A watershed year

!942 was a watershed year for Georgette Heyer. In May she finished writing Penhallow, the novel she believed was ‘a bit of a tour-de-force‘ and in November she and Ronald moved into a set of chambers in Albany in central London. Albany would prove to be a very good move for Heyer, for over the next twenty-four years she would write some of her finest novels there. Penhallow, however, would be the greatest personal disappointment of her writing life. Published in October 1942, it sold out its first print run of 12,500 copies but it did not win her the rave reviews Georgette had been hoping for. It is possible that her disillusionment over Penhallow was one of the reasons why she produced no book in 1943 – a rare absence that had happened only twice before in 1924 and 1927. These were also the War years and challenging times for the British. Although Georgette was stoical by nature something kept her from her writing for well over a year after she had finished Penhallow.

Very few letters extant

1943 was also a year for which there are very few letters extant. There are only nine letters for the entire year, with one written in January and the remaining eight written from August onwards – six of them to her agent and two to her friend and publisher, A.S. Frere of Heinemann. Several of the letters are written from the St Enodoc Hotel in Wadebridge, Cornwall, where Georgette and Ronald and their eleven-year-old son, Richard, were spending several relaxing weeks and where Georgette was apparently convalescing after some sort of illness. The only clue to her long hiatus from her usual energetic writing lies in a postcard written from Cornwall to her agent, Leonard Moore, which ends: ‘Health better, pen still idle’. She also wrote a cheerful letter to Frere which included a paragraph in typical humorously self-deprecating Heyer-style which reflected her more hopeful state of mind regarding books she might soon write:

Are you at Cape Wrath, & is it fun? With luck, I shall write a thriller for Uncle Percy [her Hodder & Stoughton publisher] while I’m here, & then I can get down to a book for you. It might be Wellington, but quite easily not. Maybe I’ll make some easy money with a frippery romance. You needn’t put on your despising-face, either, because if I do prostitute my deathless art you’ll do very well out of it.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 3 August 1943, written from the St Enodoc Hotel, Wadebridge, Cornwall.

It is not known exactly what Georgette meant by ‘the Wellington book’ but for she had a long-held ambition to write a serious biography and after her work on An Infamous Army and The Spanish Bride she may have had the Duke of Wellington in her mind as a likely subject. Whatever her idea, she never did write a biography. The closest she ever came was her fictional posthumous novel, My Lord John, about the John of Lancaster, which she never finished.

Illness or disappointment or something else?

It is possible that earlier in the year Georgette had succumbed to a severe illness or suffered one of her ‘nervous breakdowns. It is also possible that in the months following the publication of Penhallow (October 1942) that her disappointment over the novel’s reception had badly affected her. She had had high hopes for Penhallow, believing her agent and publisher who had each told her it would be a suces fou – an extraordinary success. Unfortunately, although the book did well and earned good reviews, Georgette’s vision of accolades and recognition had not been realised. Whether it was her disappointment, a serious illness or something else that prevented her from writing we may never know. What is certain is that when she finally did begin writing again, it was to be a book that would forever change the course of Georgette Heyer’s career.

Shakespeare and Cophetua

Within six weeks of her return from Cornwall, Georgette had written 55,000 words of her new novel. She had dispensed with the idea of writing a thriller for Hodder & Stoughton and begun a vivacious historical romance. This would be her 32nd novel but only her fifth book set in the true English Regency – that period between 1811 and 1820 when George III had been declared mad and his son, George, Prince of Wales was appointed Regent to rule in his father’s stead. On 12 November Georgette told her agent that she had written about half the book and gleefully explained that

It is very lively indeed – a laugh on every page, & people ought to lap it up. I have a new sort of character in George, Lord Wrotham, who amuses me tremendously. He is a beautiful & turbulent young man, always trying to call his friends out to fight duels, & never succeeding. He’s in love in a very romantic & despairing way with the Beauty, & I’ve got him well & truly embroiled in the Heroine’s affairs too.

Georgette Heyer to L.P. Moore, letter, 12 November 1943.

