Georgette and the “Great Jane”

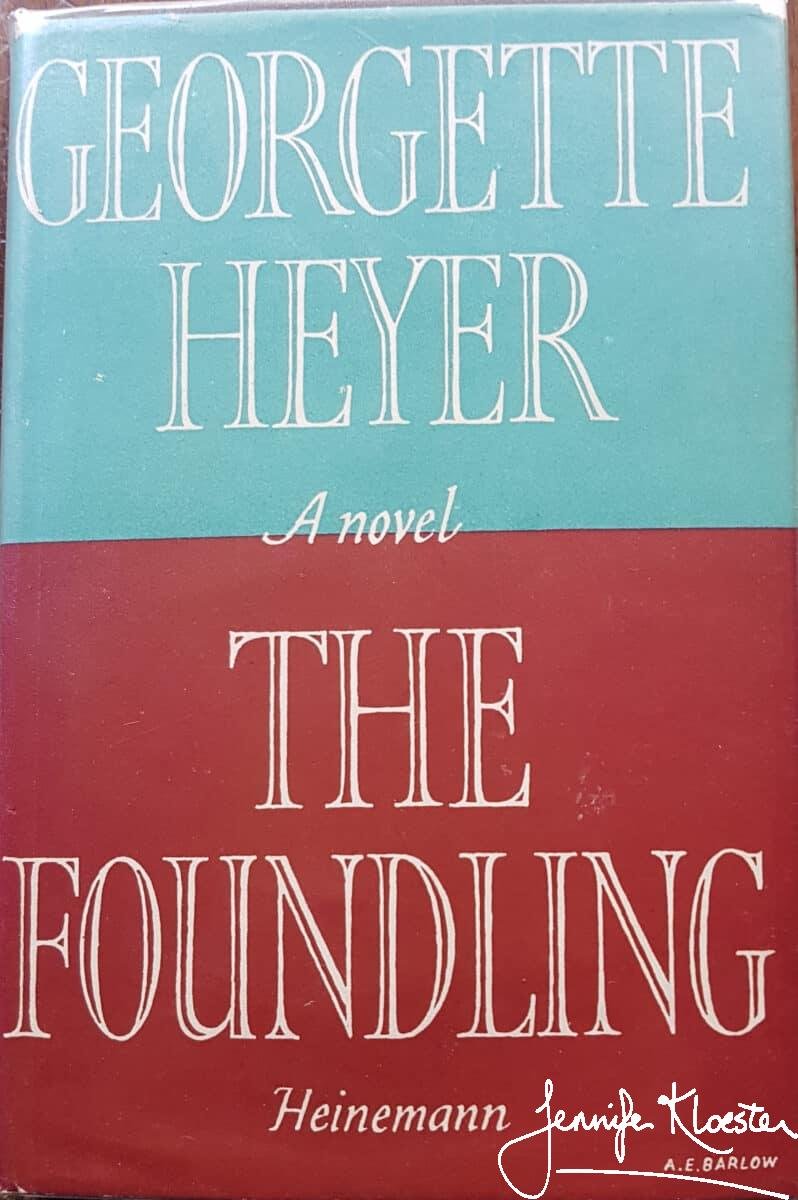

Jane Austen was Georgette Heyer’s favourite author and Austen’s six novels her choice of literature should she ever have been marooned on a desert island. A close reading of Heyer’s own novels reveals many moments where she pays homage to the “Great Jane” through her use of Austenesque humour, witty dialogue, town and country settings and characters whose personality and behaviour frequently show them to be literary descendants of some of Austen’s greatest creations. Not that Heyer copies Austen – her regard for the creator of Emma and Pride and Prejudice was too great for that – but she does draw inspiration from her literary idol and there are many instances where Heyer borrows from Austen an encounter, a minor theme, a character, a setting, a phrase or piece of dialogue as a starting point for a scene in her novels. In 1947, when Georgette began writing a new Regency novel to be called The Foundling, one suspects she had been reading Jane Austen again and very likely Emma.

