master’s household upside down, winning every heart and eliciting from Mr Beaumaris his real feelings about Arabella through several very funny “conversations” between man and dog. Ulysses is such a well-drawn character that there are moments when he almost steals the spotlight from the hero and heroine. Heyer also used her adorable mongrel to bring into the story the real-life dandy, the Honourable Frederick “Poodle” Byng. She was adept at blending fiction with history and had drawn from Lewis Melville’s Beaux of the Regency a useful account of Poodle Byng which she used to highlight the absurdity of Mr Beaumaris’s acceptance of Ulysses as his personal pet. Poodle is out driving his curricle with his own “highly bred and exquisitely shaved poodle sitting up beside him” when, upon encountering Mr Beaumaris with his mongrel dog, both he and his canine companion are insulted. A lively scene follows before the two men part company and Beaumaris tells Ulysses that: “You are quite unfit for polite circles.”

Overturning romantic clichés

Towards the end of the novel, Arabella must venture into London’s slums in order to try and rescue her brother Bertram who has run away from his unpayable debts. Escorted to a rundown inn in Tothill Fields, there she meets a couple of prostitutes, one of whom, Leaky Peg, has helped Bertram to survive after he has almost drunk himself to death over a gambling debt he cannot pay. Arabella’s gratitude is generous and sincere and, although it is her first experience in such a setting or with such women, Heyer uses the scene to depict both Arabella and Leaky Peg as worthy people whose class differences do not prevent either woman’s innate humanity. There is nuance here and, despite its comic intentions, a close reading shows how deft Heyer was at creating three-dimensional minor characters. She was also a master of plot and the final scenes of Arabella reflect her love of turning romantic clichés on their head. The story moves from the backslums of Tothill Fields south-west of St James’s Park to Wimbledon and a grand unknown house. Arabella has asked Mr Beaumaris to elope with her so that she, as his wife, might ask him to give her the money to pay Bertram’s debts, but instead of heading north to the Scottish border, she finds herself being led into an unknown house:

“Arabella stood turned to stone as all the implications of her surroundings burst upon her. Mr Beaumaris’s soothing assurance to her that they would not elope now became invested with the most sinister significance”

Georgette Heyer, Arabella, Pan Edition, 1965, p.241.

In many romance novels of the time (and both earlier and later) this moment might easily have meant rape or the threat of rape. Heyer knows this all too well, but just as she did in Devil’s Cub, here too she turns the scene on its head, using the benign device of a glass of milk to assure Arabella that Mr Beaumaris’s intentions are neither sinister nor a threat:

“The promise of a glass of hot milk, which hardly seemed to be in keeping with the hideous vision of seduction and rape which had leapt to her mind, a little reassured Arabella.”

Georgette Heyer, Arabella, Pan Edition, 1965, p.241

For all its more realistic moments with Jemmy, Ulysses, Leaky Peg and Quartern Sue, Arabella remains a delicious confection to delight readers of all ages. This is a Cinderella story with an endearing, impulsive and passionate heroine, who finds in Mr Beaumaris an unexpected Prince Charming – a man who can play at Lottery Tickets with her mama and siblings but who can also sit for hours discussing ancient texts with her scholarly father. There is more to both of these characters than meets the eye and, as in one of Heyer’s favourite novels, Pride and Prejudice, both must come to realise that their first impressions of each other are wrong.

The 1965 Pan edition of Arabella.

The 1971 Pan edition of Arabella

“An exemplary piece of escapist literature”

“Miss Heyer seems to have hit upon a method of writing period novels that is much more successful than most, although limited in its possibilities of application. With pleasant directness, she adopts the most graceful literary mode of the period she has chosen to write about. The era she has selected in this case is that of Jane Austen, and her genteel Regency settings and people are good enough to fool any but the most puristic Janeite. The plot deals with a poor country vicar’s daughter who snags a renowned London dandy, an event that is annotated with sufficient Georgian embellishment and wit to provide an exemplary piece of escapist literature.”

The New Yorker, 28 May 1949, p.96.

1 thought on “Arabella – “who is a nice wench and giving me a lot of fun””

Was Georgette Heyer acquainted with either Benjamin Britten or Eric Crozier? It seems a bizarre coincidence that “Arabella” appeared the same year that Britten’s “Let’s Make an Opera” (incorporating “The Little Sweep”) was produced. Crozier’s libretto mirrors Heyer’s story to a remarkable degree. Even the names of the sweeps–Jemmy and Sammy–are similar! Of course Britten’s opera was praised for its social consciousness while Heyer’s book was denigrated for its escapism. I attended a local performance of “Let’s Make an Opera” many years ago, enjoyed it immensely (as I do Georgette’s work), and was forced to laugh at a priceless moment in the proceedings when the audience had to sing one of the choruses: a certain audience member began to sing ahead of everyone else–completely off in their timing. It turned out to be a well-known classically trained singer!