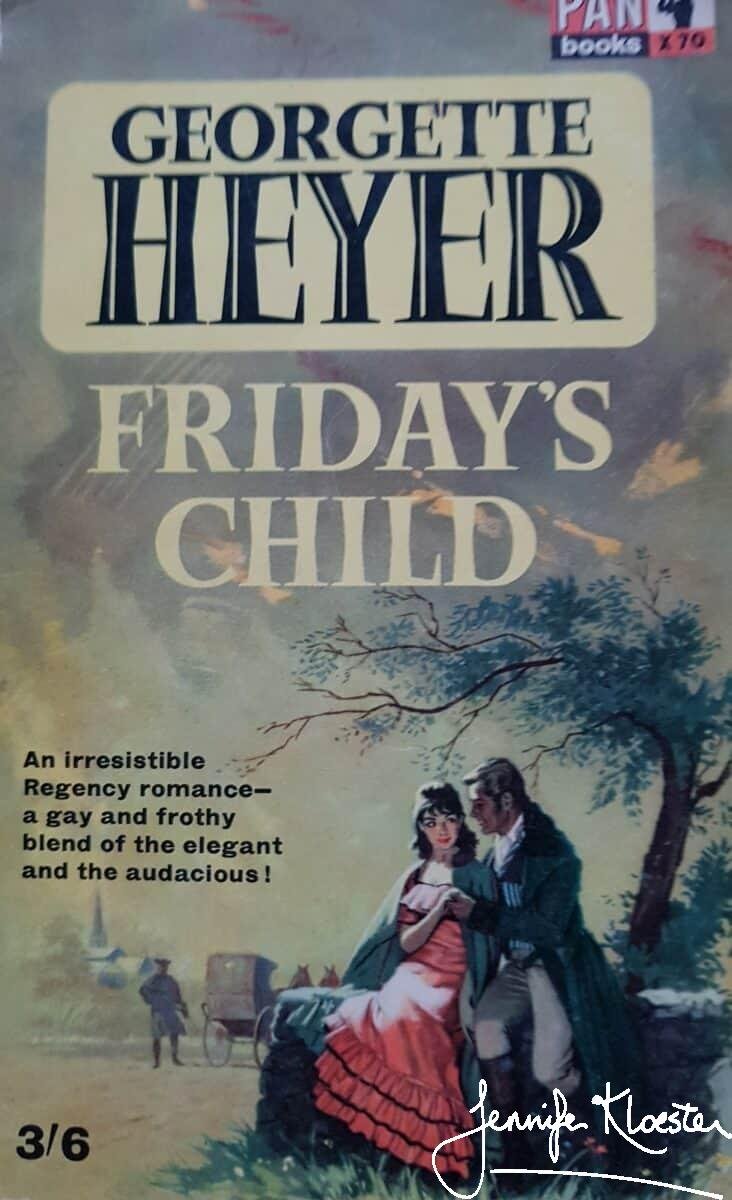

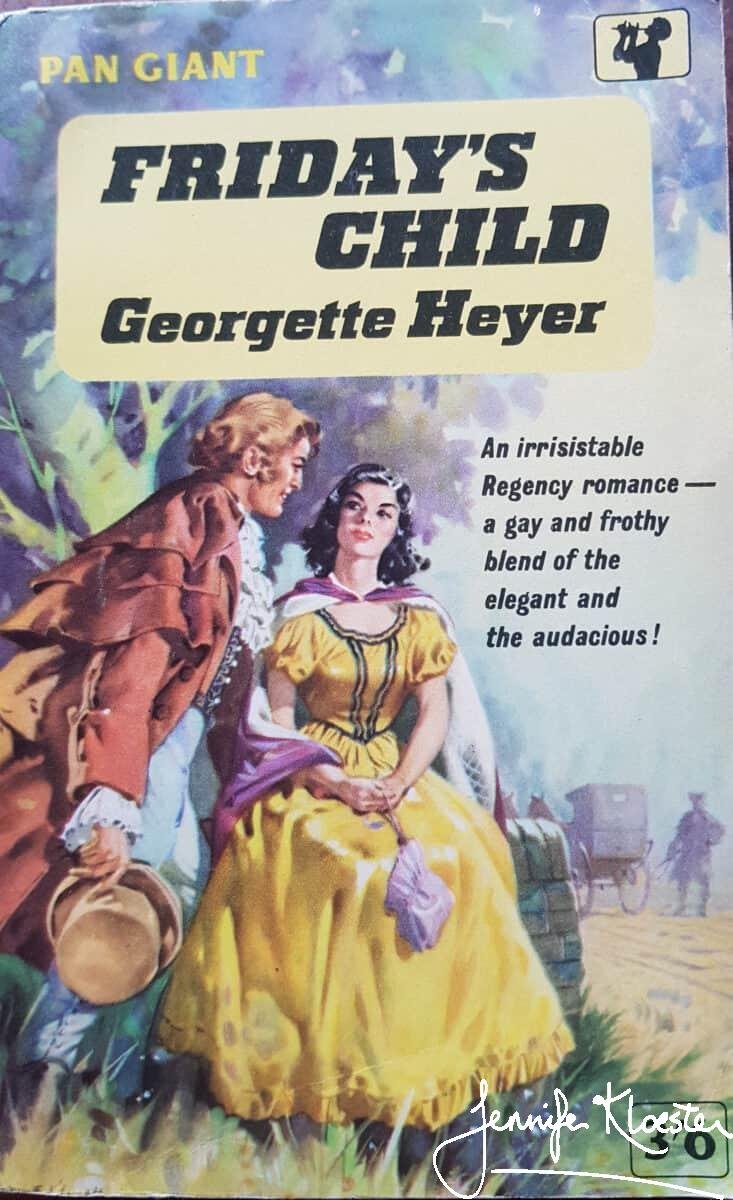

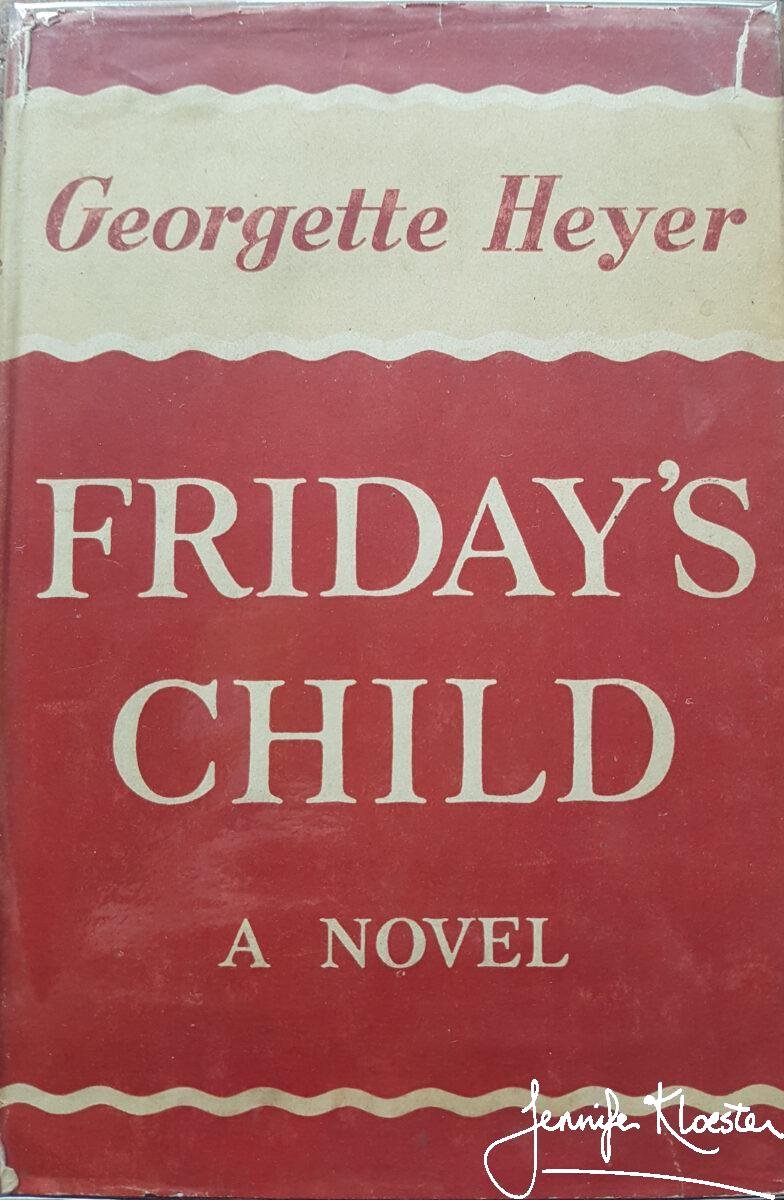

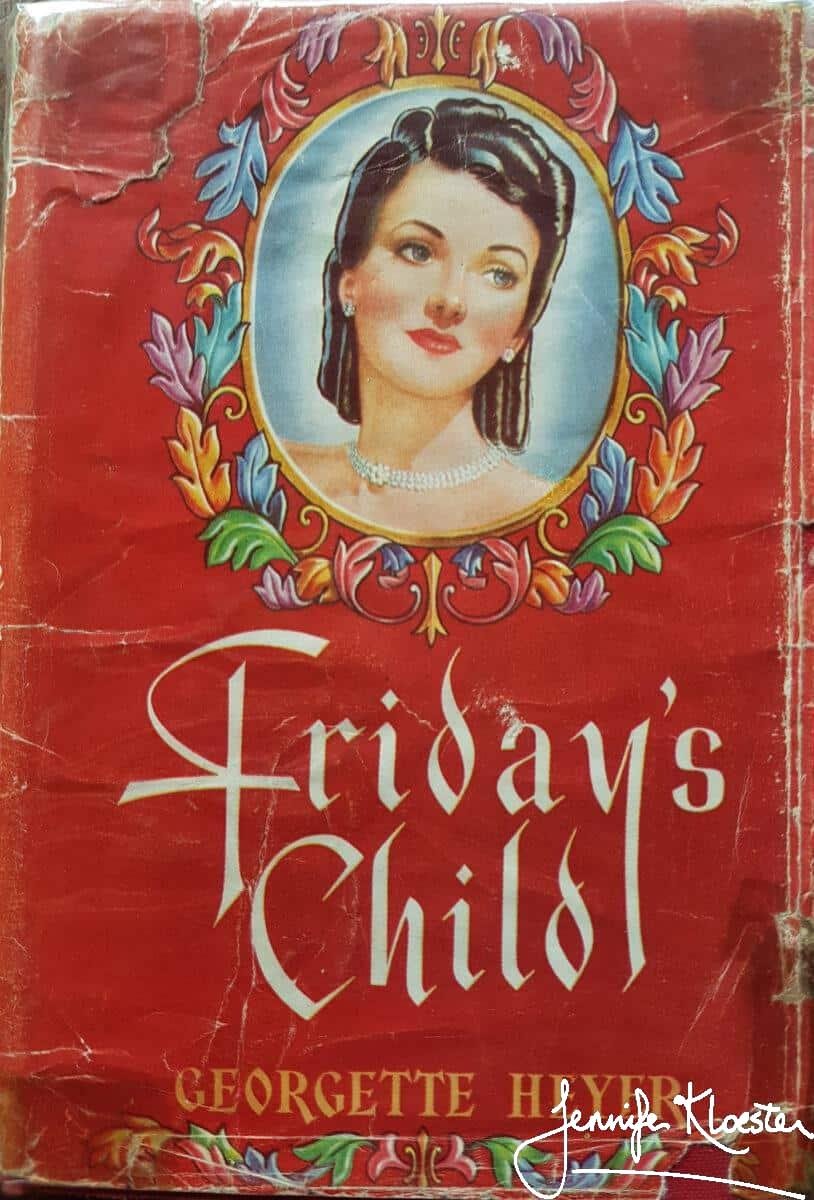

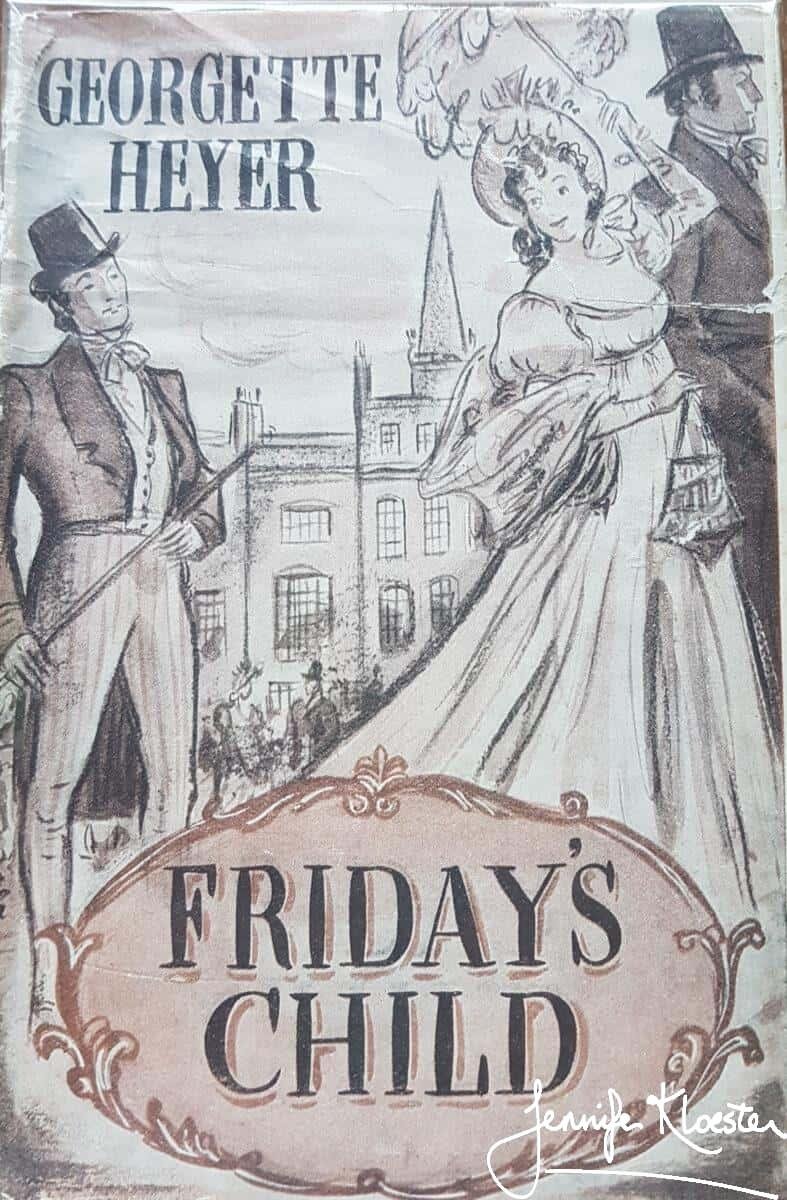

Georgette was once again writing at top speed and with all of her usual verve and enthusiasm. At first, she thought of calling the new book Cophetua, after the 16th century ballad about King Cophetua and the beggar-maid. The word “Cophetua” had become shorthand for a man who falls in love with a woman and instantly marries her. The story would have been familiar to anyone brought up on Shakespeare as Heyer was, for the Bard alludes to the tale in several of his plays. Heyer enjoyed using Shakespeare as a source when naming her novels. Unfortunately, neither her publisher nor her agent thought Cophetua a ‘selling title’, so Heyer offered them an alternative: Friday’s Child. She had been a little “dubious about Friday’s Child‘, thinking it too similar to Faro’s Daughter, but both Frere and Moore were enthusiastic. That was good enough for Georgette who told them: “since you both like the title, & it is certainly apt, I’ve decided to use it.'”