A young and foolish foundling

It is in Emma that the eponymous heroine befriends the young and foolish foundling, Harriet Smith, and sets about directing her life. Harriet Smith is pretty and naive and in love with the prosperous young farmer, Robert Martin, who has offered her marriage. However, Emma disapproves of the match and encourages Harriet to refuse Martin. Instead, Emma engages to find Harriet a “more suitable” husband in the new clergyman, Mr Elton. Emma is the story of a bored young woman shackled by gentle domestic tyranny who seeks to alleviate her boredom by match-making and managing other people’s lives. The Foundling is the story of a bored young man shackled by gentle domestic tyranny who seeks to alleviate his boredom by escaping from other people’s match-making and their well-meant management of his life. In both novels the foundling is the device each author uses to teach her main character some much-needed life lessons.

Of course, as she would have been the first to admit, Georgette Heyer is not Jane Austen. Rather than imitate her favourite author, Georgette repeatedly pays homage to Austen by frequently taking an Austen element as a starting point and then taking her story in a completely different direction. The Foundling is a sparkling example of Heyer’s determination never to attempt to imitate the author she admired above all others. A few examples: where Emma’s journey of self-discovery takes place entirely within the confines of her village, Gilly’s journey requires him to leave his cloistered home and go out into the world; in Emma the charming scoundrel, Frank Churchill, is hidden in plain sight, whereas in The Foundling, the charming scoundrel, Liversedge, is instantly obvious; neither Emma nor Gilly perceive their ideal partner at first – though both Mr Knightley and Harriet are right in front of them. While each eventually discovers their true feelings, Emma’s epiphany comes from an external threat in the form of Harriet’s purported love for Mr Knightley, while Gilly’s comes from within and is the result of having finally learned who he is and what he wants his life to be like. There are many other Austenesque moments in The Foundling, not least in the style of the novel. As the reviewer from the TLS remarked:

‘There are frequent echoes of Jane Austen, for instance, in such a sentence as: “She will always be silly, but he appears to have considerable constancy, and we must hope that he will always be fond.”

“Period Pieces”, The Times Literary Supplement, 24 April 1948, p.229.

“A really flowering success”

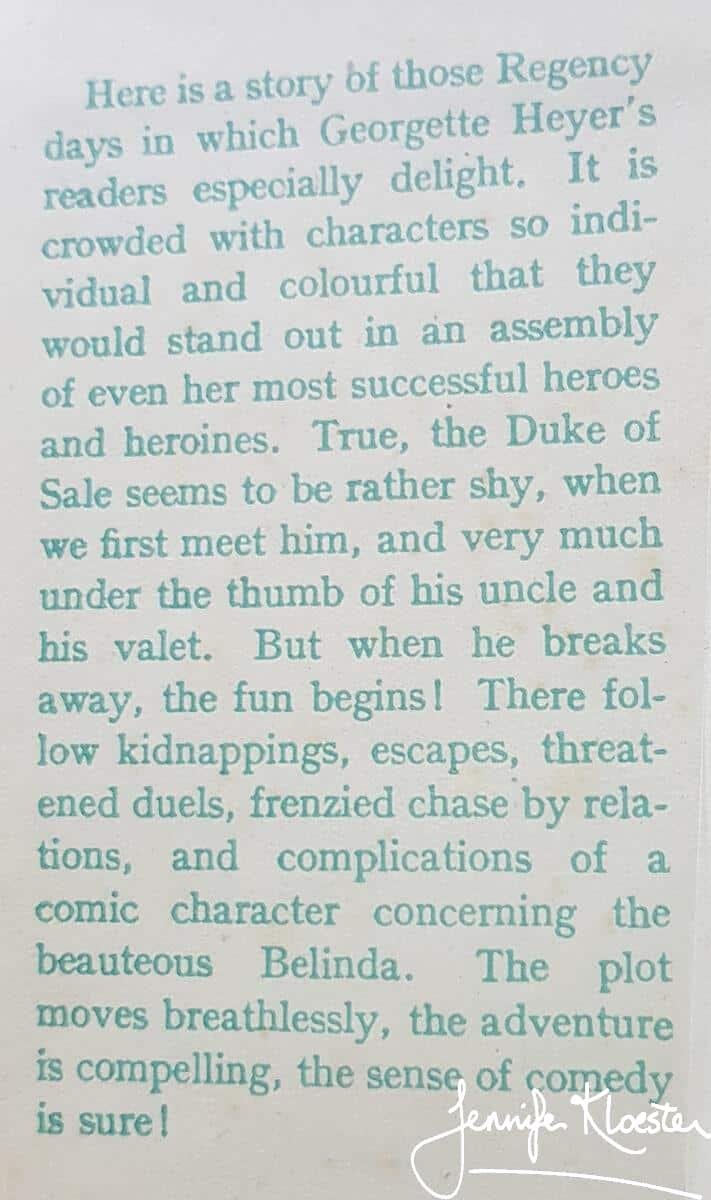

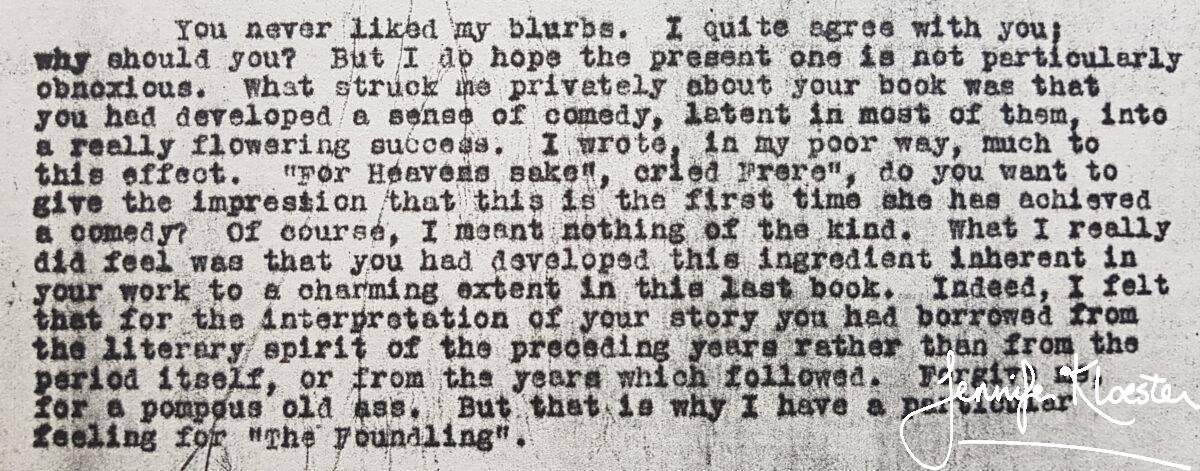

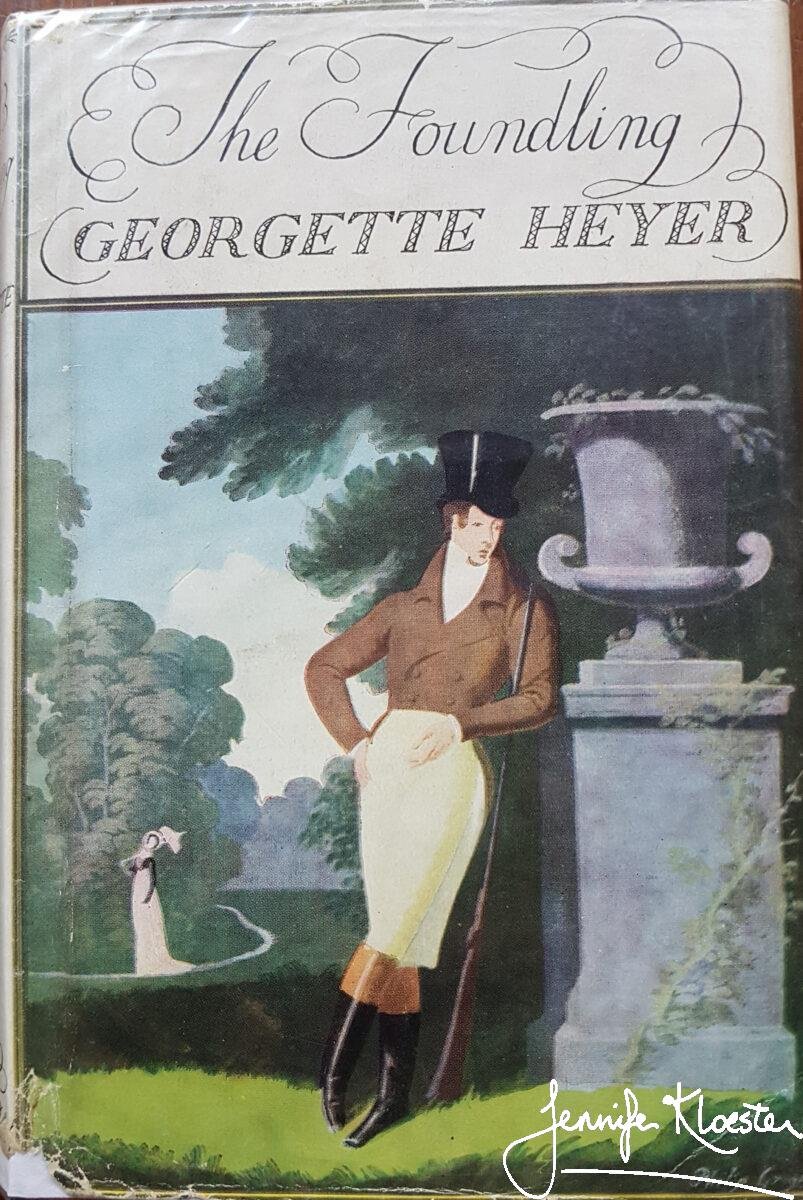

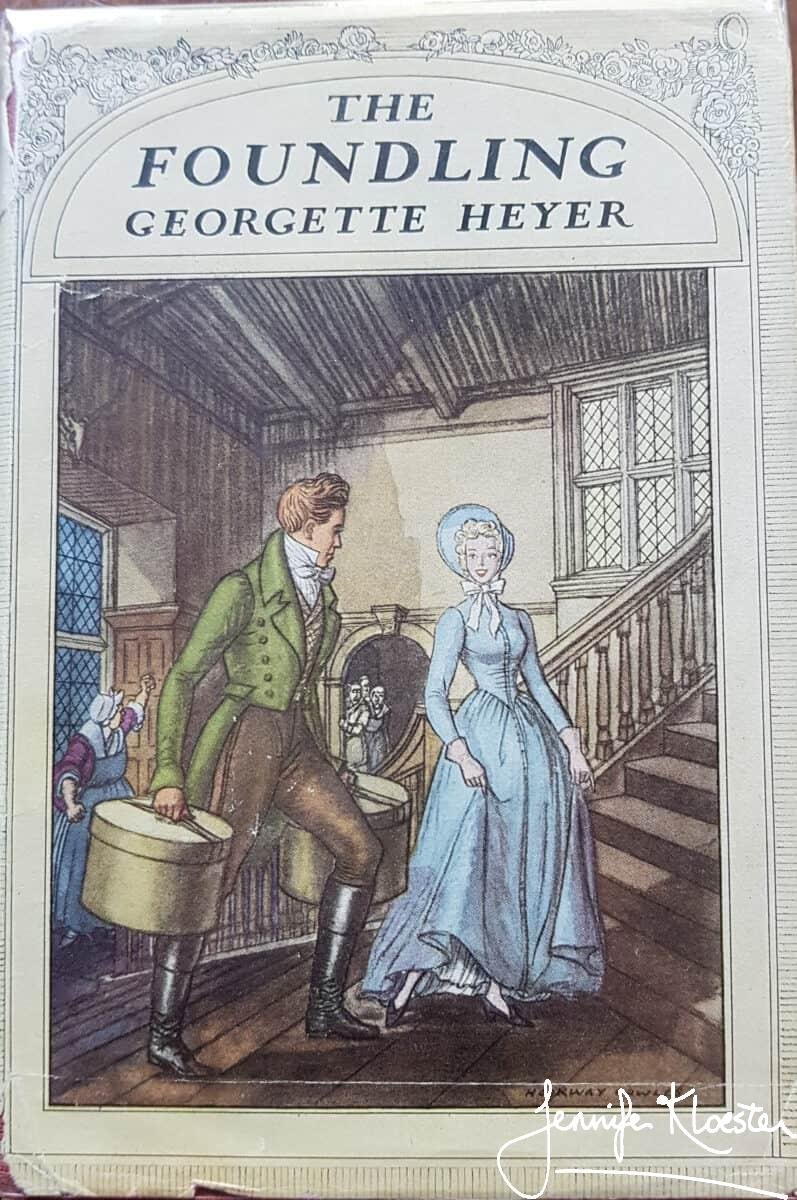

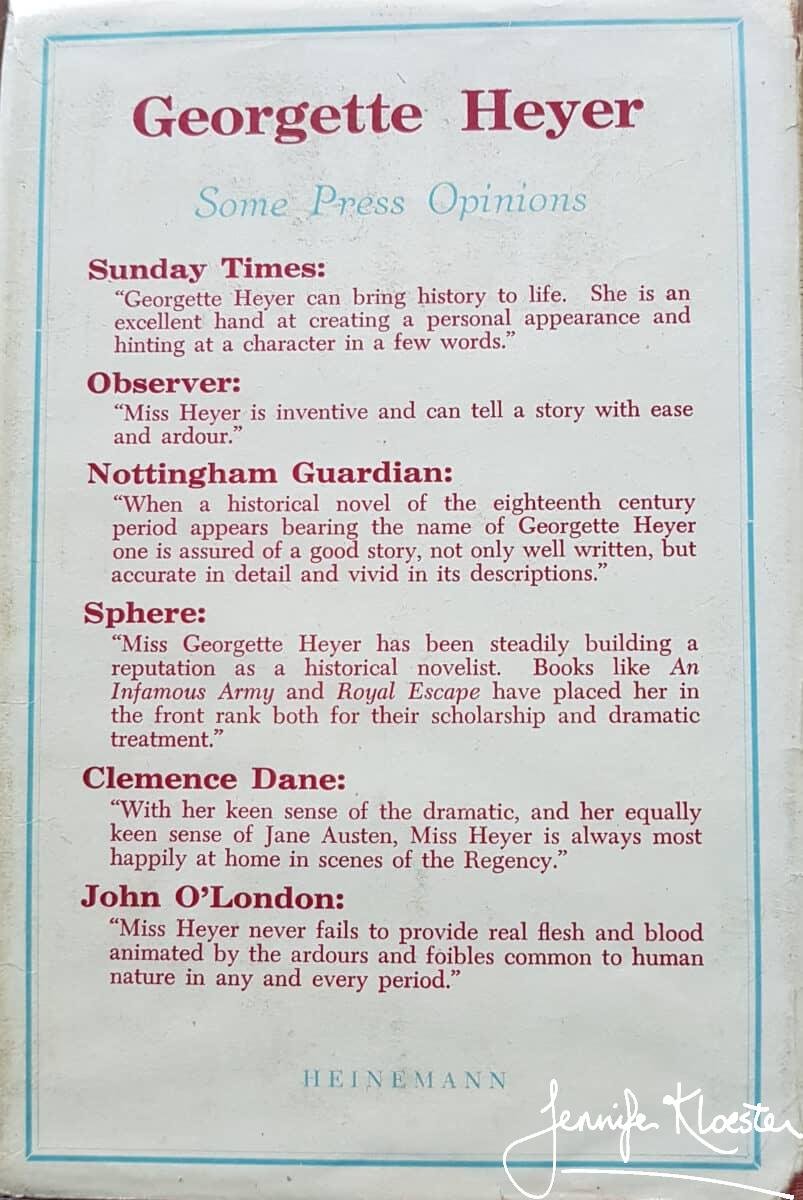

On 1 April 1948, the head of the Editorial Department at Heinemann, Arnold Gyde, wrote to Georgette to wish her luck for the publication of The Foundling on April 12th. In a kind and empathetic letter, Gyde also told her that they had sent out ‘the largest list of review copies’ for her books and that Ralph Strauss of The Sunday Times had grabbed his copy of The Foundling with ‘avidity’. Gyde told her how much he had enjoyed the novel and how he felt that Georgette had ‘developed a sense of comedy’ into a ‘really flowering success’. It was an astute observation for The Foundling is replete with comic moments.