Georgette’s personal favourite

Friday’s Child was Georgette Heyer’s personal favourite among her many novels. She always said it was because of Ferdy Fakenham, that slightly dim-witted, but very funny, foil to the young and impetuous hero, Lord Sheringham. Ferdy is definitely a stand-out in the novel, not only for his occasional lapses into (for him) deep thinking, but also for his glorious take on Nemesis, the Goddess of Retribution. Heyer’s running joke in the novel has become a byword among Heyer fans and just the mention of the name is enough to provoke laughter among knowing readers. Ferdy is joined in this witty, light-hearted story by his friends: the impulsive hero, Sherry (Lord Sheringham), charming Gil Ringwood, and the handsome, hot-blooded Byronic alpha male, George, Lord Wrotham, while the endearing heroine is the appropriately named “Hero”. She is the “Friday’s Child” of the story and a joy to read. Smitten with Sherry and married on a whim, Hero makes her debut into Polite Society with a glorious naiveté that has many unexpected consequences for her young and irresponsible husband. Heyer’s genius for comedy and her mastery of period detail and language is evident throughout as she takes her unlikely couple on a whirlwind ride from London to Bath in a story replete with wit and humour.

A dozen excerpts

As was often her way when she was excited about a book she was writing, Heyer took the time to write out a dozen excerpts from her work-in-progress for her agent. In the case of Friday’s Child the hand-written excerpt ran to three full pages before Heyer ended with the hope that Moore would find the contents amusing and a brief synopsis of what remained to be written:

Well, that should give you a very fair idea of my quality in this book! I am now going to deal with Sir Montague Revesby’s bastard-infant, & the Betrayed Village Maiden. This little affair, & my incredible heroine’s part in it, effectually puts a stopper on Sherry’s disastrous friendship with Revesby. So it is a Good Thing about the Baby. After that, we shall work up to the final Quarrel between this peculiar couple, leading up to the heroine’s flight to Mr Ringwood – complete with ormolu clock, & canary in a cage – her sojourn at Bath with Mr Ringwood’s grandmother, the arrival in Bath of George, Sherry, the Beauty, & Sir Montague, & then the final mix-up, in which a nice man called Jasper Tarleton is implicated, Sir Montagu does a hurried exit on finding that George is out for his blood (you’ve gathered that George is a crack-shot?), Isabella at last consents to marry George, & Sherry discovers he’s been in love with his own wife for months. Voilà!

It was a joyful letter about what was to be a joyful book and Friday’s Child would mark the birth of the genre that Georgette Heyer created – the most popular historical novel genre that would become known around the world as ‘the Regency’.