‘Miss Heyer’s talent is elegant farce and she knows her craft well. It is, without apologies, a lighter-than-air craft.’

Richard Match, “Metamorphosis of the Duke of Sale”, The New York Times Book Review, 21 March 1948, p.20.

Georgette was pleased with the novel and delighted to learn that Woman’s Journal had offered £1000 for the serial rights. This was good money and although she was no fan of the editor, the autocratic Dorothy Sutherland, Georgette knew it could only help her sales to be published in the prestigious magazine. Her antipathy towards Miss Sutherland – brought about by the editor’s repeated alteration of her book titles – for example, Regency Buck to Gay Adventure – is reflected in her comments to her young Australian fan, Rosemary White. Georgette wrote to Rosemary and receiving another food parcel from Australia. Appreciative of the gesture (though not needing the food, for despite rationing, Georgette could still shop for food at Fortnum & Mason’s on the other side of Piccadilly), Georgette wrote to ask Rosemary:

And what, pray, can I possibly send you in return, from this impoverished island? I know you would like a new book by Me, but I can’t send you that, because it won’t appear until March. It is coming out in serial form in Woman’s Journal – one of those horrid monthly magazines which request you to “turn to page 175” after the first few paragraphs. For reasons which I don’t pretend to fathom, the editor has altered my title, which is “The Foundling”, to “His Grace, the Duke of Sale.” Apart from the really awful snob-value of this, I believe the dictum laid down by my son at the age of twelve is correct: A Five-Word Title Won’t Do!

Georgette Heyer to Rosemary White, letter, 27 October 1947.

It is interesting to note that Georgette, so often deemed a dreadful snob herself, should have marked the snobbery inherent in the revised title of her novel. She was not always a snob, as evidenced by her long friendship with Isabella Banton, her former landlady in Hove, but like most people, she had inherent biases and an unfortunate habit of labelling people en masse, such as the French, the Irish, Jews or Americans, whereas in a one-on-one situation her attitude was often very different. Being intensely shy, Georgette was slow to make friends, but if a person was intelligent (not necessarily educated) and could hold a conversation, over time, she would warm to them and a solid friendship might form, regardless of their background. She did not have a large circle of friends but those she did have, loved and admired her in spite of her biases and forthright (sometimes offensive) opinions. Those opinions often changed over time as she learned and grew and this evolution is also reflected in her novels.

The Duke of Sale – “I rather love him myself”

Although Georgette Heyer is famous for describing her heroes as either “Mark I: the brusque, savage sort with a foul temper and a Know-All” or “Mark II: enigmatic or supercilious and suave, well-dressed, rich, and a famous whip,” she did, in fact, devise a number of different kinds of heroes that were neither Mark I nor Mark II. One of these is The Foundling‘s hero, the young and untried, “Most Noble Adolphus Gillespie Vernon Ware, seventh Duke of Sale” – also known to his friends and intimates as “Gilly”. Heyer enjoyed writing this new kind of hero and told Rosemary White that she hoped she would like him:

“He isn’t tall, or handsome, or dominant, but I rather love him myself.'”

There is a lot to like about Gilly as he tries to sort out the tangled affairs of a lively and memorable cast of characters. It says much for Heyer’s skill that she was able to so seamlessly weave into the story such a diverse and mismatched set of people. Among these are the foolish but beautiful Belinda (the foundling); young Tom Mamble, the wealthy ironmonger’s son; Lady Harriet Presteigne, Gilly’s shy and gentle betrothed; his big cousin Gideon (whom every reader wishes had his own novel); the autocratic Lord Lionel Ware; the feckless and impulsive Lord Gaywood, Harriet’s brother; and, perhaps most impressive of all, the villainous Swithin Liversedge who, despite his willingness to murder the young Duke, proves astonishingly endearing! Amongst this robust cast of characters the Duke must hold his own. He proves to be a kind, caring and gentle hero (neither Mark I or Mark II) whose innate good manners carry him through many difficult and often hilarious situations.

Georgette Heyer to Rosemary White, letter, 27 October 1947.

Harriet and Belinda

‘Unless I do something about Harriet, this will be a novel without a heroine, for no one could call the ravishing Belinda a heroine. And whether I shall let it stand as it is – a leisurely, long book – or whether I shall ruthlessly cut & re-write I know not.

Georgette Heyer to A.S. Frere, letter, 1 May 1947.

In Heyer’s new novel, the pretty, naive foundling is Belinda. She is wonderfully foolish and disastrously innocent. Always ready to go off with any gentleman who will promise her a purple silk gown, she causes Gilly endless problems. Like Austen’s Emma, Heyer’s foundling is in love with a farmer but, after leaving his home, has no idea how to find him again. As her protector, Gilly, (unlike Emma), has no wish to keep Belinda from marrying her farmer. Instead, he does all in his power to reunite her with Jasper Mudgley. The scene in the novel where Belinda is reunited with her lost suitor, “his sleeves rolled up, and his shirt open to reveal the tanned, sturdy column of his throat” is truly memorable and Heyer perfectly describes its effect on Lady Harriet:

” not even Harriet, with twenty years of strict training behind her, could wonder that Belinda no sooner saw him than she gave a little scream of joy, and, without waiting for the steps of the chaise to be let down tumbled headlong into his arms.”

Georgette Heyer, The Foundling, Pan edition, 1967, p.330.

Harriet is one of Heyer’s unexpected heroines. Despite being absent for most of the middle part of the book she is crucial to the plot. It is in his relationship with Harriet that the reader clearly sees how much both she and the Duke have changed. Both shy and uncertain at the beginning when Gilly must ask Harriet to marry him, in the final chapters he is a different being. Harriet, too, has evolved and some of their final scenes together are among Heyer’s most poignant and touching.

Sir Timothy and Gideon

Among Georgette Heyer’s many talents was her remarkable ability to create a fully-formed character in a few lines, a paragraph or half a page. The Foundling has several of these including Lord Lionel’s “old crony”, the cynical Timothy Wainfleet. He appears en scene for just on two pages but we know him intimately almost at once:

“I wonder why I did not tell my man to deny me?’ mused Sir Timothy. “I never listen to gossip, you know. Really, I do not think I can assist you!”

“You listen to nothing else!” retorted Lord Lionel.

Sir Timothy looked at him in melancholy wonder. “I suppose I must have liked you once,” he said plaintively. “I like very few people nowadays; in fact, the number of persons whom I cordially dislike increases almost hourly.”

Georgette Heyer, The Foundling, Pan edition, 1967, p.184.

One of Heyer’s most popular creations is a man many readers devoutly wish had had his own book. Gideon Ware is the Duke of Sale’s “big cousin”. Gilly’s senior by four years Gideon is a captain in the King’s Life Guards and the only one among the young Duke’s many relatives who does not try to cosset or control him. Gideon is an enigmatic character – one of Heyer’s perceptive men with a lazy smile and way of talking. Very little perturbs him until he comes face-to-face with the rascal, Liversedge, who has kidnapped his cousin. Gideon is all strength of mind and body and stands in useful contrast ot his much smaller, less confident ducal cousin. They are great friends, however, and it is a measure of how much Gilly has learned and grown in confidence as a result of his adventures that, by the end of the novel, he is able to demand, “Gideon, will you have the goodness to allow me to manage my own affairs?”

Heyer had a deep appreciation of Austen’s wit and wisdom and she more than once acknowledged her indebtedness to both Austen’s novels and her letters as sources of language and information about the period. But Heyer drew much more than this from Austen. Although the two writers occupy different spheres in the literary canon, for any reader familiar with both there is much enjoyment to be derived from the clearly Austenesque aspects of The Foundling and many of Georgette Heyer’s other Regency novels.

1 thought on “The Foundling – Inspired by Austen”

One of my all time favourites! Thank you for a perceptive and informative article – now I have to go and re-read The Foundling.